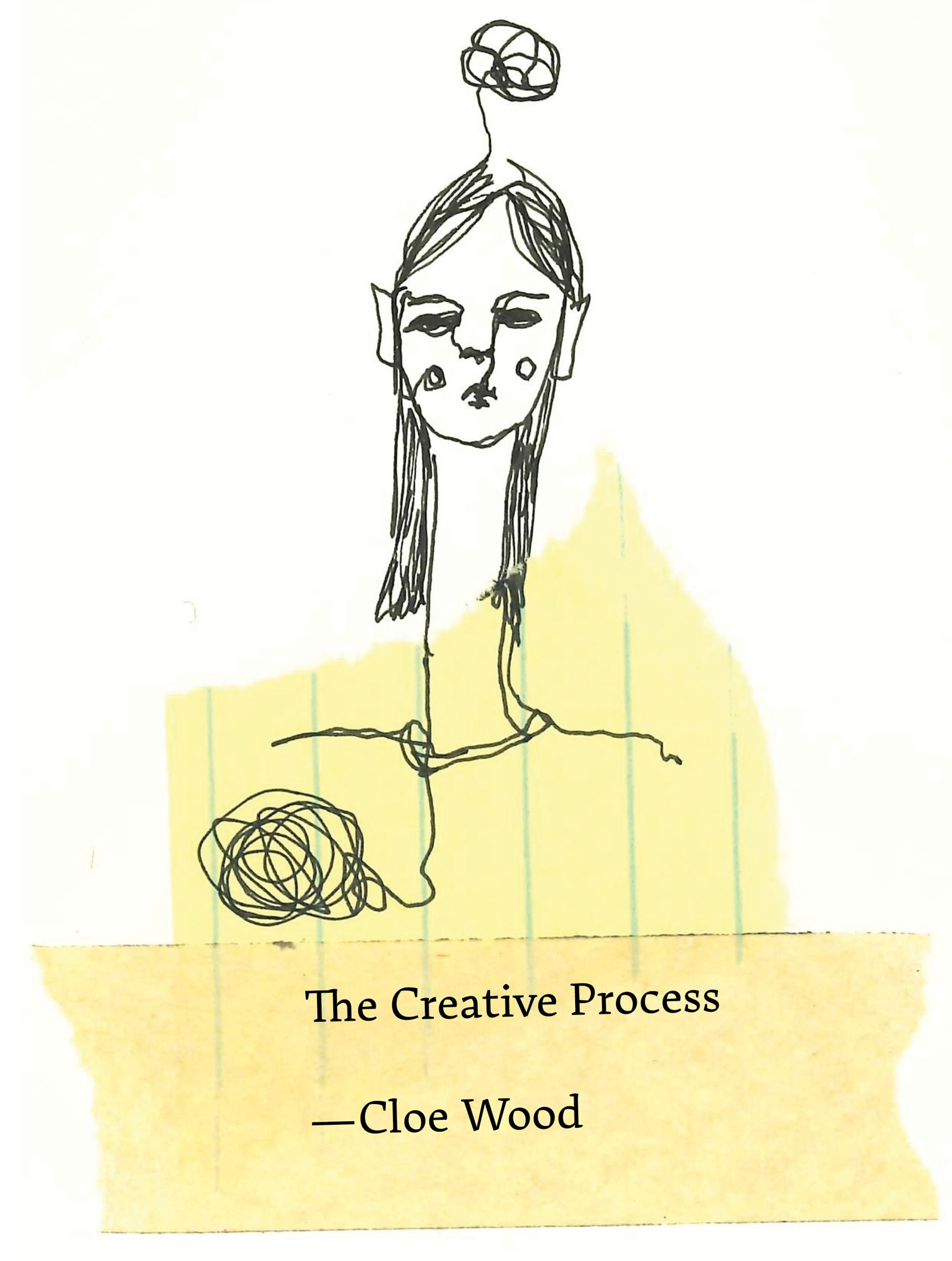

The Creative Process

The woman started to knit the socks almost entirely by accident. Or, she didn’t intend to make what she did. She felt the itch of creation in the curve between her shoulders and neck, not an unfamiliar sensation, but a provocative one. She had a few skeins of wool stashed away—thick, fibrous, pillowy stuff. She did not know what she was going to make, but she began by finding the color.

