Etheria Film Festival 2024

Bloodletter partnered with Etheria Film Festival, one of the world’s most respected competition showcases of genre films directed by women, to review nine short films selected for the 11th edition of the festival.

Bloodletter partnered with Etheria Film Festival, one of the world’s most respected competition showcases of genre films directed by women, to review nine short films selected for the 11th edition of the festival.

The Shadow Wrangler sits at the precarious juncture between erotic fantasy and embittering reality. In Grace Rex’s short film, “36 year-old freelancer” Nan, a frustrated creative who narrates erotic novels for a living, has a confrontation with the “residual discomforts” of her recent miscarriage. The sailor-mouthed Nan appears to have been hardened by the experience, although it’s quite possible that the gruffness that hangs about her like smog has always been a defining trait of hers. Her soft-spoken ex-boyfriend Bobby, on the other hand, is so gentle in his request for closure that it is hard to believe that they ever made a good match. Not that there’s anything wrong with this reversal of traditional roles. In fact, Rex’s subtle touch, evidently weaned on a diet of 70s psychothriller and the more recent feminist revival of the genre, hints that Nan is aching for permission to dismiss her abortive relationship and pregnancy with a masculine shrug of the shoulders. She wants to grant herself this permission, but something holds her back.

We soon understand what separates Nan from the closure she craves: erotic fantasy. Through a series of dream-like sequences that accompany Nan’s narration of the erotic Western she has been assigned to record, the tale of a beautiful damsel pursued by a bloodlusting cowboy warps according to the dictates of Nan’s mind. While the characters in the novel at first appear slightly miffed that their actions keep being interrupted by noisy disturbances in Nan’s apartment, the barrier between fiction and reality is soon transgressed altogether. A rabbit found on the ranch in the novel hops out of Nan’s impromptu recording studio as she attends to Bobby, who has returned to her apartment to debrief the miscarriage. Nan dismisses the nightmarish end to her pregnancy as a “totally normal night sleep” because she would lose face to admit that it deeply affected her. The trite but effective visual analogy of empty apartment to womb encircles the fact that Nan is reeling from the loneliness within. Perhaps Bobby was not the best partner for her, but her void has to be filled somehow.

As though to flirt with this idea, Nan fantasizes herself into the fictional plane of the novel, cavorting with every character we have thus encountered in the film’s most phantasmagoric sequence. As Nan approaches a climax that will end in tears, her housecat preys upon the rabbit that has escaped from its fantastical confines. We don’t fault Nan for going through a rolodex of grotesque sexual positions with the other characters, just as she does not fault her cat for ravaging the furry intruder. By blurring this story-within-a-story scaffolding, Rex asks us to consider: does the instrument of fiction complicate and expand desire, or does it flatten it, turning it into little more than animalism? How do we (as women, of course) contend with these contradictory impulses that simultaneously pull us towards hardened perseverance and arousing resignation? Just as it is about to boil over with tension, the film ends with the phantom presence of the eponymous Shadow Wrangler forcing entry into Nan’s apartment through the front door that mysteriously will not remain locked.

There’s no one there for Nan to be afraid of, “nothing to see” except shadows, as the voiceover intones. The fictional is finally stripped away, and Nan’s real experiences of fear and abjection create a looming emptiness that furnishes her with a self-made terror so palpable that it might as well be reality. The ending is a bit underdetermined, not quite coming to this conclusion so much as gesturing to it, but any doubts that the audience has about the themes in which Rex seeks to traffic are soon clarified by the expertly chosen song that plays over the credits. “I always wanted a bad boy,” the voice sings, “but now I’m the bad boy.”

Claire Orrange is an American writer residing in Brooklyn. She typically sticks to fiction, but in those moments when she strays to criticism her dashed dream of being a scholar of the Gothic briefly reawakens.

