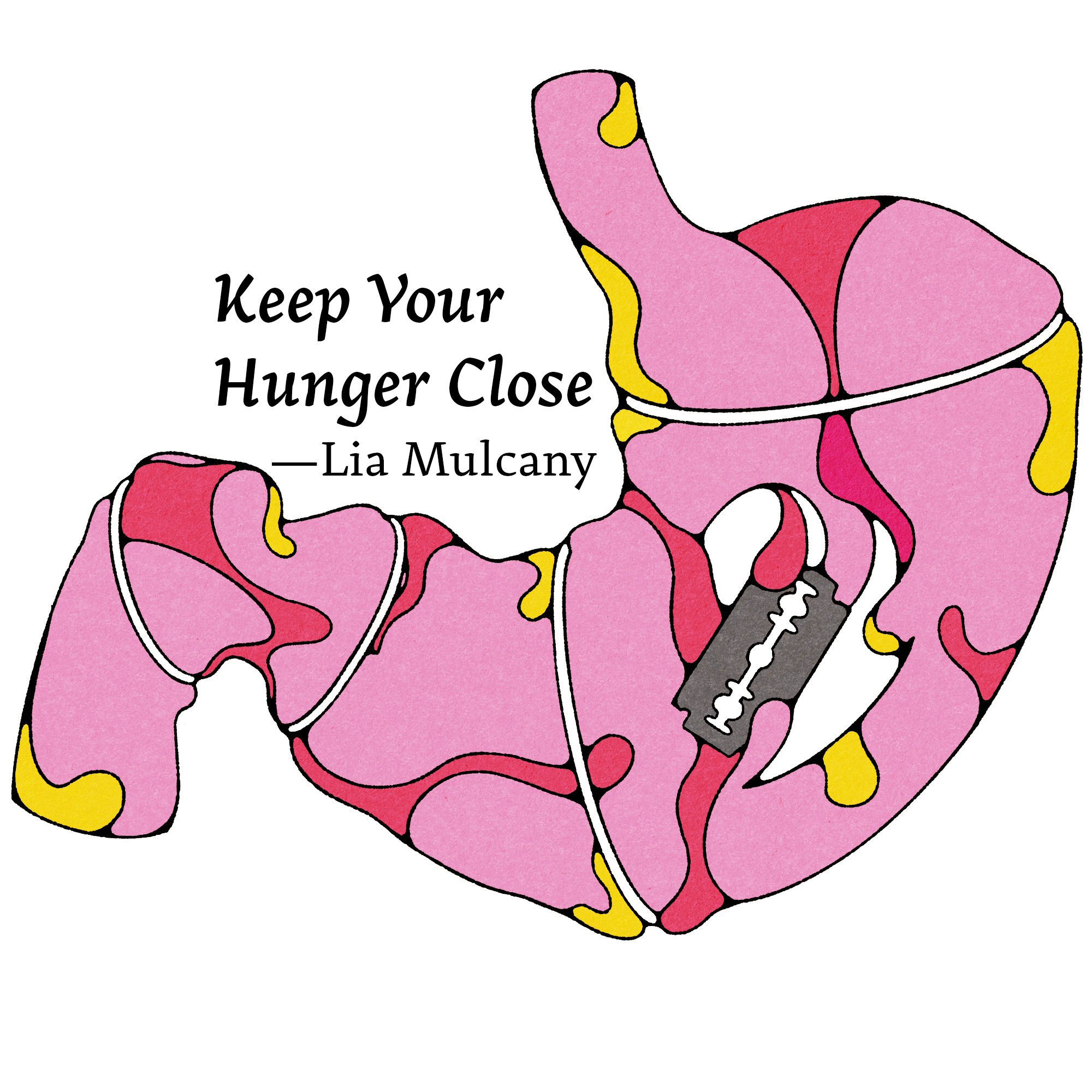

Keep Your Hunger Close

The doctor’s office stank acridly of antibacterial soap. I sat on the side of the examination table, the paper crinkling awkwardly beneath me when I shifted. It was a sunless, lifeless Monday, the clouds outside were threatening rain, and I was desperate.

