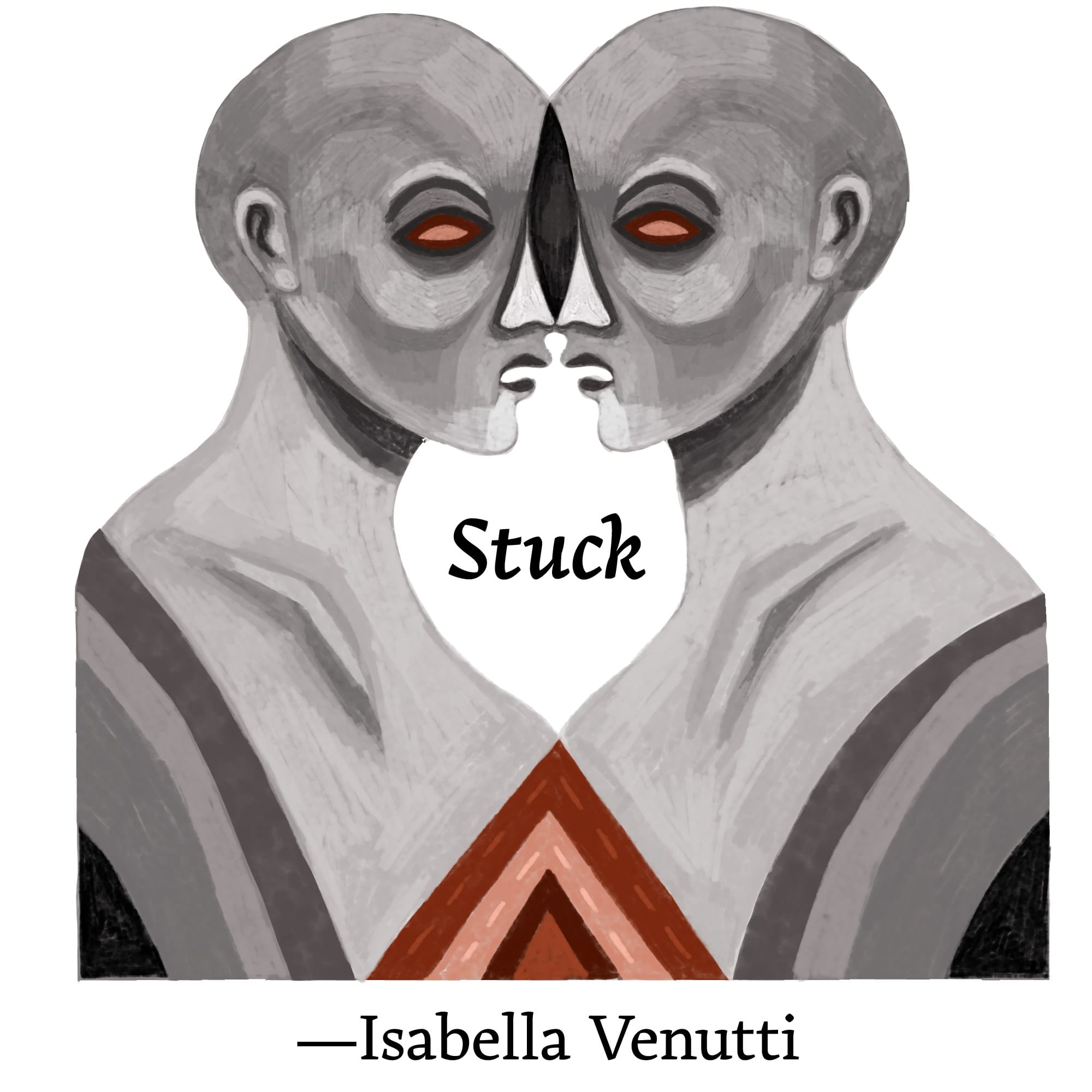

Stuck

I first got stuck when I was seven. A boy with a crooked smile who lived three houses down. He wasn’t special, not really. The soles of his sneakers were peeling off like hungry mouths and he ate dirt as though it was nothing. But something about him called to me. It wasn’t like the crushes other girls had. My body didn’t feel light; it felt heavy. My mind trapped, winding around him like a python. Until the day he kicked a dog in the ribs and it ended. Just like that.