Instagram: hyperpopprincess

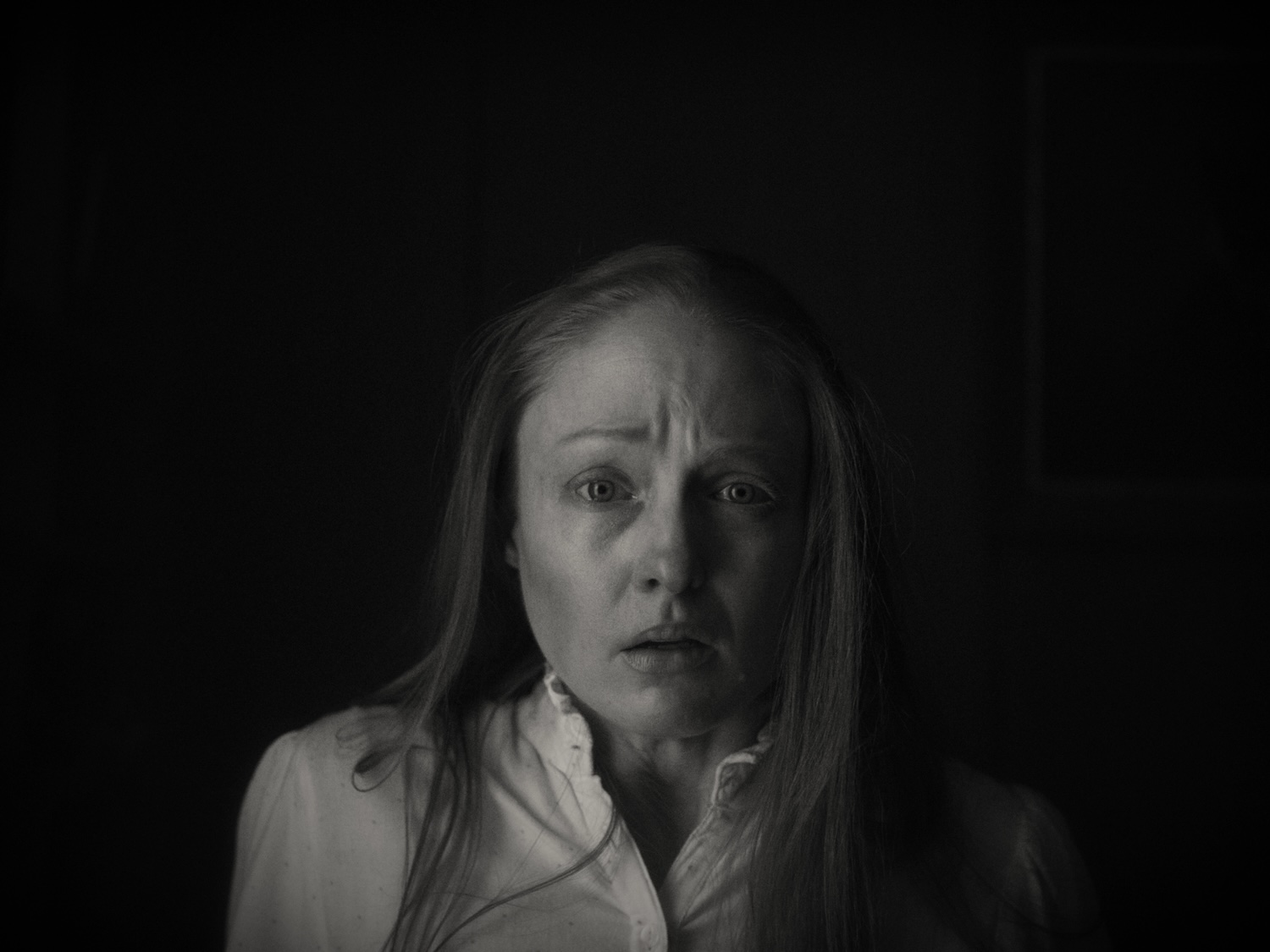

In The Thaw, millennial anxieties about having to move back with your parents travel all the way to the 19th century. Fragile Ruth comes back to her parents’ household at the brink of the fierce Vermont winter. She was banished by the man she was offered to, who claims she is barren. Nothing is new under the sun: the failure of a young adult to attach themselves to a financial unit separate from the one they were born into is damned to result in shame, and cause strain to the poor parents who thought they can enjoy retirement and some privacy at last.

