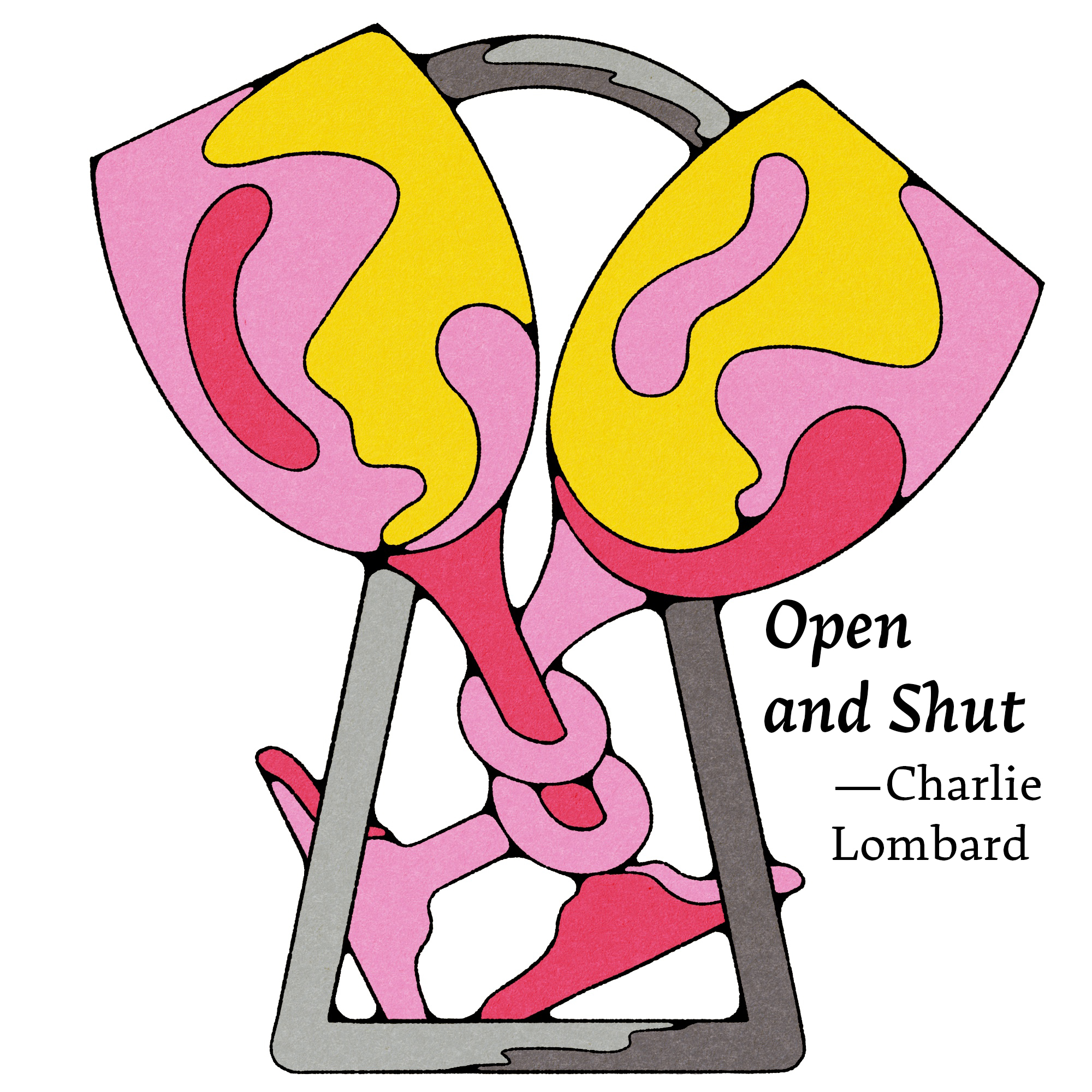

Open and Shut

We met during the deepest frost of winter, when ice crusted our eyelashes and loneliness felt like it would swallow us whole. Both of us alone in the same crowded bar. I’d only gone out to hear the conversations around me and imagine I was part of them; maybe she had as well, but then she smiled at me, and I smiled back, and by the time our glasses were empty the space between us had dwindled to none. Something settled in me, then. It had been so long since I’d done this dance. I had wondered if maybe I’d had my last.

She was an art teacher; she wanted to be an artist, but dreaming was expensive and so were oil paints. Her family was in another state, her three sisters scattered across the country, all of them too busy to visit. Winters got lonely. I think she saw in me that same loneliness, the feeling of having worlds inside you and nobody to share them with. I’m not an artist, and never was, but anyone who is alone long enough knows the pressure of a thousand untold stories clogging their throat. She spilled hers like a faucet in a house with new pipes. They were inexhaustible, each one adding bone and blood beneath her skin, giving her gravity and mass. Every few minutes she’d apologize for talking so much, so quickly, but I didn’t mind. Listening was what I’d set out to do. I’d tell her my own stories in time.