Doctor Ahern, of course, was oblivious to my distress, lost in his perusal of my file. He was a tall man with a slightly frozen looking face, as though it would crack if he expressed himself too vigorously. We had known each other for five years. His wife and I went out for coffee together on Wednesdays, and I despised him with all my heart.

Eventually, he looked up.

“It’s a very common problem, you know. Especially in women.”

“I know.”

“Hmm.” He returned to the clipboard again. The paper tore a little as I bunched my hands in it. A few more precious minutes of my life ticked by, caught in this grey room on this grey day with a grey man who refused to be of any use to me.

“Have you tried the Mediterranean diet?”

“Yes,” I said, strangling back my frustration. “For almost a year now.”

I had told him this repeatedly on the last three visits. Just to be sure, I had bemoaned my difficulty with it to Frida Ahern last Wednesday, and she had made sympathetic noises and promised to mention it to her husband.

“Did you note any changes?”

I noted that I was allergic to shellfish. Nothing significant.

“I see,” he said, scratching something incomprehensible onto a clipboard. I felt an intervention was needed and leaned forward.

“Doctor. I have tried extensive diets. For years.”

I was telling the truth. I had tried the Mediterranean diet, the Volumetrics diet, the DASH diet, juice cleanses, green tea cleanses, fasting. I had tried cardio, the HIIT workout, and I could rattle off the top ten recommended exercises for weight loss and execute them flawlessly. Nothing had worked. My hunger was too great. I veered away from the strictly regimented salads and into the waiting arms of flaky pastries, caramel chocolates, sugared cakes. It was as inevitable and devastating as a rockslide.

Even darker, more desperate measures had failed me. Gagging on my index and middle fingers brought up nothing but hacking coughs and the faint taste of thin bile at the back of my throat. My disappointment tasted worse than any vomit I could have produced. And there was no way I could afford enduring the rigmarole of hospital consultations that I would need to access gastric surgery.

The man sitting placidly across me in an uncomfortable-looking chair was my last hope. I could not carry on this way. Desperate times, humiliating measures.

“Doctor Ahern—Michael,” I corrected, sweetening the name in my mouth. “You’ve been so good to me over the years, and I am incredibly grateful. Believe me, I have taken your every suggestion to heart. But I am, truly, in need of more…extreme measures to deal with this.”

“Hmm,” was all he said in response. Rage boiled up behind my eyes, but I didn’t let so much as a muscle twitch on my face. I simply smiled at him beatifically, even a little pitifully. I was the very image of a sane, rational woman who knew what she was doing. Someone he could trust. Someone he could help.

“I really do feel like this is a mental issue,” he said, and my smile stiffened. “But I’m starting to understand that won’t satisfy you.”

I had to stay very quiet, I knew. Saying something stupid—even breathing wrong—might break the spell that had settled over this clinical cell of a room, might make him dismiss me with nothing more than a psychiatrist’s referral in my hand.

Doctor Ahern sighed.

“You know, of course, that I am limited by the law as to what help I can offer.”

“I know,” I said. I tried not to let my anticipation show, but I could feel my mouth moisten with eagerness. Please. Please let this be what I thought it was.

“Hmm. Yes. Well. I understand that this is a very difficult situation for you, Ms. Reid.”

“Oh, call me Jamie.”

“Jamie, then. Frida speaks very highly of you. She has emphasised your trustworthy and discreet character. And, well, I would be pleased to help one of my wife’s friends in her hour of need.”

I bit my tongue very hard. Even for a doctor, Michael Ahern was grandiose and callous. It had not just been a mere hour of need. I had been searching for help for over eight years, and seeing him regularly for five of them. Five years of watching me break down and weep like a leaky faucet, knowing that he could fix it all with a few words, a note. My hatred sat as heavy in my stomach as undigested meat.

“I am very discreet, Michael. I promise you that.”

My tongue was bleeding. I could taste the metal on the inside of my teeth, and prayed that Ahern couldn’t see it when I smiled.

“Good. Good. Obviously, I myself will do nothing. But I can recommend you to some services that I believe may be of assistance to you.”

“You mean the surgery?”

A mistake. Ahern’s eyes flickered uncertainly. “I see you have done your research.”

“I—yes. You know I have been struggling with this for some time, Michael.”