There are not enough provisions for three, and in an effort to save their daughter, Ruth’s parents decide to take the “sleeping tea” and go into hibernation. The dangerous fate which they accept upon themselves goes worse than expected. An early thaw (the contemporary terror of global warming too, is copied to the reality of humans two centuries back) causes the father to wake up prematurely. As soon as he rises, the man devours Ruth’s beloved sheep, her only possession. Covered in blood, he continues to seek more food. His hunger cannot be fulfilled, and his appetite soon becomes an all encompassing, terrifying desire which recognizes no taboo. Remembering that Ruth was already punished by her husband because she was not fulfilling her womanly duties as a child bearer, we now again see her as subject to gendered violence by her parent. The once gentle, loving man turns into a beast. In this narrative, a young woman’s refusal to provide food and sex gives birth to what we really call Horror.

In beautiful black and white cinematography, Sarah Wisner & Sean Temple give stage to acting and art rarely seen in a short. Admittedly, there was a slight gap between actors casted for parents Toby Poser (Alma) and Jeffery Grover (Timothy), who let their maturity shine, and younger Emily Bennet (Ruth) who took it far at times, expressing unconvincing agony. But beauty always deserves forgiveness, and overall Bennet led this piece artfully. In The Thaw, one will find complexity and subtlety almost atypical for a horror movie. While being scary and uncanny, this isn’t a campy pull of red corn syrup and googly eyes. Careful writing and a well calculated soundtrack will lure you into a territory of layered fear, the kind that lingers past your bedtime. Lastly, and more importantly, this short contains a rare element of hope. Our heroine, the misfit, represents touching strength and courage. With only three actors on screen, a certain intimacy takes place between the work and the audience, which in turn allows a fresh view on what it really meant – or still means – to be a woman and want to survive outside the marriage structure.

Alina Yakirevitch is a Russian artist, filmmaker and writer based in New York. She holds an MFA from Hunter College. Her work was shown in Hauser and Wirth Gallery, New York; NADA Fair, New York, and NADA Miami. Recent shows include: Tongue Tied Diver, a solo show at All St Gallery, New York; Frozen, two person show with Anna Sofie Jespersen at All St Gallery, New York; What is and What Should Never Be, two person show with Martine Flör at Neuer Kunstverein Wien in Vienna, Austria; Little Light of Mine, two person show with Craig Jun Li at P.A.D Gallery, New York; Fire Exit, 205 Hudson Gallery, New York; and Swap Meet, P.A.D. Gallery at NADA Flea, New York.

