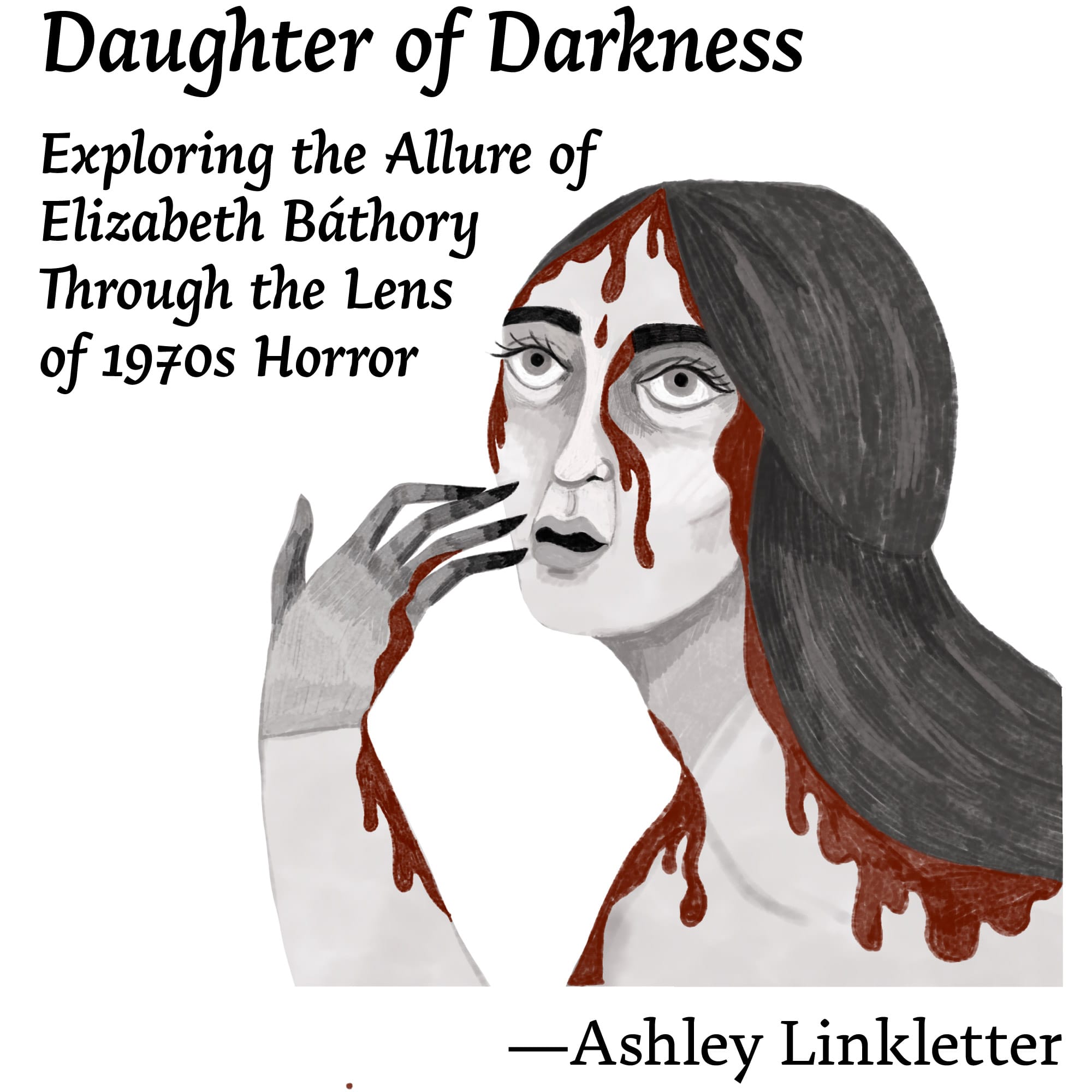

Daughter of Darkness: Exploring the Life and Myth of Elizabeth Báthory Through the Lens of 1970s Horror Films

Vampire, sadist, first female serial killer in recorded history; these are only a handful of the lurid descriptors ascribed to Elizabeth Báthory, a 16th century Hungarian noblewoman who would eventually be given nicknames such as “Blood Countess” and “Countess Dracula” (Báthory is thought by some scholars to be the inspiration behind Bram Stoker’s iconic novel of the same name). Accused of murdering over 600 people, many of whom were said to be servant girls between the ages of 10 and 14, Báthory delighted in draining the bodies of their blood and then bathing in it for the sole purpose of retaining her youthful appearance. Although the accuracy of the accusations aimed at Báthory—many of which were coaxed from indentured laborers under threat of their lives—are now being challenged by historians, there’s no denying the influence of Báthory’s ghoulish and bloody wake on popular media, particularly films in the horror genre made during the 1970s.