She started by soaking the wool in ice water and vinegar. She boiled water over a flame in the copper pot she used for dyeing things. She sorted through the bottles of dyes she kept in the cupboard. She mixed them intuitively, without an idea of what exactly she might produce.

She poured the steaming water into the jars of pigment, watching the flat color expand in bright clouds before darkening again. She wrung the loops of yarn back out into the bucket. Not bothering with gloves, knowing no one would see her hands, she began dousing the yarn with dye and working color into the fiber. She heated the yarn again over the stove until steam began to leak from the lid of the pot, and finally rinsed and squeezed out all of the excess pigment.

Once she finished, the woman hung the yarn out to dry in long loops across every surface she could manage: tables and chairs, banisters and lamps, from the beams that held the ceiling up and from the door knobs. The yarn in all its shades resembled a spider’s web. She rested a moment on the floor and surveyed her work, fingers twitching. The smells of vinegar and dust and lanolin hung in a suffocating cloud. She sniffled, stood, and walked past the window. She could hear the sounds of people outside. She didn’t wish she were with them, but for a moment she wished she were one of them instead of herself.

She kept her needles in a china cabinet she’d bought years before, because it was beautiful and made of dark wood that made her feel warm when she looked at it. The needles themselves were lovely and smooth and strong, arranged neatly by size. She ran her fingertips across their pointed tops and stopped at the largest set. They were so big she hardly ever used them. They could have been wooden stakes except that they were pointed at both ends and heavily lacquered.

She reached for the nearest strand of wool. It was wet and cold and rough, but the longer she held it in her hand the warmer it grew, matching her own heat. She clutched the line of wool in one hand and the needles in the other, and shut her eyes tightly. She could feel the shape of what she would make beginning to form at the edges of her mind, down her neck and arms and fingers.

She drew in a cold breath and opened her eyes. She would start a fire to dry the wool. She hadn’t lit a fire in months. Usually she layered herself in sweaters and thick socks and shawls and ignored whatever chill remained. The excitement in her chest pitched at the thought of the heat and brightness and hissing of the wood, of the way the concrete floors would take in the heat and reflect it back until steam came up from the wool. She struck a match and waited. Once she was sure the fire was strong, she stretched across the rug in the center of the room and closed her eyes.

When she woke, there was no light in the windows and the coals sputtered in the stove. She reached for the nearest strand of yarn. It was dry. She stood, already twisting the yarn into a ball, walking up and down the room, winding and gathering yard after yard into her arms. When she reached the end of the strand, she could hardly carry the ball in her arms. She dropped it at the foot of her chair and snatched her needles up from the floor. She didn’t bother to look for her glasses; she could knit without sight. She tied a firm knot and cast on hundreds of stitches. She began to knit round after round, spinning circles in rings of blue and green and purple, a galaxy of knots. She felt powerful.

“I want,” she said to the still-dying coals, “to knit a pair of socks so big you could fit an entire person in each of them.” What she thought was, what I really want is someone who really loves the socks, who thinks they’re beautiful. Someone who says, ‘These are the two most wonderful things I have ever seen.’ And the person, they would be so glad and they would say, ‘This! This is my favorite color, how fantastic that you should anticipate that!’ And I would smile because I know them as well as I know every stitch of the socks. And it won’t be hard at all.

The coals hissed in reply.

They will feel as comfortable in my hands as these needles, and they will love me with all of their being.

She swallowed and found her mouth was very dry. No one had ever asked her to make anything for them before. She knit desperately fast, ignoring the aching stiffness in the joints of her fingers.

“These socks will be perfect. They won’t have to ask anything of me because I will know how the socks are supposed to be. And we will climb inside the socks, each of us, a pair, and we will fit exactly.” She was crying now, ugly tears that fell onto the yarn in her lap, and the wool drank them. The coals whispered at every drop.

She kept working with numb fingers. Blisters formed on her already-calloused hands, and she worked as they popped and bled and oozed thin liquid. The wool accepted these offerings, too. She wondered if her fingers would break. The thought dissolved as she continued her work. Her stomach ground in on itself, and her lips cracked. Her eyes stung with lack of sleep, but there was no stopping. The coals glowed like wild eyes in the dark.

Finally, she picked up her shears, cut the yarn, and collapsed.