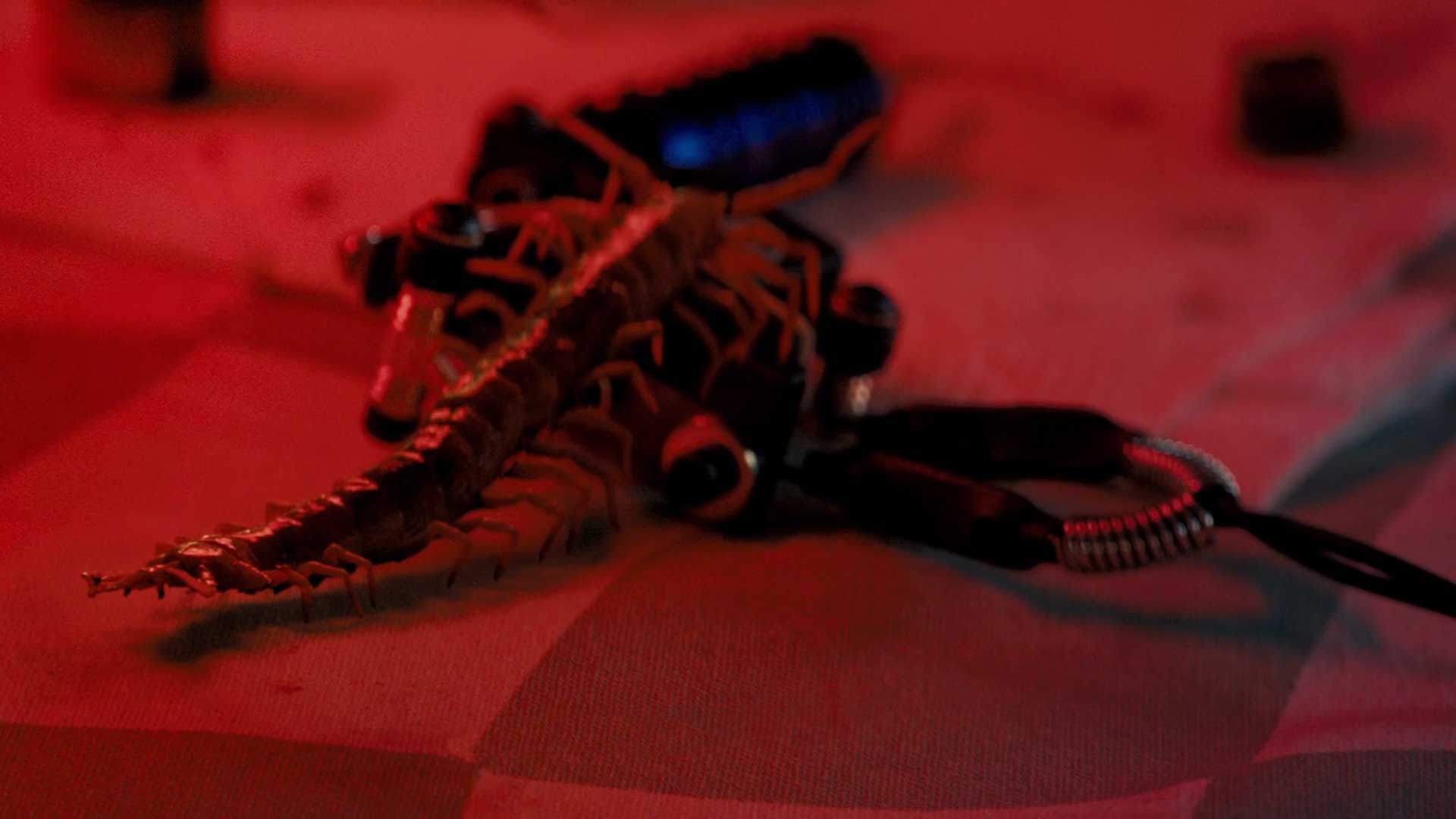

Screening at this year’s Etheria Film Festival, Sofie Somoroff’s short horror film Ride Baby Ride is almost a spiritual origin story of the John Carpenter directed movie adaptation of Stephen King’s possessed automobile terror Christine (1983). Celina Bernstein stars as a mechanic looking to purchase a 1978 Camaro, but unfortunately the sale comes with a nefarious exchange. Whilst working on the car back in the workshop, the mechanic discovers that her dream car is much more of a nightmare as she is attacked by the entity that is contained within.

Ride Baby Ride subscribes to the ideology that when a great trauma occurs, it can leave an imprint on a place, whether it be a house, a community, or in this case, a car. The film opens with a common situation in which a woman is just attempting to exist in this world, and carry out a completely normal task (buying a car) which is then completely ruined by the actions of misogynistic and toxic men. This interaction then implants its memory onto the car, leaving the mechanic to face her trauma and the PTSD associated with it whilst working on the vehicle. The car becomes a symbol of not only the horror she has had to face, but also that of violence and misogyny experienced the world over.

Bernstein’s nuanced performance is one that portrays a strength which comes from being a little bit broken, one which a majority of viewers are sure to find relatable. The acting and narration strays from being too exaggerated which treats the subtextual matter with much needed care, and with a ‘good for her’ conclusion in the final sequence proves that facing life’s demons will always lead to the best possible outcomes.

Ride Baby Ride is a retro ride from hell bringing a fresh take to the haunted subgenre of horror.

