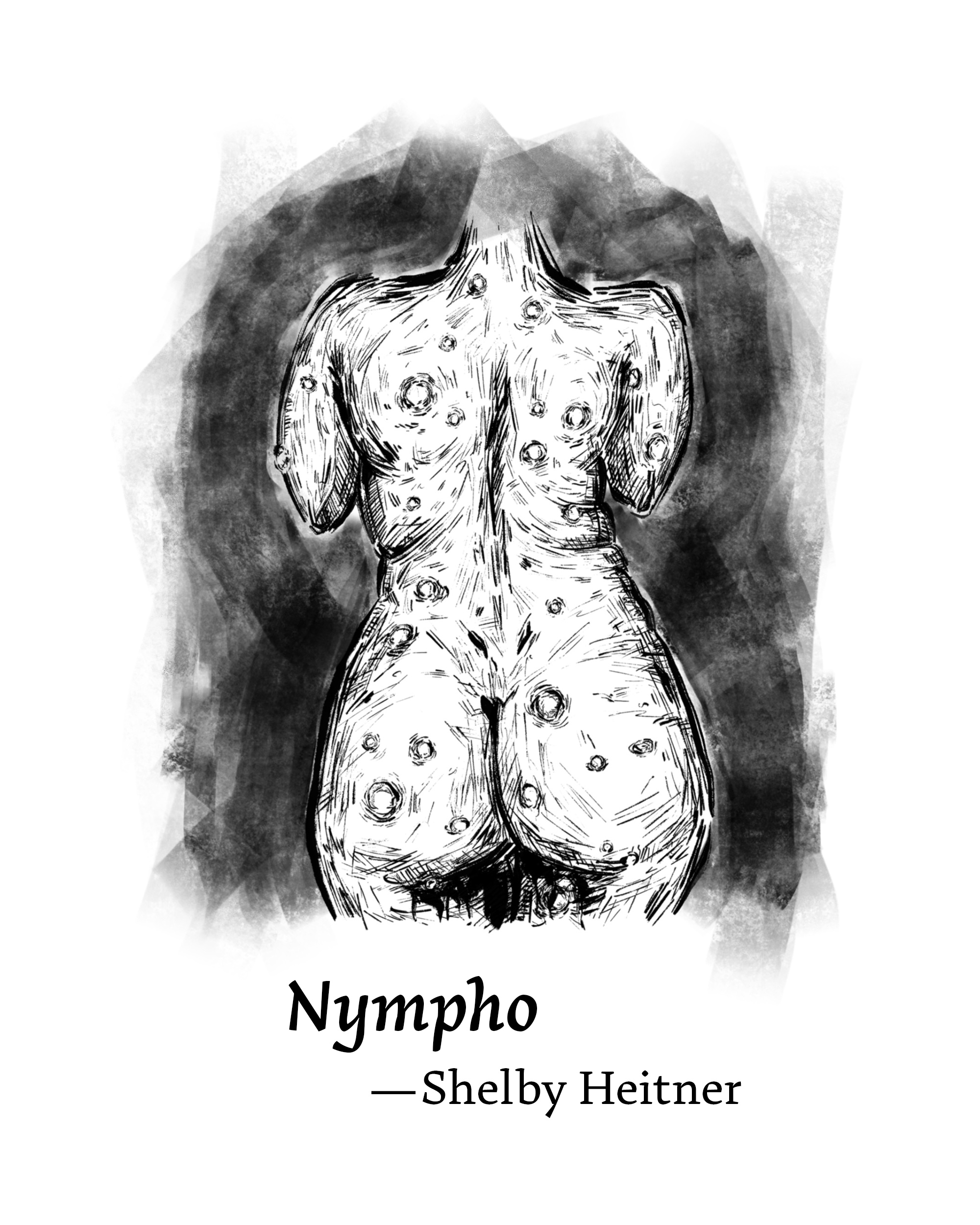

Nympho

It was the first time I’d ever lived alone. I wanted to go as far away from my old life as possible, which turned out to be a small studio apartment in Bed Stuy. In my housing search, I prioritized speed and price, which made me happy up until the moment I got out of my mini U-Haul and realized there was no chance my beloved leather couch was going to fit through the front door.

To my friends, I called my new place The Armpit. Technically it was a “garden-level” unit, which, in non-realtor speak, means basement. The Armpit was an illegal sublet; the real renter was taking a year sabbatical to study the effect of climate change in Mumbai, but since her unit was rent stabilized, she didn’t want to give up her lease. A friend of a friend of a friend knew the renter and connected us via email. The pictures made the place look dark and small, but it was very cheap and close to the subway. I said yes right away.

The pictures the renter had sent me were more or less accurate. The front door was down an uneven flight of stone stairs that lead from the quaint, tree-lined street to my sub-basement. There was very little natural light, save for one large window that overlooked the building’s trash bins. Quite the view. I couldn’t smell the refuse, thankfully, but even with my bed pressed up against the far wall, I could sometimes hear the sound of rats gnawing through plastic at night. I tried to clean my apartment the best I could – I went through gallons of windex, bleach, and even an ominously opaque container of Iodophor disinfectant – but no matter what I did, a warm dampness always hung in the air, like a foggy bathroom after a particularly long shower. After a few months, mold the color of raspberry lemonade encrusted all of the bathroom tiles. I tried to scrub it off with a toothbrush, but the bristles turned pube-like, so I gave up.

