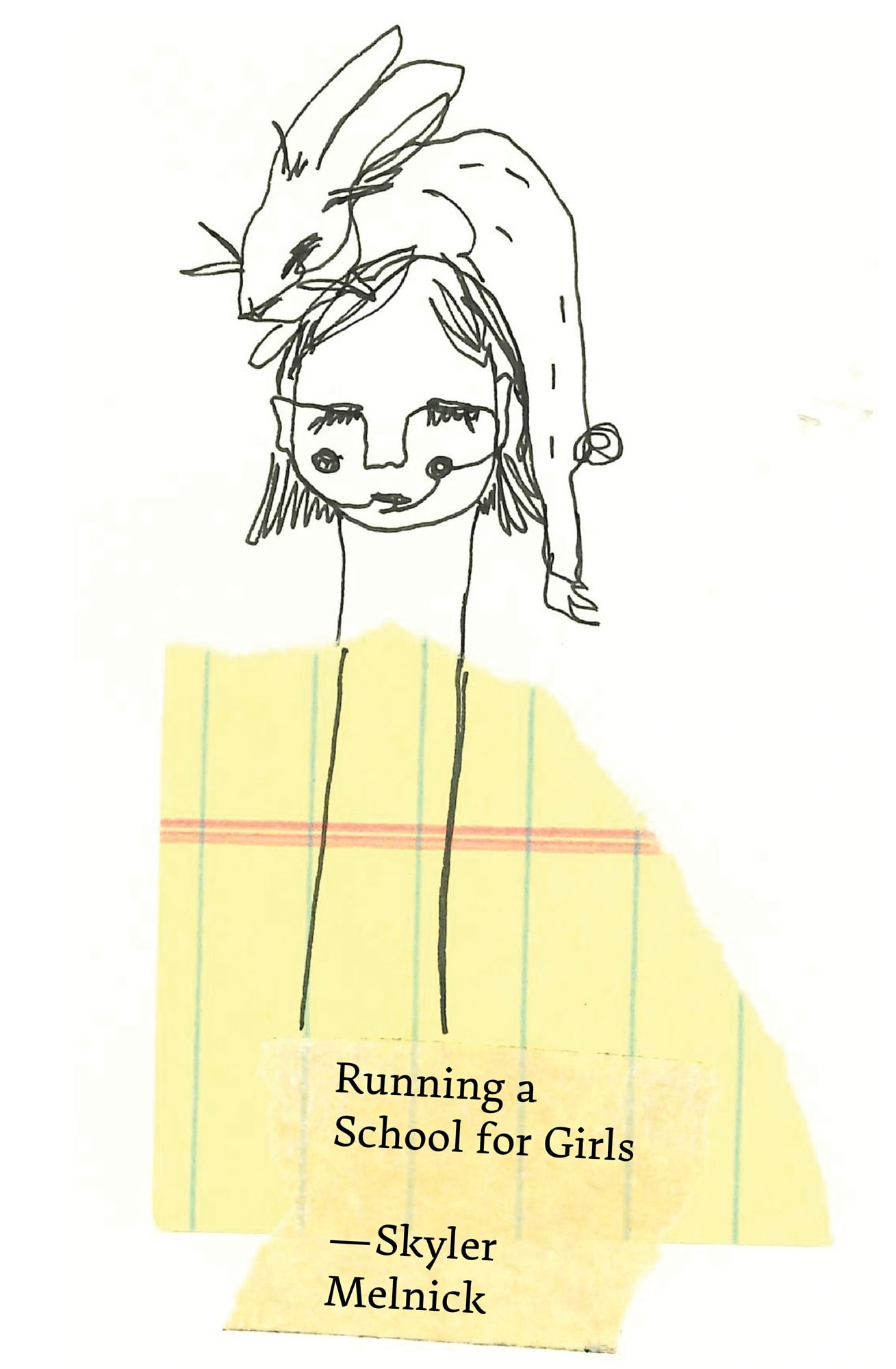

Running a School for Girls

Seventeen little girls stand at the edge of a cliff. The water below is black, lifeless. They jump into it.