Ygraine Hackett-Cantabrana is the host of What A Scream horror podcast as well as editor of WhatAScreamPodcast.com, and the co-host of Gore Things, the podcast that explores splatter films with Brad Hanson. She has by-lines in Moving Pictures Film Club, Ghouls Magazine, Fangoria, and Dread Central and has recently edited and published the zine Mirror Mirror: Reflections from Women on the Horror Genre.

Instagram: whatascream

X: what_scream

Are you a millennial or older Gen Z who spent your childhood and teenage years watching weird horror shorts play on Adult Swim? Do you find yourself unwinding to 90’s commercial compilations on Youtube? Do you love pizza? If you answered “yes” to any of these questions Talia Shea Levin’s Make Me a Pizza is just what you’ve been missing.

The short centers on a woman living in a McMansion best suited for pornos, who is desperately trying to seduce the pizza man. While she discovers that sex isn’t a good payment for pizza, the delivery guy discovers there was even more to the creation than he could have ever dreamed. The two engage in some gooey cheesy body horror sex reminiscent of the shunting, until they are able to transcend humanity and meet the pizza god.

The short is gross, funny, and highly stylized. The set decoration is phenomenal; you really feel like you’ve been transported back to a time when the CRT TV ruled the land and VHS was king. Make Me a Pizza was filmed on Kodak Film, and boy does it show. Everything has a weird halo glow, like you’re watching something that was recorded on tape that has been played way too many times. The main character’s house is a late 90’s/early 2000’s Tuscan dream with high windows and earthy tones. The dialogue is hilarious and both actors are nailing the tone. Sophie Neff is phenomenal as the deranged pizza cultist who seems to live in a porno world, while Woody Coyote is a great foil as a not-so-clever pizza guy who just wants to get paid.

It is a great subversion of what we’ve come to expect in the media with men being sex pests. Or at least willing to accept whatever gets thrown their way. Make Me a Pizza also greets the viewer with a scathing critique of capitalism that I wasn’t expecting going in. Flashes of workers gathering ingredients are accompanied by a great speech from Coyote about how skipping out on paying a delivery driver ends up harming a lot more than just one person. While our main character stays in her 80’s vaseline lens covered mansion daydream, the delivery guy has to leave this otherworldly realm to go back to his beater car and deliver more pizzas.

Between the sets, the performances, and the special effects, everything comes together to make this a good cheesy time.

Kourtnea Hogan is a queer horror hound from southern Indiana. Raised on Stephen King novels and 80’s horror movies, she fell in love with the genre at a young age and never looked back. She makes horror movies under the name Kourtnea Zinov’yevna.

Killing people is hard. Raising them is harder.

In 1 in the Chamber, a comedy-action short directed by Annie Girard and Diana Wright, two female assassins go head-to-head when one of them is accused of selling their company’s trade secrets. The catch? When the hitwoman shows up to bump off her colleague, she finds out that her mark is heavily pregnant.

This revelation would probably make even the most seasoned hitman, or hitwoman, reconsider their assignment. Not our girl. No baby-to-be is going to stand in her way. When she sees her pregnant colleague, she pulls out her gun and aims at her head.

Our assassin’s only problem? The house has been baby-proofed. Her mark roundhouse kicks her gun into a diaper pail, locking it out of reach. (A hilarious back-and-forth ensues later in which the mom-to-be tries to teach her assassin how to “push-twist” open the child lock.) The women try to strangle each other with breathable sheets and blind each other with ‘no tears’ shampoo. Heads are banged into squishy corner guards and bookcases, which should be thrown, are bolted to the wall, immovable.

Like all great physical comedy, the gag-per-minute ratio in Chamber is ridiculously high. The fighting, also, is highly skilled. In between these prop-gags and punches, the women also maintain witty banter, joking about the ridiculousness of baby paraphernalia and the sky-high expectations placed on new mothers today.