She moved in with me after two months. It was only a technicality by then; her toothbrush already lay next to mine beside my bathroom sink, some of her clothes already tucked into my dresser. She told me she hadn’t even noticed our lives growing into one another, but I’d caught her gazing fondly into our shared sock drawer more than once. We were both pretending not to know what we wanted, or where we were headed; at our age, you settled or moved on quickly. Still, we followed the standard timelines and stages. There was no rush. It was around this time that she began asking about the door. I knew she would; I knew it would be a problem from the start. It has always drawn people in, myself included, though it matches every other door on the hall. Something about the hair on the back of the neck rising, like it has a static charge. The first time I showed her through the apartment, she’d paused at the end of the hallway, testing the brass doorknob. It was locked—it’s always locked—but she kept trying it all the same. I told her it was nothing, but that wasn’t enough for her. ‘Nothing’ shouldn’t require a lock.

I am not deluded. I understand that a relationship requires give and take, the sharing of secrets and mundanities and spaces. I am also not unreasonable: she had places and things that were hers alone, and this was mine. I would share my entire life with her, open every valve of my heart for her, but not this door.

Still, I knew it bothered her. Her gaze drifted to the door constantly. Sometimes she knocked on it, as though she expected someone to answer. She would brush against it several times a day, testing.

You don’t trust me, she told me one night, that’s why you keep it locked.

I hung the key on the wall beside the door where she could see it, knowing it would taunt her, but I could see no other solution. There was no other way to prove to her how little it had to do with trust. She was pleased, but not satisfied, and I didn’t expect her to be. Without my meaning to, I had made it a test. If I trusted her with the key, did she trust me enough to stop herself using it? Would I forgive her if she did? I didn’t know.

One evening, when I returned home, I found her pressed against the door trying to look through the keyhole. I understand why, and I understood even then, but the sight of her shriveled my lungs in my chest like wet paper. I couldn’t think past the pain. She apologized immediately, repeatedly, but I tore the key from the wall, and soon we were both shouting. What’s in there that you won’t show me? What secret is so terrible?

It’s not a secret, it just isn’t yours.

If it isn’t a secret, why can’t I know? What else do you keep from me?

It’s not about that. It’s not about You.

She spent three nights at a friend’s apartment, sleeping on her couch. I stayed in the apartment alone and stared at the door and hated myself. On the fourth night, she came home with tears in her eyes. I love you. I don’t care about the fucking door. I told her I was sorry. I loved her, too. She moved back in, and although she stared at it often, she didn’t ask about the door again.

A year later, we were married. I finally met her parents and sisters, who shared her brown eyes and bright laugh. The wedding was small, wedged into the week between Christmas and New Year’s so her family had the time off. She invited a few friends. I invited less. I had no family to speak of, except, now, for her.

After the ceremony, when the reception was coming to a close and most of the guests were tumbling out into the night, her mother pulled the two of us to her table. She clasped our fingers between her worn-soft palms, asked when we would be having children, and my wife smiled at me like she was seeing the stars for the very first time. I had never wanted a child, happier to die and leave nothing behind. Still, I would have done anything to see her look at me like that again. In that moment, I would have opened any door she asked me to. If a child would make her happy, we would have a child.

We did, eventually, though at a price. Pregnancy was not easy for either of us. She couldn’t sleep because of the ache in her back, her skin stretching too tight, the thing inside her bruising her with unfinished bones. Eating made her sick, but she was hungry constantly. Her temper would flare hot and bright in an instant, and, as I fought my own desire to retreat and escape, I did not handle it well. We fought, more savagely than we ever had. I blamed the pressure put on us by her mother, the imposition of her deadline. She returned to the door.

It’s not like having a goddamn book club—it’s part of the home that we’re meant to be sharing! Are you going to keep it from our child, too?

I was—or, I hadn’t wanted to, but I hadn’t wanted any of this. I was being forced into a corner. So quickly she slipped into my life and built a new one around her. As the months began to count down, we worsened. I woke one night to an empty bed and the jingling of keys. In the darkened hallway, she faced the door in nothing but her nightdress, her hair still mussed with sleep. The key no longer hung on the wall. Delicately, tenderly, she was tracing the lock with it. I stepped up beside her and lay my hand on her shoulder, but she wouldn’t look at me.

Please, she said quietly, Just let me. Just once. As I took the key from her hands, I realized she was crying.

She let me lead her to bed and tuck her under the covers, but still she wouldn’t look at me. I wrapped myself around her, burying my face in her hair where she smelled most like sweat and herself. Already she was stiff and silent as a corpse in my arms.