In general though, I was happy enough. Only half of my furniture was Ikea. I didn’t have a TV, which made me appear both broke and cultured in equal measures; the truth was that I watched all the same mindless manna on my laptop anyway. The men I brought back from app dates never seemed to notice any of my apartment’s apparent decay, let alone mind. I have always believed that I could show up with chicken pox and as long as I kept up my routine of yes, yes, oh god, yes, they’d never notice.

I noticed my first welt about six months after I moved in. I was making an entire box of pasta, which I planned to ration out in forkfuls to last a week. I started temping at a recruitment agency a few weeks before, and was still relying on my savings for rent and food. As I tipped in my De Cecco, I noticed a flat, red circle on the inside of my wrist. Without thinking, I put down the pasta box and scratched it. The welt’s color quickly saturated from pretty princess pink to crimson. I scratched it again; I’ve never had any self control. After a few minutes of itching, I poured my boiled penne through the colander and resolved to ignore the welt.

As with anything you deliberately try to forget, however, for the next hour I thought about it obsessively. It wasn’t until I’d eaten my pasta dinner and started watching an episode of The Office on my laptop that I eventually stopped scratching.

A few days later, I caught myself rubbing my back against the pole of my clothing rack while I was getting dressed for work. I went into my bathroom and stood backwards on the lip of my tub so I could get a good view in the mirror when I turned around. Sure enough, there was a blotch the size of an angry quarter right above the waistband of my pajama shorts. I itched it. I got off the bath and checked my wrist deliberately for the first time since the pasta incident. There were three little dots now where the one had been. A tiny ellipsis. I grabbed some black eyeliner and drew a line between them, connecting them up like a little constellation. I licked my finger and rubbed the eyeliner off, which felt nice, but wasn’t as satisfying as scratching.

Julia was the first person I told about the welts. We had met four years earlier through my ex-boyfriend, Adam. Julia was a music scout for RCA and had briefly dated one of the other men in Adam’s soccer league. I liked Julia immediately, which was not a given with Adam’s friends’ girlfriends, believe me. Julia had untamable curly hair, like I did. Julia cared deeply for others, but had little tolerance for nonsense. She wasn’t the type of person I would invite to a movie screening on a random Wednesday night, but she was the one I got wine with when I got fired or broken up with. I suspected many people felt this way about her.

I called Julia up and we met at a dive bar a few blocks away from my apartment. I’d heard from my deskmate at the recruitment agency that the place had a good backyard. It was the beginning of spring; too cold to sit comfortably outside, but we did so anyway, aspirationally. There were little wooden tables and twinkling fairy lights that illuminated graffiti of anime girls and anthropomorphic animals.

Over our little tea table, I pushed up the sleeve of my black puffer and unfurled my arm, careful not to knock over our barely-sipped IPAs. I shook my wrist at her. “See?” Julia grimaced and made a gesture for me to put it away.

“I think it’s stress hives,” I told her.

“Poor baby,” she said. “You and your psychosomatic illnesses. Are you under stress?”

“What do you think?”

“I mean it’s been six months.”

“My body speaks for itself,” I said.

Julia took a long sip of her beer. Lacy froth decorated her upper lip. She licked it off. “You should see a dermatologist.”

“I’m both too old and too young for insurance,” I said.

Julia agreed. Three of her college roommates from her old Burlington co-op had recently posted barefoot engagement pictures with their hirsute partners. “Everyone needs health insurance. They’re all freelance feminists until they realize the tax benefits of conformity. Next thing you know, they’ll be having little hairy babies that I’ll need to pretend are cute.”

I forced a laugh.

Julia looked at me and winced. “Sorry.”

“It’s fine,” I said. “I can talk about it.”

She shrugged, and twisted a lock of her curly hair around her pointer finger. “Your body speaks for itself.”

We continued to drink our beers and the conversation drifted to other things. I was glad Julia didn’t press. As she knew, I had been pregnant and now I wasn’t. It was a surprise. I’d dated Adam for seven years when he knocked me up. He was almost ten years older than I was. We’d met on an app the summer after I graduated from Kenyon. We went on a few dates before we became exclusive: art museums, Shakespeare in the Park, that kind of thing. I think Adam was attracted to me because I retained and recalled unexpected facts, which he interpreted as intelligence; I was still young enough to remember what I’d learned in college, and was able to flex that to my advantage.

Adam’s parents lived in Greenwich, Connecticut and liked chino shorts and pickleball. They thought of me – and my job as a pottery instructor – as a phase. Even though Adam and I weren’t ready to get married, we decided to go ahead and have the baby. Adam had a fancy job as a venture capitalist for educational startups. We lived in a West Village apartment that was full of chrome and clean lines. We had the space; we could afford it. Why not?

We told no one, not even our parents. My breasts largened. I felt entitled to open seats on the subway. Adam came with me to all the appointments, laid out large, oblong pills next to my morning OJ. Calcium. Folic Acid. Vitamin D.

Three months in, just as I was beginning to show, I was taking a shower before work and felt a deep loosening near my hips. It was as if someone had delivered the final twist on the screw that held up my insides. An unburdening. I looked down and saw thick ribbons of blood spooling out of me, dancing around my feet as they swirled down the drain. My vision turned staticky and my tongue thickened; I knew I was going to pass out. The next thing I remember, I woke up in a shallow bath filled with water the color of my own blood. The color of my baby. I was screaming.