Chamber follows in the footsteps of Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022), a movie that upended viewers’ expectations of the action genre. Instead of centering the narrative on a hyper-masculine or hyper-sexualized protagonist, which is the norm for action movies, both Everything and Chamber gave physical power to the powerless and overlooked. In Everything, the action hero was an older woman of color, who owned a laundromat and was in trouble with the IRS. In Chamber, it’s a pregnant woman, and it’s incredibly cathartic to see her deliver a flawless jab-cross.

At the end of the film, there’s a twist. I won’t spoil it here to preserve your untainted enjoyment, but I will say that the filmmakers make it clear that they are using this comedy about assassins to interrogate real problems for mothers in the workplace.

Pregnant people exist in a strange lacuna in our society. They are appreciated, but only instrumentally. Once the child is born, a mother’s value plummets. I mean this literally. On average, mothers experience a 5% decrease in salary per child. They are assessed as less competent than non-mothers of equal competency. Bias exists in nearly every industry, even, apparently, in the assassin business.

1 in the Chamber is funny until it’s not. We laugh until the movie’s over. Then the lights come up and we realize we need to wedge our pregnant stomach through the endless rows of movie theater seats that weren’t built to accommodate this type of body. We need to waddle fifteen blocks without help, even though we are tired, hungry, and need to pee. And then we need to stand on the subway home because no one will give up their seat. It makes us mad. Maybe even mad enough to kill.

Shelby Heitner is an MFA student at Brooklyn College and a Fiction Editor for the school’s literary magazine, The Brooklyn Review. Her writing has won contests at the New York Times and Lincoln Center.

Brea Grant’s MLM follows a debt-stressed millennial, Sarah, through her participation in a legging-centric pyramid scheme in an attempt to make some easy money. After all, the vaguely sinister, barely satiric (in the sense that it’s hard to make the content it riffs off of any more ridiculous) ad the film opens with promises of Girlboss status and wealth, seemingly without effort, all while sitting at home! However, things quickly spiral out of control as Sarah fails to reach sales quotas despite her desperation-tinged, ring-light-framed Instagram Live sales sessions, and soon, Sarah experiences consequences ranging from comically disturbing to downright murderous.

There are very few things that keep me up at night. Growing up, I was scared of everything. Kidnappers, rattlesnakes, serial killers, ghosts, being thought of as uncool, spiders, demons, singing in public. Unsurprisingly, for most of my life, I was unable to watch horror movies. Then, during the first year of Covid lockdown, I became obsessed. In 2020, I watched 60 horror movies; in 2021, 80. I desensitized myself to the degree that my rewired brain doesn’t even conjure nightmares anymore, or if it does, I find them more entertaining than frightening.

The things I do get anxious about enough to lose sleep over are, at least to me, “real” fears. Being unable to get a job that justifies having gone into student loan debt, getting injured without healthcare, my cat getting sick (again) and the accompanying vet bills, my mental health deteriorating, the numbers in my bank account. Unlike being possessed by a demon or stalked by an axe murderer these are all possible (conceptually an axe murderer could stalk me but the odds are statistically pretty against it), some of them are realities. The most memorable horror movies often contain slivered versions of our fears and ourselves.

Watching MLM, I was confronted with fears that aren’t so far from reality. Sure, no one’s penis is turning into a live animal, food isn’t suddenly becoming inedible, that axe murderer remains statistically unlikely. But the real fear at the heart of Grant’s short is financial anxiety, the precarity of maintaining a stable life in America with which so much of the country lives. The almost manic terror Sarah feels while trying to sell multicolored leggings on Instagram Live is a desperation tightly woven into late-capitalist work culture. The hopelessness of watching while others succeed at their legging-funded American Dream (at least, the millennial version of it) while she flounders to do the same, unsure what she’s doing wrong or if she’s just inherently incapable of success is a familiar one. As her failures continue, the consequences compound until they threaten to literally split her head open.

