Demonyo

Soon after my lola died, my body started changing in unexpected ways.

My mom said it was because of the stress. In the hour before Lola’s funeral, while my ate was zipping the back of my black mourning dress, I noticed new patches of hair on my arms—dark, silky rolling fields over my brown skin. When I ran a hand through my black mane, I found new curly strands hidden at the nape of my neck.

I thought nothing of it, but then at the church where Lola’s body was stuffed in a plain casket, where my cousins and titos and titas were sobbing through the teary obituaries and the specialized sermon, I felt an unfamiliar throb of pain in my stomach, just below my navel.

I hurried to the bathroom, feigning a grief-induced breakdown, doing my best to hide that I was about to piss my pants and vomit at the same time. In the toilet bowl, I left swirling red streams and bloody clots the size of black slugs. I stared, unsettled for a moment, then flushed my first menstruation down the holy pipes of God’s house.

“Fuck,” I said.

Later that day, I found out that we Filipinos had superstitions about funerals. We didn’t believe in going straight home, as it carried the risk of bringing stray and angry spirits into one’s living room. So instead, we indulged in a great feast to celebrate a dead one’s life. The meals were plentiful—titos, titas, and family friends ordering frivolous plates of salty seafood and fried rice from the local Chinese restaurant.

But I could eat none of it.

I hunkered down in one of the bathroom stalls, clutching my stomach, watching my hands grow pale and clammy. Had my nails always been so long? Had my limbs always been so lanky? What of my tongue, then? Why did it have the sudden ability to stretch past my chin?

My lola used to tell me about the women in my family having terrible puberties—of hair growing wild, of chests growing tender, of stomachs cramping so painfully they felt like they were turning inside out. I always thought that my puberty would be different, but now my lola was gone, and it seemed I was turning out just as she said.

Someone entered the bathroom, their heels clattering against the mucky tile. I heard my mom’s aggravated voice. I thought she was looking for me, so I stuffed my underwear with a wad of toilet paper and pulled it back on.

“. . . a heart attack,” my mom said. “That’s what everyone thinks.”

I peeked through the crack and saw she was on her phone.

“She died, anyway, before she could give The Talk to her apo.” My mom crossed her arms. “No, no, I won’t have any other story. It’d be such a disgrace.”

The word “disgrace” followed me like a latched and feral spirit all the way to bed that night. It rumbled inside my chest, taking shape, making my cramps grow shard-like teeth—gnawing, gnawing away at me. As happens to all eleven-year-old girls, I felt that my body was quietly rebelling against the adults around me.

It just wasn’t right.

Lolas were supposed to die of cancer. Old age. A lethal fall down the stairs.

The police that came to my house last Sunday morning had told my mom everything: my lola died playing mahjong with the Devil.

My mom, then, didn’t cry. She simply put her head in her hands, muttering a Tagalog prayer I didn’t recognize. Me, I was hiding around the corner.

Lola was found with her head detached from her body, the police had said, and she was still holding her rosary.

Ay sus, my mom said. Oh, Jesus.

Would you like to press charges? the police asked.

It’s no use, my mom said. She was fucking that demonyo. She died in love with him, too.

My mom made sure the funeral came and went without a word. Once the lie of Lola’s death-by-heart-attack rooted itself firmly within my family, I found myself in her old room for nights on end. All her belongings were as they had been: her sewing supplies in an old cookie tin, her nightgowns ironed and hangered, her wigs and makeup scrambled along her vanity.

I stared at myself in her mirror. A gauntness had overtaken my cheeks. I rifled through her drawer, looking for something to cover the dark circles.

What I found instead was a jar filled with a yellowish juice. Labeled: embryos. Empty. It stirred a dribble of drool along my lip. An involuntary slithering of my thin, stretchy tongue. A warmness, a longing in my gut.

Behind the container was my lola’s bible. I’d never really seen her read it. It was heavier than I thought; on the table of contents, Lola had scrawled the address to the rickety chapel down the road of our suburb, as well as a local phone number. I tore out the page, stuffed it in my trainer bra, and tucked the book safely away.

My mom found me soon after.

“What are you doing?” she said. “You shouldn’t be here.”

“What’s with the jar?” I asked.

She hung at the doorway. Her eyes passed over the empty bed, as if she were expecting Lola’s ghost to be hunched there, sewing up a pair of jeans. “Don’t touch it.”

I began to unscrew the lid. “What’s The Talk?”

She stomped through the threshold, grabbing the jar, then ushered me out. “I don’t know where you heard that.”

I was about to tell her about my first menstruation, but I stormed to my room instead. She wouldn’t understand. She wouldn’t comb the knots out of my hair like Lola did. She wouldn’t sing me to sleep, nor would she kiss my forehead and tell me old stories until my eyes fluttered shut. She wasn’t Lola, and ever since Lola’s death, I just wanted her back.