My mother knew immediately. She saw it in my eyes, the glassy sheen of obsession lifting. “I hoped it had skipped you,” she said, shaking her head. “It’s a sickness, you know. Your grandmother had it too.”

I tried to fight it, to pretend I was normal. That I could look at people the way others did—momentarily—and then move on. But every few months or so, I would latch onto someone. A teacher, a stranger on the bus, a girl I served coffee to. I had to know things about them. And I couldn’t stop until they showed me who they truly were.

The first time I understood the gravity of my condition was when I got stuck on Ash. I was thirteen, and she, fifteen, a friend of my neighbour Teo’s. She had a boy’s haircut and dressed like a randomised computer game character—brightly coloured vests, striped socks, neckties as arm bands and belts. She was a diabetic and carried a bag of jelly beans in her fanny pack. The sound of them rustling would announce her arrival.

“Why her?” I would ask the stuckness, which I couldn’t so much as see but feel, a pair of firm hands that pressed on my chest and stomach, willing me closer and closer. She didn’t hide her sickness, she seemed proudly strange and spoke very loud, always smiling, even with bad teeth that should’ve been shackled in braces. Surely there was nothing more to know.

Touch, it said one day, as I carefully drew lead pencil portraits of Ash in my maths textbook, wired from a night of restless dreams about her. Touch. It applied pressure to my insides that made my hands throb and eyes bulge. I had no choice but to bike to her house.

The sun was setting when I arrived. I found her eating microwave pizza on a plastic-wrapped couch in the lounge in front of The Simpsons’ flicker and fade. “Oh. Hey kid,” she said, wiping her mouth with her sleeve. She always seemed tense when it was just us two at Teo’s, when he went to the bathroom or answered the phone, shuffling an inch or two away from me in increments.

“What are you doing here? Are you with T or—” Before she could finish, I walked to her with purpose and flopped onto the couch, so close that our legs pressed together. As though puppeteered, I placed my head on her shoulder. I could smell her skin—onions and three-in-one shampoo. She was silent, her joints locked into place, rigor mortis. As our breathing fell into sync, I slowly lifted my hand and placed a finger over her lips.

She stayed frozen for almost a minute. Then, she gently welcomed me in with her teeth, like a good dog accepting a treat. “Show me” I said, when I felt the warm touch of her tongue.

She grabbed my face and kissed me, hard, manoeuvring my head left and right. I liked her this way, prince-like and strong, radiating a genuine sense of control that her forced sense of humour and attention-seeking tendencies masked in the real world. She pulled away. Raked her hair back with her fingers. We sat there for a bit, until she muttered a few sentences so erratic and circular about me needing to go, I could only assume that she was having a panic attack. I biked back, warm air fluttering against my cheeks, a sensation something like an itch radiating through my crotch. I felt clear for the first time in months. I was unstuck. I never spoke to Ash again.

Most of the people I got stuck on turned out to be pretty harmless. Disappointingly boring, even. My history teacher Mrs. Truong secretly dreamed of being an actress and kept scrapbooks filled with yellowed cut-outs of Elizabeth Taylor under her desk. Teo’s older cousin Max, who called us little shits and went around doing petty crime with a group of tracksuited hooligans, liked to feed the ducks bread at the park every day and helped old ladies carry bags to their cars at the shops.

Then, a string of bad experiences in my late teens gave me the conviction to fight the impulse once and for all.

There was Hank, the 47-year-old store manager of a supermarket who presented himself to me in a pink diaper and asked if he could relieve himself while I watched. Then, Brianne, a girl from my year 11 English class who was funnelling money out of her brain-damaged, bedridden mother’s bank account to buy drugs and lingerie. Worse still was Diego, a boy I met at the skate park who wanted to cut me with a Swiss Army knife while we fucked and film it for his friends online. This is going to get me killed, I thought. I will beat it. I’ve got to.

🩸

I hadn’t been in love with anyone I was stuck on until I met Jack. I’d had a good run my entire first year of university—no sticking to be seen. I was studying literature and creative writing. My condition had exposed me to such an extreme range of people and situations, it had rendered me quite the storyteller.

Jack thought so too. He was my fiction tutor. Detroit born, a short man in his early thirties, with prematurely silvering long hair and a tight, muscular ass. He rode a motorcycle to campus each day and was working on a PhD about sexual repression in Victorian literature. The first time I saw him standing outside a classroom ushering people in, I felt like my chest had been defibrillated. Then, the sticking started. Invisible tentacles, swirling slow from the starving pit of my soul, wrapping themselves around his limbs, trembling with need.