I’ve been rowing for hours, collecting them from the lake. My arms burn as I push the oars. Girls coat the boat––behind me, in front of me, slivered on all sides of me. I fish another out, she nuzzles against the rest.

Last week, I pulled them from trees. Climbed for them while they dangled at me, giggling. I had to tug their bodies, tug them by the ankles until they yielded. These girls––you can wrangle them, put them back in bed, tuck them in tight, lock the door even. But it’s only a matter of time until they’re gone again.

Running a school for girls will change your life, my mother told me. Give you the chance to rewrite your childhood! My mother didn’t tell me this. My mother is dead. My mother is so dead that I’m hardly sure she ever lived.

I want to give up, but there are three more. Redheads, the triplets, shouldn’t be too difficult to find. If only the sun would rise and the fog would abate. Red bobs underwater like kelp and I row toward it, pluck out ponytails. The girls attached to the ponytails are pruned and their eyes burn pink, but they are alive, and we are homeward bound.

Home is an old brick building by the lake. Where I’ve worked since my mother’s death. And before her there was my grandmother. I did not choose this life so much as it was thrust upon me. Upon me these children were thrust, and after they are grown, this final round of them, there will be no more taken in. There will be only me, and the property, and freedom.

For now there are the girls, seventeen of them. They line the breakfast table like soldiers. The cook circulates, spooning porridge. She has no teeth, but still she smiles. The girls do not, nor do they speak. Sometimes they move their eyes and twitch their mouths at each other.

I was a child once too. Even had parents, unlike these girls. These girls do not know what it means to be cared for. These girls wouldn’t know care if it slapped them in the face, pulled them underwater, tied them to weeds and let them drown.

If we die, all of us––the girls, the cook, the tutor, the groundskeeper––who would know? Maybe the mold in the bathrooms does us in, or something more silent, carbon monoxide breezing through the building like perfume. Or something larger, a grandeur we never found in life. A fire, our bodies melting into each other like porridge.

Mommy! Seventeen little girls pound on my bedroom door as the sun goes down. Mommy! Mommy! Mommy! Mommy! Mommy! Mommy! Mommy! Mommy! Mommy! Mommy! Mommy! Mommy! Mommy! Mommy! Mommy! Mommy!

The door shivers from the thirty-four fists tap tap tapping against it. They are a mutinous pack. When they aren’t silent, they’re ravenous. Food doesn’t sustain them. It’s me they’re hungry for. On nights when I don’t give myself to them, they sneak out and disappear, determined to die.

Tonight I do as is simplest and let them in. The pack swarms my bed, nightgowns upon nightgowns. The triplets slide under the covers. A handful sit on the comforter. The rest wrap their bodies around the bed frame like ivy. They smile with their eyes, hopeful, like they’re about to receive a mother’s love.

I hardly had it! I want to scream at them. You’ll be fine without it! Just look at me!

Storytime? one whispers. Storytime, the others agree. Soon it’s all hissing. Ssssstorytime, the word slithers around us. None of them know what a story is.

First story, I tell them, is about mothers. Their eyes widen.

Mothers, I say, looking into a pair of eyes, then another, then another. Nearly all brown, like mine. This does not mean I am their mother.

Mothers push babies out, I go on.

The girls nod.

I––I point to myself for emphasis––did not push you out. You have to know that I am not your mother, not yours, not anyone’s. Say it with me.

I am not your mother, we all say it together. We repeat it, and repeat it. I conduct them like an orchestra.

I tell them one more story, about the dangers of leaving their beds at night, and then they drift off. They are adept at slumber. Their slumber is unanimous. I transport sleeping bodies to their bedroom down the hall. Two by two, a girl under each shoulder, stuffed into the hollows of my armpits. On my last round, just one child is left, the odd one out, the seventeenth. I think about squeezing her until she crinkles, like a can of soda. Or rolling her into a rug, and rolling it off the property. I do not do this.

I return to my bedroom, deadbolt the door, and hide under the covers.

Morning whips me across the face and the covers come off. It’s Sunday. The staff is off, and it is only I. I and the day and seventeen little birds.