As a real-life monster, Báthory’s legacy and mythologization is deeply woven into pop culture and horror media. Through films, books, and television she has come to represent the Other as well as the threat of queerness and female power (as evidenced in the films discussed below). Often portrayed as a woman who will do anything for beauty and youth, including torture and murder, the evil Elizabeth Báthory is presented as a stand-in for a litany of fears or anxieties present in the 1970s and onwards.

Horror films of the 1970s had a deep well of social unrest and anxiety to draw inspiration from, with pivotal movements such as Women’s Liberation, the Civil Rights Act, the Stonewall Riots, and demonstrations against the Vietnam War shaping the genre as a whole, resulting in films that often challenged the status quo while expressing a deep distrust of authority. Unlike the monster-driven horror films that were popular prior to the 70s, this decade was fascinated with the idea of the person-as-the-monster and the psychological ramifications of evil. When working within that framework, a monstrous individual such as Elizabeth Báthory would prove to be the perfect muse.

Countess Elizabeth Báthory was born on August 7, 1560, near Nyírbátor, Hungary, a town that was, during the 15th and 16th centuries, owned by the Báthory family. The Báthorys owned everything, right down to the town’s graveyard and mausoleum. Elizabeth’s birth was the result of a union between two separate yet equally powerful branches of the Báthory clan. Among her second-degree relatives, you’ll find the illustrious Voivode of Transylvania, several Hungarian princes, a pair of Grand Dukes, and even the King of Poland. By all accounts, the Báthory household in which Elizabeth grew up with her siblings was quiet and sheltered. In the land surrounding the Báthory estate, conflict between indentured laborers and the ruling class was rampant. In contrast to this account, the sadistic behaviour she was eventually accused of has been attributed by some Báthory scholars to exposure to abuse and cruelty as a child. As with many facets of the Báthory mystery, there are multiple, often opposing narratives that might be used as attempts to condemn or exonerate her actions.

One incident that shows up repeatedly in descriptions of Báthory’s childhood is her exposure to a particularly shocking method of execution, wherein a Romani peasant was sewn up into the belly of a horse for the crime of selling a child to a group of Turks. Whether or not this horrific event actually happened is, of course, up for debate among historians, but it effectively demonstrates the type of brutality and violence that the ruling class used to dominate indentured laborers and serfs.

As a child, Báthory would have received lessons on running a large estate as well as on the art of courtly manners; she is thought to have been studious, a perfectionist, and a lover of philosophical conversation. Her educational interests included mathematics, the classics, and languages, of which she spoke Hungarian, Latin, Greek, German, and Slovak. At the age of 11, in what would be a mutually beneficial transaction between both families, Báthory was engaged to 16-year old Count Ferenc Nádasdy. When the time came for her to be married, Báthory found herself newly orphaned with a vast inheritance. By the time she was 13, she was rumoured to have given birth to a child that would later be given away (yet another matter of historical merit under dispute).

Accusations of cruelty, torture, and murder began to spread in the last ten years of Báthory’s life. As the legend goes, Báthory killed hundreds of young virgin women over a period of decades—some estimates posit over 600 individuals died by her hands. In 1612, four of Báthory’s servants, all of whom were thought to be accomplices, were arrested and tortured into making a confession before being burned alive. As punishment for her crimes, Báthory was held captive in a bricked-up tower room, where she eventually died from what is hypothesized to be malnutrition. By some accounts, she was quite literally held behind a brick wall while other reports hypothesize Báthory was essentially found under house arrest. While several burial sites have been the subject of investigation (and in spite of her infamy), Báthory’s final resting place has yet to be found.

In the introduction to historian Kimberly L. Craft’s expansive and exhaustively researched second edition of Infamous Lady: The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Báthory, Craft prefaces the letters, witness testimony, and historical recreations which comprise the book by admitting to the non-definitive nature of Báthory’s history and identity. Craft describes Báthory’s legacy as such:

On the one hand, she was a member of Hungary’s ruling elite, the wife of a national war hero, and descended from an old and illustrious noble family. On the other hand, she was a lesbian vampire witch who bathed in the blood of 600 victims whom she had tortured to death before writing about each in her diary.