I locked myself in my room and called the mysterious number from the bible page. It rang a few times, then a deep voice croaked from the other side.

“Yes?”

Without seeing its face, I knew who it was. I hung up immediately and held up the thin paper, tracing my finger over Lola’s handwriting—once, twice, until I memorized the cursive looping of her a’s and b’s.

She was known to easily succumb to offers to gamble—a vocation, she called it. An addiction, my mom would say instead. Of course, I knew of Lola’s gambling far before my own mom did. I even knew about her Devil boyfriend, but she said I wasn’t allowed to meet him. The hour before her very last game, the one that ended in her beheading last Saturday night, I remember catching my lola hobbling toward the front door, her heels in one hand and a folded wad of money in the other.

“You need to be more careful when you’re gambling,” I had told her.

“Para kang nanay mo.” You sound like your mother. She gave me her gap-toothed smile.

“Don’t worry. When the girls in our family become women, we become stubborn hags. We defend ourselves just fine.”

I remember sitting on the stairs, clutching the wooden white railing. “Are you sure, Lola?”

“You’ll understand. You will, soon enough.” She looked me up and down, clicking her tongue.

“You poor thing. It’s time I tell you . . . Wait for me to get home, and I’ll tell you a story.”

I don’t remember her face. I just remember the night cicadas screaming just outside the front door. That was the last I ever saw of her.

The next afternoon, I took my bike and the address and went to the chapel by myself. I didn’t have a plan, I didn’t even have any bullets. I just had a confession: I was thinking of killing the Devil.

When I arrived, it was seemingly abandoned, probably the least Catholic church I’d ever been to—devoid of ornate stained glass and extravagant gold, filled with saint statues left to erode. The only light came from the small windows alongside each aisle, leaving the inside of the church a murky gray.

I thought of my lola taking her last steps down the aisle of weathered pews, clutching her rosary in her right hand. I thought of her neat gray wig, her tiny figure, her manicured hands tapping each mahjong tile before her last game began.

I walked up the aisle and heard voices burbling from the sacristy. My stomach began to ache again, almost excruciatingly so. Though the bleeding had stopped, I had been cramping for days after. I heard it was normal. Being a growing girl means being familiar with pain.

In the room behind the altar, I found a crowded folding table. Men and beer mingled around the porcelain tiles, puffing out smoke from their cigarettes and reeking of their sour drinks. When I entered, they turned, smiles crawling up their faces.

The Devil was the only one with a clerical collar.

He was stouter than I expected. He was the age of a lolo, with wrinkled brown fingers and a row of tiles in front of him. If it weren’t for Lola’s blood on his hands, I would have thought he was an innocent old crone. Looking at him, at his void-like eyes, I felt a craving, like I could pick his bones clean.

When he welcomed my lola in, what kind of words had he used? Were they tender? She never favored forceful words. Had he, instead, pressed his hand to the small of her back? My lolo used to do that to her, and the hard lines in her face would always melt away.

“Kid,” the Devil said, his deep voice slicing the silence apart. “How can we help you?”

“My—my lola,” I said, because I could not say anything else at the moment.

He crossed his arms. “Which Lola?”

“You.“ I swallowed. “You killed her.”

“I’ve killed many Lolas. Remind me, which one is yours?”

I clenched my fists at my side. My stomach lining began searing, and my vision grew dark. I wheezed out, “She carries a pink plastic rosary. She loved you.”

The Devil nodded. “Teya.”

“Yes, Lola Teya.”

“Of course, I remember . . . I remember her head lopped off easily.”

His cronies snickered around him.

“Now, kiddo,” the Devil said, “what are you doing here?”

I gulped rising vomit. My mouth felt like paper. “I’ve come to kill you.”

More drunken laughter. More swigs of beer. Something was ringing in my ears. An old whisper, a family secret, Lola’s bedtime tales lulling me to sleep. Wait for me to get home, and I’ll tell you a story.

The men parted as the Devil gestured to the tiles and the empty seat in front of him. “There’s a rule here. If you’re in my church, you play a game.”

I retained his gaze. Saw the reflection of myself; saw how starved I was.

He asked again, “What’s your answer?”

“Go fuck yourself,” I said simply.