That night, Adam and I sat in bed. I had a towel wrapped around my wet hair like a turban and was wearing a postpartum diaper to catch errant blood. Adam wouldn’t look at me, and kept reading a stupid scifi novel on his Kindle. I stared out at the blankness of our space. We had a professional cleaner come in every week; Adam called her for an emergency visit that afternoon so she could erase every trace of our child from the tub.

We sat like this for who knows how long, saying nothing until Adam finally put his Kindle down and turned off the lights. His arms groped at my sides and he pulled me into himself so we were two nested commas. I worried that my diaper would rub against his leg. There was a hot wetness on my neck and I realized he was crying.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I’m so sorry.”

“I am too.”

“No no you’re not,” he said. “Not like me.”

I didn’t have the energy to tell him what I should have, that no, I wasn’t sorry like he was because I was the one who lost a fucking child, who had it forcibly ejected from my body, a feeling he could never understand. Instead, I asked him what he meant.

“I’m relieved,” he whispered. “I know I’m not supposed to be, but I’m so fucking relieved.”

We broke up four months later. It wasn’t about the baby, but to me, it was all about the baby. Everything was. At that point, I’d stopped working, having given up all of my shifts at the pottery studio. I spent whole days eating Ruffles in my pajamas; I liked how their salty ridges dissolved into flatness on my tongue. Our relationship bumbled along for longer than it should have, Adam too guilty to break up with his ailing girlfriend and me, too empty to do anything but continue. It ended tearfully and without sex. Julia let me stay on her couch until I found a new apartment. Adam paid for my movers and let me keep whatever I wanted. I couldn’t make enough money to afford rent as a potter, so that’s when I started temping.

After my beer with Julia, I became even more convinced that if I ignored the marks, they would soon go away. This flew in the face of all logic – especially as the number and frequency of welts were increasing daily – but made sense to me. I was twenty-nine and healthy enough. I’d already had chicken pox. Whatever it was, it couldn’t kill me.

During that time, I developed a few coping behaviors to ameliorate the itch. I bought over-the-counter calamine lotion and dotted little white circles on top of all the red ones three times a day, as directed. My desire to itch never really faded though, only lessened, and I had trouble resisting the temptation to scratch. In between my hives, I now had track-mark-like streaks running down my arms, illuminating my preferred scratch patterns.

In order to sleep through the night without waking up to itch, I also started taking Benadryl. Two pink pills and a swig of water. Later I upped it to three. It knocked me out, but left me swimming each morning in the medication’s syrupy haze. It was a miracle if I could get out of bed, let alone get myself ready for work. The medicine made me want to sleep forever in its warm hug. I stopped brushing my hair and neglected my laundry for so long that everything I wore had been excavated from my hamper strata. I didn’t have the energy.

I called Julia again during week four, while inspecting my naked body in the mirror. I counted sixteen spots on my arms, a few on my inner thighs, and two big ones on my chest. I was like a human twister board. “I’m so itchy,” I told her. “I’ve doubled my dose of Benadryl and I still can’t sleep through the night.”

“Poor baby,” she said. On the other end, I could hear the slick clicks of her moshing computer keys. “Hold on,” she said. “I’m Googling this.”

“Maybe it’s black mold,” she said. “Maybe you are allergic to mold and the spores are in the air and you are ingesting them in your sleep and breaking out.”

“l think it’s mosquitos.”

“You are on the first floor,” she said. “Are you seeing any mosquitos?”

“Well, no. Maybe one. I definitely killed one on Tuesday.”

“What about bed bugs?”

I tore myself away from my image in the mirror and walked over to my sleeping alcove. I loved my bed, even though it was a hard mattress and the free boxspring I got with it. Still, the sheets I used were soft – a high thread count set I’d pilfered from Adam – and I’d added a camel-colored cashmere throw that used to be draped over our sofa. I felt safe when I was in my bed, and I hadn’t seen any bugs. It couldn’t be that.

“I don’t think so,” I said finally.

The other end of the line was silent.

“I sent you a link,” Julia said. “Call them, then we’ll talk.”

She hung up. I swiped over to my messages app and saw that Julia had sent me a link to an NYT profile on the Bed Bug Magician. Larry King (no relation), the bed bug magician, was a Wall Street trader turned exterminator. Bugs, Larry said, are recession proof. The profile detailed how Larry lost his job as an international commodities trader after the crash in the winter of 2009. After two months where he tried to become a Hollywood screenwriter, he sold all of his suits and bought a bed bug detection dog for 10k.

In the article’s photos, Larry looked neither like a magician nor a Wall Street trader. He reminded me more of the guy who haunted my local bodega and drank forties out of a paper bag. Still, I was desperate. I swallowed my pride and called his hotline.

A woman picked up with a voice like red-lacquered nails. “You got the Magician,” she deadpanned. “We make your bed bugs disappear.”

I explained to her about my bumps, and how even though I was really really extra positively sure I didn’t have bed bugs, I wanted a check just in case.

She quoted me a price of $350. I laughed from the bottom of my soul.

“No, really,” I said.

“Really,” said the Magician’s assistant. She said the price of the inspection would be deducted from my treatment cost, should I need it. I checked my bank account and swore.

“Still there?” she asked. I told her yes. My mind was elsewhere, thinking of Julia giving me one of her stern, motherly glares. I made the appointment. After I paid, I would have twenty-three dollars left in my bank account.