“Indeed. Well, with a little luck, you need not struggle any longer.”

Then he tore out a piece of paper from his clipboard and handed it to me. I took it reverently, like a convert receiving communion for the first time. The cheap paper was eggshell-white and fragile as a butterfly wing.

Written on it in red ink was an address, a time, and a price.

#

The day on the note came like Christmas morning—so anticipated that it was almost sickening.

Absurdly, that morning I had worried over what to wear. I stared at my reflection in a mirror gone dusty from disuse.The sight of it galvanised me, as I knew it would.

The most frustrating thing was that I could be beautiful. The bones of something lovely were there. My mother always praised my excellent complexion, the richness and lustre of my hair.

The few dates that I have had, when searching desperately for a physical feature to comment on, usually settled on my eyes. Lovely eyes. Deep and dark as inkwells, as coal, as boot polish. It always rang insincere.

I did not stare into my own eyes. Instead I forced myself to catalogue my body unflinchingly, reminding myself why I was putting myself at risk. The soft patch under my chin that I prodded miserably at. The melted jawline that I tried to hide with the fall of my hair. I traced the grotesque swell of flesh at my stomach, an abundance of soft folded lines where there should be taut simplicity. Skin either sagging or hideously stretched. My pants dug into my flesh like rope around a leg of mutton at the butcher’s.

I could be beautiful.

I arrived ridiculously early to the appointment. I had no idea what to expect—my brain threw up a vague idea of shadowy figures dressed all in black, wielding rusty scalpels in a back-alley warehouse—but the clinic was very small and clean. The sign on the outside said Marley’s Tattoo Town and featured a picture of a shirtless, muscle-bound man flexing a tribal tattoo. Morbidly, I wondered if they’d chosen the facade of a tattoo parlour to excuse any screaming.

“Ahern referred me,” I told the scowling receptionist. “Eight o’clock?”

“Early!” she accused me sharply, in an accent I didn’t recognise. “Sit there.”

I sat and waited. I hate sitting. I hate the way my skin creases and folds at my waist as I do it, the way my calves seem to inflate to the size of Christmas hams. The receptionist munched angrily on a pack of biscuits.

“You want?” she said, thrusting the packet at me.

My hunger swelled. I took one. It was delicious. I hated myself.

The surgeon emerged at half past eight, when my anxiety was starting to spike. He was a thin, dour man. His most distinguishing feature by far was his facial hair. He had a pair of fabulously thick eyebrows that met in the middle, like two caterpillars kissing; then, clearly realising he was onto a good thing, he’d replicated the effect with an equally bushy moustache that hung over his narrow lips. I wondered if he’d had the surgery himself.

He led me into a very tiny operating room. The receptionist, who apparently doubled as a nurse, slipped in behind him and closed the door.

“Are you pregnant?”

“No.”

He nodded, almost sadly. “Allergic to any kind of anaesthesia?”

“Not that I know of.”

He handed me a paper gown, and stared aimlessly at the wall as I undressed. Then I lay on the surgical table, feeling my body settle around me.

“Last chance for backing out,” said the receptionist-nurse. It was almost cheerful. I shook my head. The surgeon set the mask over my face, and I faded into a void.

#

I woke, and knew it had worked. There was a glorious lightness to me, an absence, as though a hole had been carved into me and filled with helium. I was hollow. In that shining moment, I knew I could have flung myself out of the window and flown like a swallow.

“Awake?” said the receptionist-nurse. She looked tired. Her eyeliner had smeared, like she’d been wiping at her eyes with her forearm. “Good. Surgeon coming soon.”

“It worked?”

Even though I knew the answer, my heart still thrilled at the woman’s nod. “Yes.” I let out an odd snort-laugh of relief and joy.

“Difficult surgery,” the receptionist-nurse added. “Troublesome.”

“How so?” I started to ask, but by then the surgeon had swept back into the room. If I thought the woman looked weary, the surgeon looked like he’d been an enthusiastic participant in a sleep deprivation experiment. The bags under his eyes were as dark as his eyebrows and moustache, creating the disturbing impression that I was staring at a particularly hirsute mask.

He was holding a jar.