Grab the rope, I tell them. It’s outdoors time––formerly me, alone, walking off the woes of the week. But the girls followed, they always follow.

We circle the property, the rope of girls undulating behind me. We weave through trees, hop puddles, climb fallen branches. They find a wounded rabbit, insist we bring it home. They insist like rabid coyotes sinking teeth into my skin.

Fine, I say. Fine! Take the rabbit, take the whole goddamn forest!

The rabbit isn’t ill. It’s pregnant, about to burst. Before long, we have 10 fresh bunnies, nursing themselves to life.

The girls walk on all fours, hopping around the building. They decide they are bunnies too. A school for girls who have decided they are bunnies. I could skin them and eat them. I have never eaten a child.

I have never eaten a child, I tell the jury. What I mean to say is hurt, I’ve never hurt a child. But I’m hungry and the testimony is taking forever.

I wake up sweating. There are many bad things I could do, but I have not done any of them. I have not done anything. My life is a marble, and it is rolling away from me.

Along with bunnies, the school accrues an array of pets. Beetles speckle the walls like dalmatian spots. Mice everywhere. Cats chase the mice. A snake slinks around the banister.

These additions distract the girls. The girls are delighted by all the commotion. They hop up and down steps, scurry like mice, prowl like cats.

These distractions provide me with time to myself, a small amount. But it’s mine. I deadbolt my bedroom door and stare at the mirror on my wall. I watch myself. My self watches me back. My self mutates. My self becomes my mother.

Mother, I tell her. We can’t keep doing this! Mother, mother, on the wall. She doesn’t speak to me, but I’m used to it, she hardly spoke to me in life. I was only one of the girls at the school. Did she know I was her daughter, that she was supposed to be mine?

Mother, it’s happening tonight, I whisper. I’m running away, running from the school for girls. She frowns at me. Her eyes droop.

I’m not going to abandon them! I tell her. I’ll find a new headmistress, a better one. You were right all along, I tell her, I want her to know she was right. Children are disturbing. Children are disturbed! Our lineage is diseased by children.

Fists pound on my door. The door pounds on my head. I’m not your mother! I tell it. I look to the mirror and my mother is gone. It’s only myself. My hollow, hollow self. Cheekbones like holes. If I’m not quick, the girls will burrow into me.

There are many ways to go, as the girls have shown me. The girls have shown me that going is an art. I take the rowboat. The lake encircles our property, like a moat, but continues beyond us. I seek this beyond. The sky darkens and so does the water. I traverse the darkness, away from it, toward it.

I wake under the moonlight. The boat has gotten smaller. It has gotten stuffier. I’m surrounded, that’s why. All seventeen of them, swaddling me. They’ve brought animals too. At the bow of the boat, bunnies suck their mother’s teat. Mice huddle beneath them, hurling their bodies against the wood.

The rowboat docks, back where it started, and the girls carry me up the stairs, 34 arms united, ants dragging home a carcass. They tuck me into bed, take turns kissing my forehead, and I sleep, sleep with my eyes open. I am a headmistress with holes. I am a headmistress infested.

On Sunday I’m taken outdoors, for outdoors time. I latch onto the rope, and the girls lead me. We swirl, we circle, we zigzag. I am getting smaller, they are getting larger.

I am running from a school for girls, I tell my mother’s ghost. A school for girls is running me.

There is no more alone time. The girls surround me always. We look in the mirror. At our reflections. The girls bang on the glass. My mother disappears.

I disappear again, try to. Into the trees. Takes them almost an hour, but they find me. They will always find me.

I pray every night for them to grow up, but they remain girls. Adulthood never comes for them. Meanwhile, I age, quickly, years ticking by like hands of a clock. I age into my mother, and then my grandmother, and they bury me, under the property, dig me up when they are lonely, then put me right back.

Skyler Melnick is an MFA candidate for fiction at Columbia University. She writes about sisters playing catch with their grandfather’s skull, boarding schools of murderous children, headless towns, and mildewing mothers. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Vestal Review, Flash Fiction Magazine, Moon City Review, and elsewhere.

Instagram: skyskkyy