The next day I took sick leave from my job and waited for the technician to arrive. He came around 10. When I heard him knock, I ran out of bed to let him in. The dog handler was a chubby man with dreads that drooped down to his horseshoe belt buckle. Behind him, he rolled a mesh wheelie suitcase with a whimpering dog inside. I ushered him into my apartment as quickly as I could, praying that my landlord, who lived upstairs, wouldn’t see and start to get suspicious.

The tech took one look at my apartment, then put on a surgical mask and shoe covers – the same kind that doctors use – over his sneakers before unzipping the pup. A beagle, maybe.

“Can I pet him?” I asked.

“No,” said the handler.

The dog sat patiently at his ankles and let out a curt yip.

“Miss, could you please wait in a different room?” He said. “Your presence is making the dog very uncomfortable.”

I agreed, also feeling very uncomfortable, then realized that leaving the room posed a particular challenge in a studio apartment. In the end, I stood in the entryway of the bathroom and watched the little pooch sniff around my apartment. He trotted around the radiator and kicked lightly at my refrigerator with his paw.

When the beagle got on my bed, he started to ferociously dig, like a toddler at the beach trying to get to China.

“Yeah, you got ‘em alright,” said the tech. He reached into his fanny pack and excavated a dusty, bone-shaped treat. I walked over to the bed and glowered at the dog as he chomped, profiting off of my own misery.

The dog handler explained to me that officially, he knew nothing about bed bugs, only dogs, but unofficially, he thought I’d need three treatments, each one week apart. I should call the office to get a quote. In advance of treatment, all of my clothes, books, paintings, and other personal effects would need to be packed up in airtight plastic boxes or trash bags. They would stay that way for the duration of treatment, so I should pack a suitcase to live out of as if I were on vacation. I should also continue to sleep in my bed – a thought that repulsed me – because the bugs were attracted to the CO2 I expelled and would thus follow me around the apartment no matter where I was.

There was no way I could afford one, let alone three, treatments, but to get the handler to leave, I promised I would call the office later that day. I could tell he didn’t quite believe me, but mercifully, he said nothing. He packed up his pooch and left, letting in the smell of rotting compost from the bins outside before he closed the door.

I laid one of my used bath towels down on the lounge chair I’d gotten to replace my sofa, a gesture more performative than beneficial, sat down, and pulled out my laptop. I googled ‘bed bugs,’ ‘what to do if bed bugs,’ and ‘self extermination bed bugs.’ I toggled to the image search section first, and admired the array of fleshy backs, children’s hands, and bulbous limbs, all mottled with the same dots I had. When I was sated with my share of gore, I read articles from WebMD, the EPA and the Cincinnati Department of Health. They all said basically the same thing: without treatment, I was fucked.

At the point in which someone was getting more than twenty bites a night (which I was), the population was growing exponentially. Every day birthed new little nymphs that were thirsting for their first blood meal. I read on, even though I shouldn’t have, about how in sex, adult male bed bugs forcibly overtake the females, cracking through their exoskeletal thorax and injecting their sperm through traumatic insemination. The women were left with a leaking wound, increased mortality, and a cadre of fertilized eggs. The pictures I saw looked just as grizzly as it sounds.

I closed my computer and wondered if anyone had ever died from an untamed colony of bed bugs. More and more nymphs would be demanding more and more food, and I only had so much to give. I thought about calling my Dad. He was still in Ohio, where I grew up, working as an ophthalmologist at the Dayton VA. He’d been in that job for the last thirty-two years. It was a stupid idea to call him. We didn’t talk often and if we did, it was never about personal things. My dad was a bootstraps guy. His idea of advice was telling me to deal with my problems “head-on.” My mother had been the bridge between the two of us, and once she died, there was nothing but chasm, not even animosity. Fiscally, we were also severed; my dad had made it very clear that I was cut off after I graduated, just like his Dad had done to him. Still, however misguided my impulse was to call, I knew it came from the same place where small children tug on the wrong woman’s skirt in the supermarket, a yearning for security from a person who could tell you that everything would be alright and you would believe it.

I called Julia instead.

“Was I right or was I right?” she said when she picked up.

Upon Julia’s instructions, after we hung up I went to the Target in Downtown Brooklyn. She’d Venmoed me some money – a loan, we called it – so I could buy all the supplies I needed: pillow protectors, double stick tape, lysol spray, Cimexa. I’d made a list while I was on my computer earlier, but I’d forgotten to email the list to myself so I’d have it on my phone. I tried to remember everything I’d written down as I careened my large red cart through the aisles, throwing the items in haphazardly without looking at the prices.

When I got home, I left my packages by the door, unopened. It was after eleven now and I was exhausted. I warily approached my bed. My sheets were rumpled from where the dog tread earlier, but I couldn’t bring myself to smooth them. A place of comfort now perverted, the bed repulsed me.

I took a deep breath. The first night, I reasoned, was bound to be the hardest. I needed to get it over with. I changed into pajamas, letting my old clothes pool beneath me, and got in bed. I tucked the top sheet beneath my chin like my mom used to do when I was a little girl. I counted my breaths, trying to block out the images of little bugs crawling all over me, babies and adults, suckling my delicious blood. Eventually, I was able to forget myself and got carried away on the undertow of sleep.

I woke up the next morning at eight. This was very unusual as I considered myself a night owl and would often sleep until the late afternoon when I had days off. Clearly, I’d underestimated the mental strain my lack of a diagnosis had caused. It was a relief to finally know what was wrong with me.