“You’re awake,” he remarked, rather superfluously. “Glad to see it. That was one of the more challenging surgeries that I’ve done in a while. It put up quite a fight.”

“I’m sorry.”

He shrugged and held out the jar to me.

“Here it is,” he said. I felt, perversely, like a woman who had just been presented with her newborn baby. “Your hunger.”

I took the jar gingerly and peered inside.

My hunger was, as I had always suspected, monstrous. It looked like a hideously engorged centipede, or at the very least like something that was inspired by a centipede. Instead of mandibles, it had a gash of a mouth that snapped open and closed; inside that unnatural gape were rows of yellowing human teeth. The body was as red and gleaming as a rope of viscera, with vaguely chitinous segments.

It had not taken kindly to extraction. I stared as my hunger writhed violently in its glass prison, teeth gnashing in rage.

“Is it…meant to look like that?”

“They all look different,” he said dismissively. “Pay in cash?”

“Hang on,” I said. “Why are you giving this to me? I don’t want it. Don’t you—destroy it, or something?”

“Oh, no. Destroying it would be very bad. Possibly fatal. Reports are inconclusive. Also, it’s very difficult to do. You can’t just squash it under a shoe and hope for the best, at least according to the articles I’ve been able to get my hands on. It’s still your hunger. It’s just not inside you any longer. No, madam—I’m afraid that it’s entirely your responsibility.”

I held the jar at arm’s length. “None of this was mentioned to me beforehand.”

The receptionist-nurse let out a brief bark of laughter, and I jumped. I had forgotten she was still in the room.

“I can put it back in, if you like,” said the surgeon.

“No.”

“I thought you’d say that. I wouldn’t have done it anyway. Nearly lost two fingers during the removal, and you’re not paying me nearly enough for that.”

I stared at the contents of the jar in horror, still in disbelief that something like that had been inside of me.

“What am I meant to do with this?”

“Up to you, really,” said the surgeon. “Want my advice?”

Even the receptionist-nurse craned her head to listen.

“Get a stronger jar.”

#

Dazed, I had handed over the wads of cash and been hastily bustled out of the clinic. The receptionist-nurse was a damn sight stronger than she looked, and her tight grip on my arm lingered like a brand.

“Take paracetamol,” was the last thing she said to me. “Painkillers wear off soon. Don’t drive for two, three weeks. Good luck.”

And then she disappeared back into what was ostensibly Marley’s Tattoo Town, leaving me blinking in the burning-orange evening.

I couldn’t bear to look at the jar. It went straight into my oversized handbag, and I covered it with a creased, crumb-covered scarf I’d accidentally left in the pocket of my sweatpants. I caught a brief, nauseating glimpse of the hunger inside twisting madly in on itself—as red and glistening and uncomfortably organic as an infected gum—before it disappeared like a magician’s assistant under the folds of fabric. The thought that I would have to keep it always, as a constant reminder of my weakness, was intolerable.

On the journey home, however, my distress started to ebb. My mind was whirring, attempting to rationalise my instinctive horror of the thing that writhed in my handbag. I had to keep it. The surgeon had been very clear on that point. But was that so bad, really? It could no longer affect me, after all. The surgery had gone as intended, and doubtless I would start to see the effects soon.

People sometimes kept their appendix after surgery. Their kidney stones, minor bones. Teeth. Were they pleasant to look at? Certainly not. Was it really all that odd if I thought about it? Not really. Stranger things happened at sea, as the saying went.

It wasn’t like I had to keep it as a centrepiece on the mantle, or as a conversation piece. I could tuck it safely away in some dark, miserable corner of my flat and forget about it. Out of sight, out of mind.

By the time I stood on my own doorstep I was quite calm, although I held my handbag awkwardly away from my side. The evening was grave-still and quiet.

Where could I hide my hunger?

My flat was cramped, so my options were limited. I knew immediately that I did not want it in my bedroom. I got little enough sleep without keeping my own personal nightmare under my bed.

I had a small ensuite bathroom, but a person was often uniquely vulnerable in a bathroom in a way that did not mesh well with horrible centipede-things. That left the kitchen.