The child was born red and screaming, painted with the gore of its own becoming. She held it in trembling arms, sweat-drenched and grinning at its pinched face. It clung to her finger with its entire raw-looking fist. A girl, they told me. Beautiful, perfect. I peered at the creature in my wife’s arms, and it blinked up at me with watery eyes. Almost against my will, my hand stretched to brush back the fine threads of its hair, plastered to its soft little head with afterbirth. Strands of it stretched between our skin as I pulled away.

My wife smiled at me, all tenseness between us gone in the light of her overwhelming joy. Do you want to hold her?

The nurses wiped and wrapped the child in a pale blue blanket before depositing her delicately into my hands. My daughter; shriveled and alien, but mine. As my hand supported her head—so small as to fit in the cradle of my palm—my finger slipped into a divot at the top of her skull. Suddenly there was no bone, the flesh soft and malleable as an overripe peach. I could plunge my thumb into it just as easily. The thought lodged in my brain like a splinter, uncomfortable and intrusive, and I could not shake it loose. I returned the child to my wife with shaking hands.

There was a shift when we brought the child home. The thing slept in our bed, tucked between us, and she watched it wriggle on its back like an insect. Her universe had shifted, recentering itself around this tiny thing with its pink toes and pink cheeks and pink, glistening gums. She no longer worked, having stopped when the discomfort of pregnancy became too much. We both knew I could support her, and would. Day by day, her life was consumed by cataloging the smallest changes in the child: was its hair forming ringlets? Today its eyes were darker than before, look, it smiles at the sight of us.

I wanted to feel for it what she did, this spring of adoration that welled up inside of her, but I looked at it and thought only of the rotting fruit of its skull. How strange and weak it was, with jellied limbs and a voice that could only scream. I loved my wife, but not like this; I did not know if my heart could contain all that she felt for our child. Age and strength, I hoped, would warm me to it. I was entertained when it began to crawl on its stumpy knees. She beamed at it, and at me, as though I had accomplished something through it.

One afternoon, while she slept on the sofa, I found the thing scratching at the door with sharp little nails, whimpering like a dog. I lifted it quickly away, its arms stretching uselessly toward the door. When I began walking back toward the living room and its mother, it howled like a wounded cat. My wife rushed into the hall with us.

What did you do?

I couldn’t help but bristle. She had no way of knowing how little I cared for it, had simply expected me to wound the things I loved.

God. You’re prioritizing a door over your own child, do you realize that?

It hadn’t felt like the choice I was making, but I supposed she was right. In the end, I had protected the door at the expense of the child, but it was a small price to be paid. That which is hidden hides for a reason; secrets can damage more than those who keep them. The next time I caught the child at the door, I pinched it, only once, beneath the ear. When it wailed and its mother came searching, I told her it had scraped its hand on the wood. It never returned to the door after that, though it never looked at me the way it had before.

That was the first time I lied to her, and the last. I was not always honest, but I did not lie. The child fell ill. Not horribly, but enough. She brought it to the doctor while I went to work, watching her hunched shoulders recede in my rearview mirror as I drove off. Her whole body would mold itself around the child when she held it, as though she could protect it like a flesh-and-blood cocoon.

When I returned home that night, the two were still gone. I had heard nothing from them, but I couldn’t imagine a small illness requiring so many hours of care. She answered my call on the final ring, her voice strange and flat over the phone.

Yeah, she’s okay. There’s something—they’re running some extra tests. They said some of the results were unusual, but—no, not necessarily bad. We’ll be home soon. I think. It was a few hours more before I heard the front door opening. She stood on the threshold with the child in her arms, her mouth twisted into something that looked almost painful. She would not look me in the eyes.

I’m not asking. I don’t care what you think about it. I’m opening that door. Some endings feel like they’ve been happening for years. This was one of them. I tried to take a step toward her, and she took a step back, clutching the child tighter to her chest. I couldn’t say if she thought I would physically stop her, or if she was afraid of me. Either way, I knew it was too late to repair the damage. Whatever the doctor had told her, it was enough. She didn’t wait for my approval. I watched as if through a screen as she lay the baby in its crib and retrieved the key from the wall. I heard the click of the lock as she turned it, as smooth as if it had been freshly oiled. She didn’t look back as she pulled the door open and stepped into the dark beyond it. The door slipped shut behind her.

I waited for a few minutes, just to be sure. Then I lifted the child gently from its bed, feeling its skin dimple around my fingers, and swaddled it carefully. The door sighed open like releasing a long-held breath. Behind it, the dark wrapped around the child as tenderly as its mother. I eased it shut, and the apartment was quiet again. Perhaps it always had been—always would be.

Pulling my coat over my shoulders, I returned to the bar.

Charlie is a Brooklyn-based writer and multimedia artist. They love all things unsettling, visual or written.