I spent the next hour opening my Target packages and preparing my battle station. I outfitted my vacuum with a crevice tool, giving it a little vroom-vroom to test. I unboxed my new steamer, which would kill the eggs that were too small to get vacuumed up. Then, I dressed myself tactically – socks tucked into sweatpants, a turtleneck shirt, a mask– to leave no skin exposed. It was time. I took a deep breath, stripped my sheets, and flipped my mattress.

Even though I knew, cognitively, what would be there, I was completely unprepared for what I saw. There was an entire colony of bugs: little baby nymphs, clear clusters of translucent eggs, and fattened, frolicking females. The tableau reminded me of the gingerbread cities my mom used to make. Before she died of esophageal cancer, my mother was a librarian and would set up her cookie miniatures in the lobby every year at Christmas time. It was a kluge of a city, with large skyscrapers nestled next to quaint churches that were all dusted with a powder sugar snow. A battery-powered train puffed along plastic tracks, swirling through cotton candy trees. Little gingerbread mothers held the hands of their little gingerbread children. The display would stay up for six weeks or so, until the cookies cracked and the icing sugar sagged. My mom would take one building home that I would get to eat, and the rest were thrown away into black trash bags to decay further out of sight.

As soon as I made this connection – to the gingerbread city, to my mother – I felt a tenderness toward the bugs that I couldn’t quite explain. They were trying to feed themselves and their children. They were trying to survive. I wiped my hand along the mattress, letting one of the fat black bugs crawl onto my finger. It was a female, I thought. The bug moved quite quickly, waddling down the back of my thumb and onto the palm of my hand. I had to keep twisting my arm to keep it in view. Was there really such a big difference between us? I ate meat to survive and she ate me. If anything, I was worse, since I killed other animals while she made me itchy.

After a minute or so, the bug stopped moving in the web between my index finger and thumb. I didn’t feel her latch, but I could see her thorax begin to expand. She was feeding. As I watched her eat, I felt like I had been taken advantage of in some way. I ran into the bathroom, and put my hand under the tap. The bug struggled against the cyclone of sink water, her tiny legs pumping in the surf, but ultimately she relented, and disappeared down the drain.

I looked at my hand and saw the beginnings of a welt bloom between my fingers where she had fed. I had, intentionally, been avoiding the mirror over the last few weeks. It wasn’t productive, I told myself, to dwell on what I couldn’t control. But I could control the bugs now, if I wanted to. I dared myself to look.

I undressed and stood on the lip of the tub to get a better view. I was surprised. The three dots had faded from my wrist, but many more constellations had taken its place, a full night sky of angry stars. I had so many marks that from a distance, it looked like I was badly sunburned. I ran my fingers along the topographical map of my flesh, cataloging the bumpy red mountains from fresh bites and scabby valleys from blood meals long passed.

I began to cry. Since puberty, I had always been critical of how I looked – my thighs were too big, my hair too poodle-y – but now, as I regarded myself in the mirror and was forced to confront my new ugliness, I could finally accept that I had once been beautiful. I felt like a middle aged woman, who found herself missing the catcalls she used to despise. But I was worse than invisible now. Look at what they’ve done to you, I told myself. You need to kill them and if you can’t, pay someone else to.

I stalked around my apartment, looking for my phone, and found it underneath a pile of dirty clothes next to my refrigerator. Out of charge. I waited a painful five minutes until the Apple logo illuminated the darkness of my screen. Against my better judgment, I called Adam.

My first call went straight to voicemail; I knew from experience that he screened all his calls this way. I tried him again, and a third time. On the fifth call, he picked up. I could hear the tinny sound of coffee shop music pulsing on the other end of the line.

“Adam! How’s it going?” I tried to sound light, buoyant.

“We said we wouldn’t do this.” He seemed upset, his voice was low and serious, but I detected a note of concern that I could warp to my advantage.

“I know,” I said, “but I’m in a bad way.”

“A bad way how? Are you drunk? You sound drunk.”

“No, I’m not drunk, Adam,” I said. “I have bed bugs.”

“Oh.” A pause. “That sucks.”

“It does suck,” I said, indignantly. “I’m going crazy. I’m itchy all the time. They’re in my clothes, in my hair… I can feel them crawling all over me. It’s like I’m being haunted by a colony of invisible vampires.”

“I’m sorry to hear that, Alice. I really am, but it’s not a good time right now. Mitch and I are on our way to a client meeting.”

I thought about all of the skinny, pretty people of Adam’s world, wearing pant suits and teetering in too-high heels. They pointed resolutely at drab slide presentations while boardrooms full of powerful men clapped and purposefully wrote things down on legal pads. They all seemed so perfect, so clean.

“I’m going to go,” Adam said.

“No, wait!”

I could hear him breathing on the other line.

“I know I’m not good at this,” I said, “but I really need you right now. Please. Five minutes.”

“Okay,” he said, reluctantly.

I could feel him waiting for me.

“I need some money,” I whispered.

“You… what? I can’t hear you.”

“I need some money,” I said, louder, too loud, as I absently scratched at my arm. “I’m illegally subletting my apartment and need to pay for the bed bug treatment myself.”

There was a long pause on the other line.

“Are you working?” He finally asked.

“Yes.”

He sighed, breathing a loud wave of static into my ear canal. “I need to think about it,” he said. “I’ll call you.” It sounded like a lie. We said our goodbyes and he hung up.

I waited for a week for Adam to call me. In the meantime, I called in sick to work. Since I was temping, I only got five days off for illness a year, but the thought of going back to the office, looking how I did, was inconceivable. I could make it, I reasoned, rationing pasta until the money from Adam came through.