Not only does the murky nature of Báthory’s life records inhibit the curation of a factual timeline, the records that we do have tell a different story about her rumored death toll. Through translations of the legal accounts of Báthory’s accomplices, Craft reveals that:

Over 300 witnesses testified, but only a handful claimed to have actually seen her do anything wrong. As for the body count, those with knowledge testified to perhaps 50 dead over a period of decades; one or two thought the count was as high as 200. In fact, the allegation of over 650 victims came only from a single source—an unknown servant girl, still in childhood, who based her entire claim on hearsay.

While working on this essay, I found myself drawn deeply into the lore that surrounds Báthory’s real and imagined life. The more I read about and researched the events of Báthory’s life, the more convoluted and decentered my knowledge and certainty around the subject became. Unsurprisingly, this experience has spilled over into my analysis of her representation in 1970s horror films. When I first began thinking about Báthory as a film subject, I wanted to better understand the way her story and her legend have been used as a trope in horror media. After watching films and documentaries, reading books, and listening to podcasts (of which I must recommend You’re Wrong About’s enthralling episode on the topic), I began to understand that Báthory isn’t a fixed story or a fixed archetype. Rather, the name Báthory exists as a form of metonymy, where a word or phrase is substituted for another word closely associated with it. In this case, Báthory has become a name with an urban legend-like history that symbolizes the scandalous or monstrous nature of female horror characters. Under the umbrella of Báthory all are welcome, especially murderers, serial killers, sadists, lesbians, and nobility.

It can almost go without saying that the films I’ve watched about Báthory are, like many forms of media inspired by the wake of her legendary life, unequivocally and unapologetically camp. These imaginary worlds, and the characters that inhabit them, are garish, vulgar, and sleazy, filled with bloodlust—and plenty of regular lust—as well as gratuitous violence and nudity. Relatively unknown but all considered cult classics, Countess Dracula (1971), Daughters of Darkness (1971), and Thirst (1979) feature various iterations of Báthory as a main character: age-fearing evil queen; world-weary lesbian vampire; victim (and begrudging leader) of a futuristic commune that houses human blood cows and conducts psychic engineering.

“Her macabre and bloody quest for eternal youth” –Countess Dracula, 1971

An important piece of historical context to keep in mind when examining both Countess Dracula and Daughters of Darkness, both of which were released in 1971, is the fact that the Hays Code was abolished in 1968. The Hays Code, also known as the Motion Picture Production Code, was first enacted in 1930. Created by a Catholic priest along with Catholic publishers, the Code was a series of moral guidelines that prohibited “antisocial or criminal conduct” from telling the story. With the abolishment of the Code, directors were given free reign to include graphic violence, nudity, and scenes of lesbianism (as is the case with Daughters of Darkness) in their films.

A veteran director for the BBC and Hammer films, Peter Sasdy’s Countess Dracula had a limited theatrical release in the United Kingdom before being released a year later in the United States as a double-feature with Vampire Circus (also a Hammer Production). This film is better summarized by its secondary, more literal tagline, “The more she drinks, the prettier she gets. The prettier she gets, the thirstier she gets.” This version of the Countess Elisabeth Nádasdy (played by the seductive Ingrid Pitt) is a mature widower and established member of the Hungarian aristocracy. At the beginning of the film, the newly widowed Countess Elisabeth discovers that virgin blood has wildly effective anti-aging and libido-boosting properties. While drawing a bath and carving a peach for the Countess, a young servant girl accidentally cuts herself, the blood from her cut splashing on the Countess’s face which instantly transforms into that of a beautiful young woman. Armed with this newfound knowledge, the Countess tasks her steward-and-sometimes-lover Captain Dobi and loyal maidservant Julie with kidnapping and killing virgins from the local village.

What makes this film particularly interesting is its binary presentation of youth and old age. The Countess either exists as her true, elderly self (which is exaggerated with warts and other prosthetics) or a false, younger self. As the New York Times review of Countess Dracula so succinctly stated, “One minute she creaks like parchment, the next she’s a Playboy centerfold.” Although the film is over 40 years old, it remains as topical as ever in its treatment of ageism, standards of beauty, and the notion of invisibility as one grows older (in fact, I was reminded of 2024’s The Substance several times as I was watching Countess Dracula).