She opened her eyes to darkness and cloistering heat. She was on her back, on the ground, closed up and tangled in something. She tried to push away whatever cocooned her, but it resisted. Her whole body ached like she’d been beaten. She shrieked and tossed herself around as violently as she could.

“Are you alright?” asked a voice from outside.

She shrieked again and fought harder until an opening grew at her feet. She tumbled forward and out. She had climbed out of a sock, and there was another person, a man, peering out at her from its twin. She felt sure he was naked inside of the sock. She froze, unable to think of what she should do. This sort of thing had never happened before. He blinked at her and asked again if she was alright.

“Who are you?” she asked, and then, “What are you doing in my sock?”

She noticed that he was very beautiful. His face was almost obscene in its prettiness.

She thought maybe she should hit him with something or run away.

“These socks are magnificent,” he said, running his hand across the stitches. He touched them so gently. He smiled up at her, still laying in the sock on the floor, and she felt the same thrill she had when she’d begun knitting the socks the night before. “Thank you,” she said.

“The colors are amazing, these are really something. But of course they are, you are so talented.”

“I don’t understand,” she said, feeling dizzy. “How did you get inside?”

“There’s plenty of room, they’re really very impressive.”

“But how did you get inside my house? And why are you inside of my sock? And why aren’t you wearing any clothes?” She felt embarrassed.

He looked at her for a long moment.

She looked down at her hands, still stained purple and blue and green, and understood. She hadn’t expected him. Why should she? Wishes were granted so rarely. But here he was, a wish, or something like one.

She walked to the wardrobe and found some clothes that would fit him. He stood and dressed wordlessly, and she did not look away.

In the beginning she was happy. They didn’t have to waste time getting to know each other. They already knew. She had never felt so cared for, so interesting, or beautiful, or deserving of attention. He watched her knit, sitting for hours, just looking. He could sing better than anyone she’d ever met, and he never put too much salt in her food. He knew all sorts of wonderful things.

He asked her for her stories and she gave them. He never offered his own, but she didn’t mind.

He did all of her errands for her so that she wouldn’t have to go out into the snow and risk catching some terrible illness. She was a simple cook, having only ever needed to feed herself, but every meal she prepared drew praise. In the afternoons, they would sit together and read, or play cards, or listen to the radio. At night, they would lay in bed, and he would draw stars on her back until she fell asleep.

One morning he came home with a bucket of paint. She was amused at first, watching him carefully prepare his supplies. She thought maybe he was going to paint their bedroom a new color, something to match the large pair of socks they’d hung above the bed. She asked him what he was doing, and he smiled. He asked her to tie a scarf around her eyes. He wanted to surprise her. She smiled and shook her head and found an ancient silk scarf in the dresser. He tied it across her eyes so tightly it was actually a bit painful, but she didn’t complain. She sat and waited, grinning even as an hour slipped by, then another. For him, she was patient.

Finally, he lifted her out of the chair and spun her around. She laughed and pulled the scarf away. He had painted each window in the house entirely black. Then he had given them all another coat. Her first thought was that it would be difficult to tell what time of day it was.

“Do you like it?” he asked.

“Why did you paint the windows black?” she asked, unable to come up with a reason herself.

“So that we won’t have any distractions,” he explained, “no more people walking by, or birds pecking at the window, or snowstorms or stars. Just us.”

She blinked at him. He was so pretty and good, and he loved her. She tried to match his excitement, but her smile shook. He could see it, she knew. His heart was breaking.

She spent the rest of whatever stretch of time it was until they went to bed knitting in her chair. She wanted to make him a sweater to cheer him up, but she was dizzy from the smell of the paint and didn’t notice as stitches dropped off of her needles, leaving holes behind. She fumbled with the yarn but her fingers were slow, and the yarn wouldn’t move the way she wanted it to. She tried to use her fingers to weave in the stitches she’d missed. The fibers split and tangled as she picked at them with her fingernails. The holes in the work grew larger. She felt spurned. He sat across the room, watching her. Occasionally he got up and stood behind her chair for a while, looking over her shoulder. She felt violated by this observation of her failure, though she’d never felt that way when he’d watched her knit before. Each time she made a mistake her whole body cringed and she grew angrier, at the yarn, at herself, at him. When he kissed the top of her head, she ground her teeth and said nothing.

When they finally got into bed, he pulled her close, his nose pressed against her neck.