By day three, I managed to get the courage to actually vacuum up the bugs, but instead of throwing out the vacuum bag in the outdoor trash immediately, as was recommended by the internet, I opened it and picked the nymphs out of the dust with a spoon, depositing them into a mason jar. They were almost always alive when I dug them out. Through the clear glass, I would watch them scrabble, fuck, shit, and hide. Every day, the glass grew more and more full. It was a whole ecosystem, powered with my blood.

I probably would have continued this way for some time, if I hadn’t woken up one day unable to see. It is a strange sensation to wake up this way. My mind, at first, couldn’t comprehend that I was in fact awake and it was morning. Once I realized this was not a dream, I made a guttural noise, closer to a choking than a scream. I’m blind, I thought, the bugs have made me blind.

I flailed my arms and legs to throw off my covers and fell, as gracefully as I could, onto the floor. It probably took me five minutes to navigate across my small apartment, but I kept crawling until I felt the coolness of my bathroom tile under my hands. Slowly, I quested my arms out, trying to locate myself in space. I found my bath on the left and the sink on the right. I stood up slowly, using both hands to grip my sink’s porcelain love handles.

Carefully, I peeled open an eye with my fingers. The intensity of the sunlight shocked me. Stimulus overload; I shut it again.

I took a few moments to mentally prepare myself then pried open the other eye, this time relieved to see my bathroom just as I had left it. Dappled sunlight stretched its arms through my streaky mirror. All of my lotions and potions were strewn around the room, crusty and unused for many months.

I inspected myself in the mirror. I’d had a few face bites before, but always around my temples. Now, it looked like a few bugs had had a picnic right below my lashline, leaving a mountain range of welts that swelled my eyes shut. I looked like a boxer who’d gotten the worst end of a bout. This was ridiculous, I realized. This couldn’t go on. I needed to leave.

I called Julia. I felt bad, burdening her again with my problems, but I felt I had no one else to turn to. Julia was on her way to a yoga class and seemed happy, albeit surprised, to hear from me. She thought since she had diagnosed the problem, it would have been taken care of by now. I lied and told her I had been going to work, saving money for the three necessary treatments, but in the meantime the problem had gotten out of hand.

“Please,” I begged her. “I can’t stay here. I feel them crawling all over me all the time.”

I could hear her drumming her fingers on her phone, thinking. “One night,” she said. “I’m serious. Bed bugs are the herpes of New York and I’m not catching.”

I thanked her profusely, then fled to her apartment as quickly as I could.

When I got to Julia’s place in the Lower East Side – a swanky co-op above Essex market that’d been gifted from her father – I could hear the velvety tones of Radiohead leaking out of her door. I knocked. The door opened a crack, enough for me to see Julia’s wild hair. An arm shot out holding a garbage bag. I took it and the door closed again.

“I need you to strip,” Julia said through the door. “Bed bugs can travel on clothing.”

I shifted uneasily, remembering the last time I had taken my clothes off in front of the mirror. That was a week ago and in that time, I’d undoubtedly gotten even more bites.

I considered telling Julia that I forgot something, my wallet maybe, and then I’d leave and never come back. But leaving meant returning home to The Armpit and surrendering myself to another night of the bugs. Slowly, I took off my clothes, layer by layer, until I was standing in my underwear. I was down to my last few pairs, the ones with the stretched out elastic and the discolored cotton lining. I wasn’t wearing a bra.

“Okay,” I said. I stood like the Birth of Venus, stoically covering my bits. “I’m ready.”

Julia opened the door, but didn’t step into the hallway. She let out a guttural noise that sounded like the beginning of a Come in! that was aborted half way through. I watched as her face melted into a mixture of pity and revulsion then looked down at my naked, hairy toes.

“Poor baby,” Julia said. “How did you let it get this bad?”

I didn’t know what to say. Since my mother’s death, I had always sworn to myself that I would never let anyone see me in a state of physical decay. And yet here I was, desperate and naked, entirely exposed.

During my mother’s last few months in homebound hospice, she specifically requested that I go away. She wanted my memory of her to be of happy times, like our family camping trips to Marblehead or the late nights she spent reading me Dickens and Tolkein aloud by lamplight. I knew my mother’s wishes came from a vein of altruism – she wanted to hide her suffering from me – but at the time I believed they were incredibly misguided. How dare she take away my last days with my dying mother, even if she was said mother? I was fourteen and so I dealt with her decision in an age appropriate way: I yelled and screamed and slammed my door countless times, which had the unintended effect of undoing any chance I had of staying after all. After a week of arguing, my father determined that I caused too much stress and I was sent to my paternal grandparents who had retired in Boca Raton.

My grandparents lived in a retirement home there, which everyone navigated via golf carts that they decorated for the major holidays. It was always sunny in Boca, which gave me the distinct impression that I was existing outside of time. My grandmother, a kind woman who always had orange lipstick pooled in the corner of her lips, dragged me everywhere she went to try to “keep my spirits up.” My weeks were thus filled with sulking next to her while she played canasta in the card room and sulking behind her at the driving range. I believed that I was closer to death there than I had been at home.

After a month or so, in an effort to get me to socialize with “kids my age,” my grandparents signed me up for a class at the local pottery studio, but the next youngest student was a forty-two year old second wife with blue hair. Still I went, eager for any time alone to brood. With my headphones in, I took my anger out on innocent piles of clay while I blasted out my eardrums with New Order and The Clash.