When presenting as her younger self, Elisabeth dresses in diaphanous, jewel-toned clothing, and her mannerisms are confident, highly sexual, worldly, and flirtatious—in short, she moves through the world as a youthful young woman. Once depleted of virgin blood, she is instantly dour, moving stiffly and clothed only in funerary black. Countess Dracula might not be self-aware enough to recognize its own take on ageism, but it doesn’t make the film’s messaging, when looked at critically, any less potent. In this case, the character of Elisabeth can only thrive as long as she’s young—when the veneer cracks she’s condemned by her lovers as well as her kingdom.

During the last moments of the film, Elisabeth and her co-conspirators are sentenced to death by hanging, which is when the titular “Countess Dracula” is whispered by one of the townsfolk as Elisabeth’s final damnation. Like a fairy tale, the aged crone is ousted from the kingdom and replaced with a much younger woman. Although the film doesn’t condemn Elisabeth to execution via being bricked into a wall as Báthory is thought to have suffered in real life, Countess Dracula ends on a victorious note, wherein Elisabeth has been imprisoned by the village townspeople who are now safe from her killing spree.

“An erotic nightmare of vampire lust” –Daughters of Darkness, 1971

Directed by Harry Kümel and released in 1971, Daughters of Darkness is an entirely different beast than the fantastical fairy tale aesthetic of Countess Dracula. A dreamy, Gothic, and surreal lesbian vampire film, Daughters of Darkness is a swirling combination of art house and erotic horror. The score, composed by François de Roubaix (who was an experimental pioneer in the early electronic French music scene), features a synth-heavy soundtrack that is equal parts haunting and jarring.

In Daughters of Darkness, Elizabeth Báthory (played by smoky-voiced siren Delphine Seyrig) finds herself in a near-empty hotel in the small seaside town of Ostend, Belgium, accompanied by her lover and secretary, Ilona. Their only other companions are a newly married couple, Valerie and Stefan, who gradually ingratiate themselves with the mysterious sunlight-fearing women.

The version of Elizabeth Báthory presented in Daughters of Darkness is sophisticated, aristocratic, sexually ravenous, and—like any vampire that’s existed for hundreds of years—somewhat fatigued (as she says to Valerie, “After a while, it’ll only be the remembrance of a bad dream, and then the remains of a remembrance. More and more faint in your mind. I have seen many a night fall away into an even more endless night.”) Her style, of which she has plenty, is firmly planted in the 1930s. Throughout the film she wears red chiffon dresses and towards the end, in one spectacular scene, she wows in a floor-length dress dripping in silver sequins. This, unlike the Báthory portrayed in Countess Dracula, is a woman who is sure of her allure. The notion of power as a burden that must be passed down is reiterated by Camille Paglia in her book Sexual Personae: Art And Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson, where she describes Daughters of Darkness as a film where “evil has become world-weary, hierarchical glamour. There is no bestiality. The theme is eroticized western power, the burden of history.”

Daughters of Darkness has a lot to say about societal gender expectation. The male characters, of which there are few, are vulgar and easily manipulated (not to mention, disposed of). The character of Stefan, who represents a sort of male vigor and domineering strength, lives under the thumb of his mother—who is revealed to actually be his effeminate father. Báthory spends the duration of the film seducing Valerie, who not only eventually becomes her lover, but in a shocking twist ending, her successor after the Countess is impaled on a tree branch. Even still, when Valerie is seen as a vampire in the final shot of the film, her character speaks using Seyrig’s distinct Báthory voice, suggesting a sort of Báthorian self-perpetuating vampire legacy.

Vampirism, yet another horror concept closely related to Báthory, has close ties to the feminine experience in horror films throughout the 1970s (as seen in films such as The Vampire Lovers, The Velvet Vampire, and Lips of Blood). Like Báthory herself—who, while in possession of unfathomable inherited treasures, was removed from her home, married, and made pregnant while still a child—the vampire is a powerful symbol of Otherness. Like Thirst, the final film discussed below, Daughters of Darkness provides the viewer with a version of Báthory that is timeless, austere, and essentially alone for all of time.

“This ancient Evil is now a modern industry.” –Thirst, 1979

Falling somewhere between the shaky genre lines of horror and science fiction, Thirst was directed by Rod Hardy and released in 1979. Another film with a haunting synthesizer soundtrack, this score was composed by Queen’s Brian May. Considered an essential film of the Ozploitation catalogue (an Australian category defined by lower budget films in the horror, comedy, and sexploitation films), Thirst follows Kate Davis (played by a wide-eyed Chantal Contouri), a successful and happy single woman who has no idea she’s a direct descendant of Countess Elizabeth Báthory. Her character is kidnapped by a brotherhood of vampires who take her to a futuristic commune, where humans wear all white and are hypnotized and bled out in a barn-like setting. While comparisons to Soylent Green (1973) are obvious, I was also heavily reminded of Next of Kin (1982), another Ozploitation film featuring a lone female character in a remote, increasingly surreal setting trying to escape the clutches of multiple villainous characters.