It didn’t help that he thought I was brilliant, scheduling extracurricular meetings with me in his supervisor’s office to run through lists of prestigious overseas graduate programs he’d insist I apply for. I wanted him like an animal; to claw his back and lick his face, bury my head in his armpit and inhale deeply. But he was boundaried and careful about our relationship, outright ignoring me in group workshops when I’d raise my hand so as not to show favouritism; lending me novellas and albums he thought I might like, but not replying to my emails confirming that I indeed did.

He was exactly who I needed to quit. For him to drop his mask, reveal his vile extremes, or even banalities, would be a worse torture than staying away.

I unenrolled from Jack’s class just before the census date. As I clicked through the online form and saw a confirmation email pop up in my inbox, something wretched in my stomach. A spiky fierce pain that nearly knocked me off my chair. I took a deep breath, steadying myself, and went to lie down on my bed. Before I could reach my room my whole body was seized by something unseen, as though knotted in large ropes, my breathing constricted. It dragged me, with force, friction burn on my heels, all the way to the front door, slamming me into it with the force of a car crash. I slid down to my knees, ribs feeling broken, an open wound gushing hot blood above my eye. On hearing my wails my mum rushed from the kitchen to find me lying foetal. She sighed. “It’s a sickness, alright. A damn sickness.”

“What was that?” I croaked, blood pooling at the corners of my lips.

“You can’t hide away. You have to let them show you. Each one.” She went to the freezer and grabbed a bag of frozen peas, returning to hold it to my face.

“Can’t I make it all stop?” I asked, tearful.

“Sort of.” She pursed her lips, a faraway look in her eyes. “When the one that you’re pulled to shows you themself, when you feel ready to turn away, to move onto the next, you have to stay.”

I was confused. It seemed too simple. “That’s it? It won’t hurt me like that? And it won’t all keep happening with others?”

“Yes,” she whispered, leaning in closer, “but there will be something else. I can’t explain it. You will have to decide.”

🩸

Physical proximity isn’t necessarily what feeds the stuckness. Over the next year I exchanged tight smiles with Jack across campus, the occasional email. He was awarded his doctorate and went back to the states. But a dedicated routine of poring over his social media profiles was more than enough fodder to stay tethered. Posts congratulating literary peers on the publications of their “fucking transcendant” books of poems, grainy digicam photos of him playing bass in a punk band from ten years ago.

I crafted elaborate scenarios when I masturbated, penetrating myself with my fingers on all fours to the accompaniment of imagined conversations between myself and Jack. Whenever I lost myself in pleasure and meandered away from the version of him I ventriloquised in my head, I’d be paralysed by pain; shooting through my spine or setting my arms on fire.

“I will find him” I told the mounting pressure in my chest when it doubted my devotion—when an attractive stranger smiled at me at work and I blushed; when I was engrossed in my studies with childlike wonderment—“I will make a plan.”

When I told my mother I was travelling to America over my mid-year break to “visit Disneyland with my friends who were here on exchange,” she simply nodded, silently whisking a bowl of eggs in the kitchen. “You have to find out what it’s like for yourself.”

I prepared fastidiously for my trip to Detroit. I had my friend Aaron, a comp sci major, comb the living hell out of the internet for any mention of Jack that might hint at the nefarious hidden self I’d be contending with. But nothing shocked or scared us. The most revealing relic we came across was a painstaking ode to an ex-girlfriend commented under a compilation of shoegaze music on YouTube. I sent Jack an email letting him know, plainly, and without fervour, that I was going to be in his city.

I didn’t even watch any movies on the plane. I couldn’t risk being taken by a flight of fancy, charmed by Ethan Hawke waxing lyrical in Before Sunrise, straying from my path, aggravating the stuckness. Through the entire first leg, my stopover at LAX, all the way to the sticky seat of the airport cab that reeked of cat piss, I maintained a monk-like focus. Applying fresh eyeliner in the reflection of my phone screen, I asked the driver to take me directly to the dive bar I knew his friends were playing at.