In her last few days, my mother was completely morphined up and so my father gave me the option to come home and say goodbye. I took it. Since I’d been away, our house had been transformed into a mini-ER. My mom was set up in a hospital bed in the middle of the living room for easy access. Long tubes carrying drippy liquid sneaked the floor like telephone cables and there were mini trash cans full of used diapers and half-eaten mushy food.

I don’t remember what my mom looked like, but I do remember the smell. I was hit by an overwhelming miasma of decay and rotten flowers. I ran outside into our front lawn and threw up in a potted fern. I wished I had never come home. I stayed the rest of the week with my friend Sarah from school. My dad called her house four days later and told me that my mom died.

I looked up at Julia again now, her face devoid of love, but filled with pity. I grabbed my clothes off the floor and ran down the hallway. I had expected her to call after me, but she didn’t. Her door clicked closed in an almost melancholy way.

Clothed again, I took the L-train home, curling myself up into a ball on one of the seats, hoping that no one would notice me. When the Q train ran above ground between the boroughs, I admired the sky, rosy and streaked golden with stretch marks, before we plunged into the bowels of Brooklyn. Back at my apartment, I checked my phone and saw that I had a text from Adam. It was long and used proper punctuation. Not a good sign.

A-, he wrote, Sorry it took me so long to respond. I needed to think deeply about what you asked me and consider all the implications etc. etc. of my decision. Ultimately, I still feel responsible for you and your well-being, but I’m not sure it’s a good idea for me to give you money right now. I’m worried it will encourage an unhealthy dependence between us instead of letting us heal independently. Upon reflection, a big part of why our relationship fell apart was your lack of resilience and self-reliance. I’m sorry about your situation and even more sorry that I wasn’t able to help in a meaningful way. x Adam

Fuck you, I wrote back. Did you have your therapist write this for you?

I didn’t expect Adam to respond, and sure enough, he didn’t. I tore through my apartment, beelining to the Benadryl bottle in my bathroom even though it was only eight PM. I took three pills, washed them down with a slurped handful of tap water, then took two more. I paced back and forth across my room, waiting for the medicine to kick in. When it did, I knew my muscles would leaden and my mind would slow. Finally, I would sleep.

I don’t usually remember my dreams, but I did that night. Actually, I’m not entirely sure it was a dream at all. A Benadryl hallucination, maybe. Regardless, it was the first time I’d dreamt in third person, seeing myself from the outside. I floated above my bed and watched my body, Alice’s body, twisted up in her creased sheets.

It was a strange sensation, this untethering. At first, I wasn’t convinced that she was really me. I decided to test it. I willed myself to move my arm, and was amazed when I saw Alice’s arm below me move as well. Coincidence, I thought. I stuck my finger in my mouth. Alice did the same. I put the wet finger in my ear. Alice did the same and when she did, I could feel a dampness inside my ear canal.

She – I mean me – was so beautiful, I could hardly believe we were the same person. Unlike me, this Alice had no bites. Her skin was as clear as a freshly frozen lake. As I watched her, I felt the blossoming desire, cresting and falling, but generally trending upwards towards pleasure. I began to touch myself, slowly at first, and then faster.

As I watched Alice come, I realized she was moving on her own without me. I felt nothing. No release. The link between her and my incorporeal self, I realized, had been severed. How? Why? My room slurred with an extreme vertigo. I began to fall. I was sand slipping through fingers. Water seeping through cloth.

I hit the floor with a loud crash. A broken mirror, my mind fractured into a million consciousnesses. When I came to, I blinked up with a million eyes. I was crawling between apartment molding, burrowing through orange insulation foam, nestling down to sleep in the cavities of screws and in outlet sockets. I was within a colony of thousands just like me, bugs in every state of decay, marshaling their reserve of blood until the hunger for more grew too much.

Suddenly, I felt my antennae twitch. My brain rushed with a dizzy intoxication; there was a strong smell, sort of like ylang-ylang. I peeked out from my spot in the wall. Other-Alice was in her bed a few feet away, bathed in a preternatural glow. A soft aura of blue particles orbited around her restful body. As other-Alice exhaled a soft snort of sleep, the blue mist deepened into the color of the sea. I watched it fade into the color of a cloud, Alice puffing blue life into the mist again with her next breath.

Like a line of soldiers, we scurried across her floor, up her wooden bedpost, and into the soft cocoon of Alice’s bed. The blankets were heavy, like avalanched snow, but I borrowed through them with all of my strength until I saw the milky cleanness of her skin. I latched, and began to suckle tenderly on Alice’s chest. Her blood tasted like rose petals and moonlight. I swelled as it rushed into my body. She didn’t feel me as I ate her, so sweet and so warm.

It didn’t take me very long to get full. I withdrew my beak from her skin, and watched the very beginnings of a welt begin to form where I had fed; it was a hickey of sorts, a mark of my uncontrollable love. It made me happy to know she had something to remember me by.

When I was done, I crawled back through the delicate folds of Alice’s sheets and the lightness of her moon-lit room into her warm wooden bed frame. Bugs crawled upside down above me, next to me, on top of me, worse than the train at rush hour. Feces were smeared on every surface in large Jackson Pollock strokes. It stank of rotten meat and, inexplicably, like sweet raspberries. I heard mothers, forcibly ejecting their eggs, moaning throughout our camp. Little nymphs, barely after a first feed, clustered together in corners for protection from the tumult. And everywhere, everywhere, there was sex. A giant orgy. Women on their backs crying in pain, men squealing with delight.