Unlike Countess Dracula, which features a somewhat self-aware Báthory in her home castle environment, and Daughters of Darkness, which features a Báthory who knows she is Báthory (but tires of it all), Thirst features a Báthory-esque character who is entirely disentangled from her familial roots. Rather than being instantly seduced by her aristocratic past, Kate tries to escape from the commune multiple times and is eventually drugged with hallucinogens for the purposes of “psychic engineering.” Unlike our other protagonists, Kate rejects her Báthory background with every fiber of being.

Kate’s reluctance to embrace her lineage is due to one pressing issue: if she acquiesces, she will need to start wearing metal fangs and drinking blood (in this story, the vampires lack real fangs). Although the humans kept on the commune are milked for their blood through tubes hooked up to their throat, Kate must first drink from the throat of a live victim as part of a sacrificial display. It’s worth noting that Kate resists the drinking of blood through most of the movie, and only after being drugged and manipulated by the leader of the commune does she finally acquiesce.

Thirst is undoubtedly the most obvious example of the transient nature of Elizabeth Báthory as both an identity and metonymic device. Save for the connection with vampirism, Báthory’s name is only used in Thirst to draw a mental picture for the audience—her name is representative of the entire brotherhood and its actions, not her own. The characters who share her namesake in Countess Dracula and Daughters of Darkness are, to some degree or another, actually portraying Báthory. Here, the Báthory name is being forced on Kate, almost as if the identity itself is the true malignancy and not the person who inhabits it.

As I was watching Countess Dracula, Daughters of Darkness, and Thirst while simultaneously reading Craft’s book, it became clear to me, as a media consumer, that Countess Elizabeth Báthory exists as more of a Halloween villain than any sort of representation of an actual person. She’s truly omnipresent in pop culture. There’s a version of Báthory played by Lady Gaga in American Horror Story; she inspired concept albums from numerous metal bands; she can be found gracing the covers of romance novels and horror mangas alike (not to mention her many filmic renditions from beyond the 1970s, such as 1981’s Night of the Werewolf and 2009’s The Countess). But when it comes to finding factual information about her life, there’s so little to draw from that it’s impossible to come up with an accurate portrait of Báthory. Rather than confining her to the set contrasts as observed by Craft, where Báthory is either a noblewoman or a murderer, it has become obvious to me that these distinctions are ultimately unhelpful. Báthory, whomever she was, was a multifaceted individual who would have been capable of evil or kindness—or both. By extending this multidimensional viewpoint to the characters she inspires, such as with Báthory’s sensual yet bored character in Daughters of Darkness, her story may inspire more complicated, complex Báthory-like characters in films to come. Post-1970s, horror films with strong female antiheroines such Possession (1981), Resurrection (2022), Next of Kin, and The Substance have explored topics such as ageism, anti-capitalism, queerness, and gender roles—social constructs that were just beginning to be explored cinematically and openly in Countess Dracula, Daughters of Darkness, and Thirst.

Works Consulted

Craft, Kimberly L. Infamous Lady: The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Báthory.

Lexington, Ky., Kimberly L. Craft, 2009.

The End of American Film Censorship – Jstor Daily,

daily.jstor.org/end-american-film-censorship/. Accessed 21 Jan. 2025.

“Sexual Personae Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson: Umair Mirza:

Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive, Aug. 2019, archive.org/details/263791532sexualpersonaeartanddecadencefromnefertititoemilydickinson1990camillepaglia_201908/page/n285/mode/2up.

Weiler, A.H. “A Double Bill of Horror Arrives on Local Screens.” The New York Times,

The New York Times, 22 July 1971, www.nytimes.com/1971/07/22/archives/a-double-bill-of-horror-arrives-on-local-screens.html

Ashley Linkletter is a writer based in Vancouver, BC. Her poetry has appeared in APROSEXIA, Ink & Marrow, and Campfire Confessions. Her food writing has been published in numerous culinary magazines. She is set to release HORROR SNAX, an illustrated poetry zine, with her sister later this year.

Instagram: @ashleylinkletterpoet