Sat on a stool in a venue damp and dark as a shut mouth, I watched a sparse crowd punch, kick, and jump with abandon in front of a group of thirty-somethings known as “Spastic Fissure.” My eyes drifted to the twitch of the bass player’s taut pecs. My arm was yanked back with an audible crack, nearly knocking me off my seat. I slapped my cheek to steady myself. A bartender wearing a trucker cap with a beard dip-dyed blue looked at me, dishevelled, my duffle bag on my lap, with genuine concern. He filled a glass of water from a murky jug and set it in front of me. “Listen kid, I’m not going to ID you, but don’t act the fool, okay?”

Then, I saw him. He pushed open the door of the smoker’s section, drunk and pocked with sweat, his arm around a guy in his mid twenties with a face tattoo. Then, he saw me. He let go of his friend and stared. I saw the blood leave his face. His eyes widened, narcotic and mad. He looked like me. Getting stuck.

He moved towards me, slowly shaking his head in disbelief, mouth popped lightly open. He plopped onto the stool next to me and we sat in silence for a while. Then he looked up at me and smiled. He stroked the back of my head, tenderly, slow. “I didn’t realise it would be so soon,” he said. I felt my eyes well with tears, exhausted. He took my hands in his and I felt the relief of collapsing into bed after a hard day. He pulled me close. He stunk of alcohol. “Do you want a beer before we go back to mine?”

Snap. A cord cut. Posture straightening. Windscreens wiping. Lucidity like a church bell through city traffic. An effective stranger squeezing my palm, searching my eyes hungrily, to fan a certain waning flame.

I laughed, delirious from the jet lag, barely covering myself with a fake cough. Was that really it? It seemed on the nose. Hadn’t I always known, subconsciously at least, that in spite of our shared interests, his at least somewhat genuine belief in my work, that this was a creepy old guy who deep down just wanted to fuck me? I smiled, “I don’t need a beer. How far is your place?” He grinned. “Ridiculously close,” he chuckled, grabbing my bag and hauling it over his shoulder.

He led me through a curtained doorway to the right of the stage, up a set of concrete stairs and down a dingy hallway lit by stuttering fluorescents. He fumbled for the key and unlocked a door with a dirty French window. It opened to reveal a room full of cheap metal bunk beds that stank of weed and instant coffee. Its only accoutrements were a filthy Persian rug, a small desk holding laptop and vintage typewriter, and a yellowing Goodfellas poster tacked to the wall.

“T-Bone, the guy working the bar. He’s letting me crash out here real cheap,” he said, unlacing his boots and patting the space next to him on the bottom bunk. I had mentally prepared for my story to end with me locked in a dungeon unconscious. Skinned like a cat. My gut pinched with a new panic. I’d have to find out for myself.

I’d never had sex with one of my fixations after getting unstuck. He unbuttoned my shirt and I felt my vision blur. Then I was watching myself from further than space, flopping dead like a doll, replying in platitudes to his admissions of having wanted this so, so bad. My cunt was dead numb; kissing him was like pressing against cold meat. Each thrust pulled me further and further from life as I knew it. Levitating. Some half-human creature, subsumed by a tranquil black shadow.

🩸

My mind is quiet. Arm’s length from my thoughts. Hi thoughts! Sometimes it takes me a moment to realise they are mine. There’s a ringing in my ears that nullifies the chatter of the bar. I serve regulars and randoms with the same polite and impersonal smile. Cheeks suspended on two hooks. They all look the same, I can’t tell them apart. Aliens, shaved cats. Clone servants of one dark and humming hive. Sometimes I forget my name when they ask me. I laugh. It sounds like we’re all underwater. I am so tired. It’s like I can’t get down the air. I might faint. Who cares. My reflection in the mirrored glass behind the booth seats is featureless too. When I wipe down the surfaces in the early hours of the morning alone, I tug at my skin, rubber sex doll skin. Doesn’t change. Or, too tired to notice it changing. I bend like a reed in his hands. “My sweet, shy girl.” But shy is necessitated by nervous. I don’t feel nervous. Or angry. Or happy. Or blue. I’m amoeba-like. Drifting and drifting. I think that I’m free.

Isabella Venutti is an Italian-Australian copywriter, journalist, and editor based in Naarm, Melbourne. With bylines in Refinery29, Polyester Zine, and Mixdown Magazine, as well as short fiction featured in Baby Teeth and Demure, her work often delves into the intricate dance between illusion, ego, and self-perception— particularly as it manifests within the arts.