And suddenly I was on my back too. I flailed my legs vigorously in every direction. I cried, but no one heard me over the other hundreds of cries. I tried to turn my head, but I couldn’t. A sharp searing pain on my side, I let out a roar. I tried to reason, beg, plead. Nothing worked. I hurt everywhere now, in every part of my body. I managed to turn my head, just enough, to see another woman right next to me spitting out the same curses.

My bug captor finished, dropped me, and crawled away. I splayed out on the wood, unable to stand. The other bugs ignored my prone body and scuttled over my back. I was exhausted, relieved. I would have to do this every day, I knew, again and again for my children.

I woke up unsettled and itchy. The bitter taste of shame had faded in my mouth and I was now nauseated with guilt. I got out of bed, drank a glass of water, and compulsively checked on my mason jar of bed bugs that I’d saved from the vacuum. I’d hid them underneath my sink so the bugs didn’t have to get any light. They are nocturnal creatures after all.

The jar was three-quarters full, its glass foggy and spotted with excrement. Unless I looked closely, I couldn’t differentiate between the bugs. Mothers, nymphs, babies, they’d morphed into one undulating mass. I held the glass jar on my wrist and watched them rave against each other, agitated and wanting, trying to bite at a skin that they couldn’t reach. It wasn’t fair, taunting them like that. I had so much I could give them, so much that I didn’t need.

I put the jar down and unsheathed a kitchen knife. I’d never done this before, cut myself. The blood began to gurgle out from my wrist faster than I had anticipated. I tried to catch it in a bowl. When my vision began to fuzz at the edges, I wrapped a paper towel around my arm and secured it with duct tape.

Over the sink, I unscrewed the lid and poured in the contents of the bowl. A few bugs escaped, but most crawled back in to get a sip of my blood. The bugs writhed, scrambling frantically on top of each other, their color lightening to a brilliant red as they drank. I watched the jar for a while until from somewhere far away, I heard a light knocking.

“Alice?” A voice called. “Alice, are you there? We’re going to come in now, Alice.”

I tried to say no, but I couldn’t make my lips move fast enough. A wave of bright sunlight washed over my body. I scrambled away on all fours, hiding my face with my hands.

After my eyes adjusted to the light, I peaked out from between my fingers. Adam and Julia were standing in the doorway. They were so perfect and so clean, like a plastic couple atop a wedding cake. I was struck by the fact that it was the first time I’d seen Adam in months. He was dressed in gym clothes, wearing sweatpants with his company’s logo down the leg. When I knew him, he had long hair; now, he kept compulsively scratching the back of his crew cut.

As Julia and Adam moved inside, I saw another man standing behind them. I recognized him, but only vaguely. He was wearing plastic sunglasses on the back of his head and was carrying something that looked like a fire extinguisher.

The three of them stood side by side and surveyed the room. I looked around with them, seeing my apartment as if through their eyes. I noticed the little piles of clothes I’d left everywhere that were blackened with dirt and sweat. The stacks of unwashed dishes, caked in rotting food. The pink mold, which had begun to spread from the bathroom tile into the kitchen.

I heard Adam retch, and saw Julia elbow him in the side. The third man, the one I didn’t know, coughed and said, “Yep. That’s a bad one.”

Adam whisper-shouted to Julia, “It’s not a good sign if he’s saying it’s a bad one.”

“Please,” I said. “Please, go away.”

“We’re worried about you, Alice.” Julia’s voice was calm and patient. “We brought The Magician. Adam and I are going to pay. We’ll help you get all cleaned up.”

“I’m going to make ‘em disappear, Alice. Don’t you worry.”

I let out a scream, deep and primordial. The sound opened like a gash deep inside me. “Don’t touch me,” I seethed. “Don’t touch my babies.”

For the first time, everyone stopped and looked right at me. Julia ran up to where I was cowering by the refrigerator, her arms outstretched as if for an embrace. I regarded her coldly. I’d warned her not to touch me. The skin on her hands was milky and blemish free. She reminded me of other-Alice. I bit her.

Julia cursed – FUCK – and then, as if bewildered, she said “I’m bleeding. I’m actually bleeding,” as she cradled her hand. Adam rushed to Julia’s side and put his arm around her. “We should go,” he said. Julia glanced back at me, but then she nodded, and let Adam steer her outside, back up to the street. When they’d left, I laughed and spit on the floor. Good riddance.

Then I heard a psst-psst sound coming from the other side of the room. I’d been so distracted by Julia that I’d forgotten Larry King. He had goggles on and was spraying something with his fire extinguisher. My eyes began to water and burn. I clawed at my face, trying to wipe off what was stinging, but it didn’t help. It wasn’t a fire extinguisher, I realized, it was poison.

“Please stop,” I begged him. “Please stop.”

“I gotta do my job, little lady,” he said. “I got paid to do this. Don’t you worry.”

I began to cry harder, my acid tears burning as they rolled down the bites on my face.

I held my mason jar of bugs against my chest and rocked back and forth. “Shhhh,” I whispered to the jar. “Shhh. It will all be okay. We’re going to be okay.”

Shelby Heitner is an MFA student at Brooklyn College and the Fiction Editor for the school’s literary magazine, The Brooklyn Review. Her writing has won contests at the New York Times and Lincoln Center. She also makes YouTube videos about art and culture on her channel @twentysomethingcritic.