At first it wasn’t terrible. It almost felt like a game. He had been right, there was nothing else besides them. Their own small, dark world. She thought she might not miss the sun.

But soon it proved difficult for her to live with the darkness and stale air. Once, she could knit without seeing. Now, even in the candlelight it was difficult and gave her a headache if she worked too long. When the last candles burned down to nothing, no one replaced them. The only light in the house came from a fire in the stove, which never died out. For a while she tried to knit next to it, but the heat was stifling and her eyes stung. She left her needles on the table one day and did not pick them back up.

She tried to go outside after that, thinking it might do her good to walk around in the light. But the sun was so bright, the world was moving against her, and she was sure she would die from the pain that scraped inside of her head. She pressed the heels of her palms into her eyes until she saw black, and past that until dark patterns spun behind her eyelids. She hurried back inside then and did not go out again.

The two of them agreed that he would go out at night to get things when they needed them. She would stay home and rest.

Some time after the windows were blackened, a curious neighbor knocked on the door to ask why their house was opaque. The pair were startled, as they had never been interrupted before. She was interested, but he shook his head. They did not answer. They listened to the sound of bone and skin rapping against wood until it stopped, and they were alone again.

The days passed with increasing sameness, until she had trouble remembering what had happened when. It didn’t matter. He told her all the time how all he wanted in the world was to be close to her. He kissed her and smoothed her hair and told her he could not exist without her. She leaned into him.

She tried to scratch the paint off of the corner of their bedroom window once. Black flakes wedged under her fingernail, piercing her skin. It did nothing. She wondered if it was dark outside, or if he’d really applied so much paint that she couldn’t scratch through, or if he had coated the other side of the glass some time when she hadn’t noticed.

The clocks went wrong at some point. She thought maybe he was changing them, creating his own time, their own time, but she didn’t know for sure.

The water tasted wrong, or the food tasted wrong, or her own mouth tasted wrong. His mouth tasted wrong too.

She spent most of her time in bed, and when she woke up he was always right beside her.

She saw a spider on the ceiling one day and watched it spin a web.

He didn’t know when he realized she wasn’t enough of herself. She had faded somehow. He’d tried his best to accept it at first, but eventually all of her went dull. She smiled when she noticed him looking, but it didn’t move him the way it had before.

He thought maybe she was sick. He made her soup from chicken bones, boiled them down with herbs and root vegetables until a thin layer of fat shimmered across the surface.

He poured the broth carefully into the largest bowl he could find, and fed it to her in bed, spoonful by spoonful. He took her temperature with the back of his hand, but she felt wrong. He wrapped her in blankets that she’d made herself long before his arrival, but she stayed cold. He fed more wood into the stove until the heat in the house was almost unbearable. He read to her from her favorite books when she was awake, and kept vigil while she slept.

It did nothing. He could do nothing to return her to the way she’d been before. He felt that she was dying, and if that were true then he was dying too.

One day she slept too long. He was terrified. He couldn’t let her go, but he couldn’t stop her, either. He looked at her beautiful, sallow face until it hardly resembled her at all. She looked hollowed out. There was only one way he could think of to preserve them both, to keep her near him always.

He pinched her arm, just above her wrist. She blinked at him, dazed, but said nothing. He tugged and a strand of her broke loose. She opened her mouth with her eyes wide, but made no noise. When he pulled again, the strand grew longer. She unraveled in strings of skin and hair and sinew and organs and tissue and blood. His hands were stained and dirty, but he didn’t mind.

He gathered her up carefully, spooling and twisting her into a ball. She was warm and soft against his arms. He sat in her chair and set her gently in his lap. He tied the first knot the way he’d seen her do before and picked up her needles from where she’d left them. He mimicked the motions he’d watched her make so many times, round after round. It was hard work, but he was determined. His head felt light and open. He was giddy with the feeling of every part of her running through his fingers, brimming with love.

He had unspooled her, and now he would put her back together. Knot after knot she became something new and beautiful in his hands. He put down the needles and wove the trailing thread of her into the body of her new form. He draped her over himself, smoothing her over and feeling her completeness. She was exactly as he wanted her. He wore her then, and sat in the dark watching the fire in the stove shrink into small flames, to burning coals, to smoke.

Graduated from UC Berkeley in 2020 and lives in Oakland. Spends a lot of time knitting.

Twitter: arson_mommy

Substack: https://liquidbanjo.substack.com