Sarah, like so many Americans, lacks community and the support it can provide. Her husband is about as interactive as a goldfish and she never even considers reaching out to him for help. The only other person in her life is her “upline,” the Instagramably perky Molly, who got her into the pyramid scheme in the first place and is only superficially interested in Sarah’s well-being until her own life is put in danger by Sarah’s inability to reach her sales quota. Sarah’s situation is particularly scary because she is alone—her husband can’t even see the punishments that La La Leggings inflicts on her. Molly is cheerfully unconcerned about Sarah’s situation until it directly becomes her problem. The successful La La Leggings “family” members aren’t a community for support but rather a source of further isolation.

As they smile through their own sales sessions and lounge at home in #OOTD post-worthy ensembles while chastising her for not selling enough, they flaunt the apparent ease of their success and extoll the fun they’re having selling leggings in front of the webcam, the implicit message is obvious: I made my money and my life is great, so what’s wrong with you? Just like the cutesy-cringe millennial tee shirts the La La Leggings girls wear in their commercial, the message is deeply familiar to anyone who’s spent any time on Instagram—a space that supposedly connects us but only allows us to see the very best versions of each other’s lives, that alienates rather than brings together. Sarah is only freed from her entrepreneurial hell when she gives up on the illusion that she could be the kind of Girlboss that Molly appears to be, but she’s no better off than she started, with no community and no obvious source of income. Grant leaves her protagonist and her viewers alone and uneasy—the fears at the heart of MLM are inescapable, in Sarah’s reality and ours.

Cloe Wood studied political science and creative writing at the University of California, Berkeley. She writes, watches horror movies, and works for money in Brooklyn, New York. You can find her work if you say her name three times and look in the bathroom mirror, or with a Google search.

I like to think of myself as a zombie expert. I was a zombie on The Walking Dead (2010–2022) and a ghoul (a dry zombie) in Goosebumps (2015). While this may sound pretentious, the prerequisites for these zombie roles were locale, a thin physique, and big eyes. Plus, my times on set were long and, at times, monotonous. We zombies were rushed through wardrobe and makeup to get ready to…well…wait. We were stuck in place, waiting to be needed, usually pretty hungry and bored out of our minds.

Faye Jackson’s clever and darkly humorous film, Ten of Swords, opens with Jay finding himself in a similar situation when he darts into a bathroom and examines his freshly zombified face. From there, Jay is taken to the PPR, aka a “Post-mortem Recruitment” facility, where he’s assigned menial tasks.

At first, Jay thinks being a zombie is alright. He can deal with the monotony of his job as he gets fresh meat every day and has little memory of his previous life. But, his world gets turned upside-down when his zombie co-workers point out a startling difference between them and Jay. Jay is considerably younger and literally has a knife in his back.

You see, in the world of Ten of Swords, selling your body to the PPR after you die is a way for desperate folks to get money for their loved ones still living. The dying must consume a zombie parasite, and after they reanimate, the PPR forces them to work mindless jobs. Therefore, Jay’s youth and back-stabbing indicate he ended up there in a very different way.

In case you don’t know, the titular tarot card of “Ten of Swords” is not a good one to draw. It represents betrayal, failure, and finality. There is no escape from the reading, but if you’re strong enough, it offers a chance for closure and renewal. Even with this positive spin, it’s clear that drawing the Ten of Swords card means that life, maybe even death, is going to absolutely suck. And that is exactly what Jay, after remembering why he has a knife in his back, discovers.

Now, while you may think you’re a zombie expert, let me tell you that Ten of Swords spins the zombie genre on its head. I mean, we’re seeing the story from the zombie’s perspective (and shut up about Warm Bodies (2013), it doesn’t count). Take that ingenuity along with incredible world building, the astute dialogue by the lead zombies, a timeless blues soundtrack, a buzzing and disorientating sound design, and endlessly thought-provoking societal and mortality themes, and you’ve got the kick-ass Ten of Swords that is going to leave you wanting more. Come on, Faye Jackson, give us more!