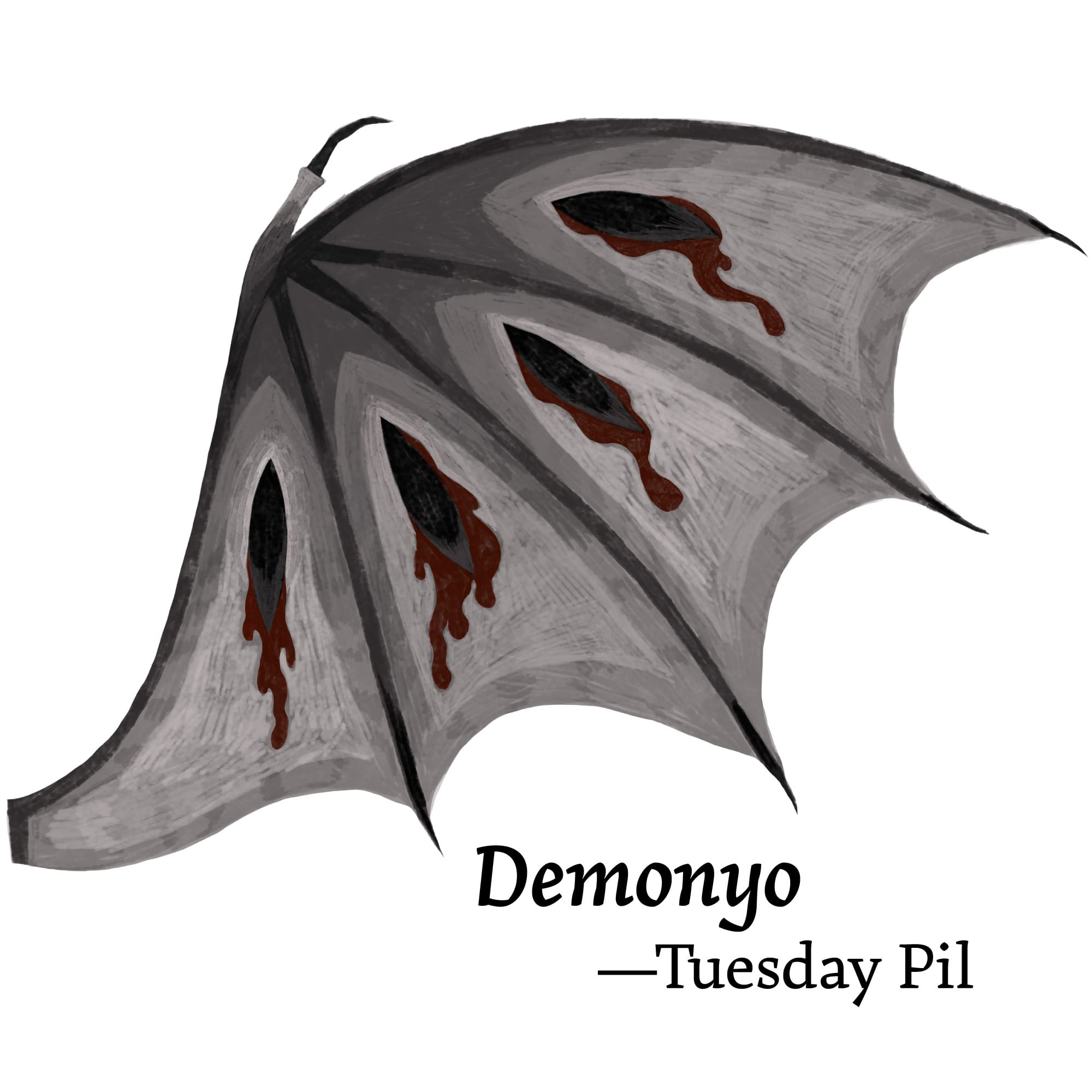

My shoulder blades twitched—slowly at first, like centipedes writhing underneath my skin—then a searing shockwave traveled down my neck to the back of my ankles. All at once, dark, webbed-like wings sprouted from the upper half of my back, tearing through the threads of my shirt.

And then my torso, spilling pink guts and swirling red streams of bloody clots, detached from my waist, and half of me rose into the air.

Chairs squealed, tipping over as lolos rose from their mahjong tables, sending tiles scattering against the hardwood. Shining metal, the barrels of small pistols, were raised and pointed at my temple. My tongue melded into a long, pointed tube, striking someone’s flesh. Silver bullets ricocheted off my pale skin, sending bodies crashing to the floor. My sprouting claws tore into the men, splattering blood across the beige walls and little hanging crosses.

When only the Devil was left, he was still sitting in his chair. He raised his thick brow, resting his hands on the peak of his belly.

“Manananggal,” he said. “You and your lola are shorn from the same cloth, after all.”

As his blood entered my mouth, I tasted sweet cherries.

Tuesday Pil’s writing features themes of anticolonialism, environmental justice, queer identity, grief, and unapologetic Filipino/Filipino-American kids that proudly exercise healthy amounts of rebellion. Born in Manila, she now resides in North Carolina. Her work can be found in Archive of the Odd (soon!), Tea Table Magazine, and The Candid Review. Details of her shenanigans and her other published works can be found on her blog: tuesdaywrites.wordpress.com. She is currently represented by her lovely agent, Andie Smith, for her middle grade novel work.

Instagram: @tuesday_writes

X: @tuesday_writes