Jennifer Trudrung’s love of horror stretches both in front of and behind the camera. As an actress she’s appeared in film and television series, including The Vampire Diaries (2009–2017), Goosebumps (2015), and Halloween Kills (2021). As a screenwriter and producer, she’s built quite the filmography of short horror films, including the upcoming Hickory Dickory Dock, and the award-winning short films Here There Be Tygers based on the Stephen King story and Unbearing. Jennifer has also written several award-winning screenplays including Spectrum and Nighttime Is No Fun Anymore. Jennifer is the mom of two incredible daughters and an actress signed with Bold Talent.

Inked is the latest short film from director Kelsey Bollig. This short is a bit of a departure from her 2021 Black Swan-esque (2010) short film, The Fourth Wall, which was one of my favorite watches at Final Girls Berlin Film Festival that year. Inked centers on Dylan, a woman who’s dealing with the recent passing of her father who died alone in prison. To honor his memory she asked her friend to tattoo her father’s ashes into her skin. Yet the loving gesture begins to have a troubling effect on Dylan and reveals a terrifying secret.

The film looks great and has a fun neon-drenched color palette that horror fans love so much. There are also some disturbing horror elements that Bollig uses to great effect. The main performances are very compelling and the two have a palpable chemistry. They are genuinely fun to spend time with. The main issues lie in the fact that they do not give the main character Dylan much to actually do. She has some great final girl, kick-ass energy that we don’t get to see come to fruition. That coupled with its easy to predict plot twist make some of the horror a little lackluster.

However, the film does center around an interesting, and rarely spoken about social issue. While it mainly uses the prison backstory for the plot elements, it is a reminder of how many families are actually affected by mass incarceration. As of 2022, roughly 1,230,100 people are incarcerated in prisons throughout the United States. The latest statistics show that about 1 in every 2 adults has had a family member incarcerated. While there are a variety of issues in regards to the state of mass incarceration in the United States, we do not often think about the amount of people who deal with the horrifying realities of our broken prison system every day. It means potential breadwinners are unable to support their families, children grow up without essential guardians, and this time away from family only adds to the mental strain on both sides of the bars.

About half of people in prison are parents, just like Dylan’s father. They miss out on major milestones in their children’s lives. The story of Inked centers around an important issue that many of us don’t think about. Many of us are privileged enough to not think about prison, or the people inside of them. Dylan missed out on time with her father and had to travel to a scary, often stressful place to get even a fraction of time with him. The horrors she faces in the film are also the result of a clerical error, in an institution that is often unfeeling to the people and families attached to the justice system. Many of the horror stories we love so dearly are tied up with horrors rooted in real life, making them all the more effective on the right viewer. Inked is certainly worth the watch, as well as Bollig’s other shorts. And while you take the time to support independent filmmakers, perhaps you can also take some time to think of the real life backdrop.

Visit The Prison Policy to read an article on the effects of incarcerations on families in our country.

Pairs well with Media Like:

Tori Potenza (she/they) is a queer film critic and historian based in Philadelphia. They are a staff writer with MovieJawn and have published work for Nottingham Horror Collective, Slay Away With Us, and Certified Forgotten. She is a lecturer who has spoken at film festivals and schools. Her work often focuses on sex and gender themes in film along with body horror and posthumanism. Currently they are working as a shorts screener for Brooklyn Horror Fest.

Tooth is a creative, grisly body horror that prompts the viewer to ask what would happen if our own bodies decided to betray us. In the film, we see a woman conforming to the age-old routine of brushing, flossing and poking with nasty little interdental brushes, as well as eviscerating her enamel with whitening strips. Such routines are commonplace and we take for granted that our well behaved teeth will endure the torture. However, these teeth have had enough of being prodded and decide to stage a revolution. The results are delightfully gory, all bleeding gums and dripping blood as the teeth take their revenge. At the root (pun definitely intended) of this short is a primal fear, one that is explored with humor in Tooth. This short is well paced – at 4:33 minutes there isn’t a second of wasted time. Practical effects are always a delight, and this inventive short makes great use of them. It’s clear that Jillian Corsie is a director to watch, and I can’t wait to see what comes next.

Dr. Megan Kenny is a writer, researcher, folklorist and parapsychologist. She is co-director of the Monstrous Flesh Collective and co-host of the Monstrous Flesh podcast.