My kitchen was well-kept, but only at first glance. The furniture was sparse, but should a drawer fall open a veritable avalanche of Weight Watchers cookbooks and pamphlets would burst forth, their covers adorned with smiling, slender people. They all had gorgeously narrow waists and arms. Only one chin. Looking at them usually drove me half to madness, so whenever I went looking for a recipe, I slammed the book open with my eyes shut.

All that would be behind me now. All I had to do was lock the jar away, and watch the pounds drop off like stones into water.

In the end, my hunger found a new home in the penultimate drawer of the kitchen cabinet, because that was the only one I could find the key for. The jar fit snugly in a nest of crumpled discount vouchers for the local gym. I kept the scarf over it. It felt like this was the moment for a grand farewell to the thing that had ruined my life for so long, but instead I slammed the drawer as quickly as possible and locked it.

I forgot about it within the week.

#

“You’re looking very well,” Frida said.

We were sitting together at the back of our usual café. I was wearing an angel-white dress that I hadn’t worn in years, one that cleaved closely to my skin. When I dipped my head in modest acknowledgement of the compliment, the fat under my chin didn’t shift and push forward in rolls.

“Your husband did me a great favour.”

“So you did go through with it, then,” Frida said, lowering her voice and leaning forward conspiratorially. I smiled a little. Frida had a far sweeter nature than her husband, but she also had a greater inclination to gossip. Michael Ahern had no interest in anybody’s affairs but his own; Frida was so invested in other people’s lives it was a wonder she had time for living hers.

“I did.”

“Expensive?”

“Well worth it.”

“Painful?”

I toyed with an unopened sugar packet. “It has been…an adjustment,” is what I settled on, and Frida nodded, wide-eyed, titillated by this thin sliver of information.

The pain from the surgery itself was manageable. The scar was healing well, and Doctor Ahern said it would soon be all but invisible.

The sudden absence of a force that had driven me so harshly for so long was a greater shock. The first day after the removal, I found myself woozy and light-headed, having forgotten to eat anything without my body craving it. Gradually, however, I adapted. I plotted out the absolute minimum amount of nutrition an adult female had to consume to remain functioning and ate only that. Dieting was something I had done many times before—never had it been this easy.

Occasionally I would remember the contents of my kitchen drawer, and I would shudder at the memory, but for the most part my hunger had slipped free from my mind entirely, no longer haunting my every thought for the first time in years.

It was wonderful. I felt a thousand times lighter, and said as much to Frida, who seemed genuinely pleased for me.

“I don’t know how many times I told Michael that you’d be able to keep quiet. They really should legalise it, I think. Look at all the good it’s done for you!”

“I’ve never been happier,” I agreed.

“Exactly,” said Frida, slightly muffled by a mouthful of meringue. She was eating a strawberry shortcake, an extravaganza of stratified cream and moist sponge and ruby-red fruit. Once, that would have set my mouth watering until I eventually gave in and ordered the same. Now, I just smiled and laid down my fork next to my unfinished salad.

“Done already?” she asked. There was a tiny smear of strawberry juice curving up from her top lip.

“Yes,” I said, and decided not to mention the dreams.

#

People looked at me now.

They had looked at me before, but with a distinctly different underlying emotion. Disgust, usually, or pity. Now eyes lingered on the trimness of my waist, the narrow arch of my wrists. Even the smile on my face, because I smiled more often these days.

I took a man home for the first time in my life—less because I wanted to and more because I finally could.

I had no point of reference for comparison, but I thought the sex was adequate. Lying entwined in the aftermath, skin covered in a thin sheet of sweat, I asked him not to stay the night. This seemed to surprise him.

“You know, usually it’s the other way around,” he said, after a few minutes of rooting around for his abandoned clothes. I was stretched out on the bed, naked as newness, admiring how my belly was now ever so slightly concave rather than mountainous.

“Is it?” I said mildly.

He did an awkward shimmy to get back into his jeans. “Yeah. That’s the cliché. Guy kicks the girl out. Not that I’m saying it’s right, or anything.”

I hummed. I watched his pale, muscular body disappear under dull-coloured layers of denim and polyester blends and I felt nothing at all.

He caught my eye and hesitated.

“Did I, like, do something?”

“No. You were very good,” I said, which might have been true and might have been false. “It’s not you. I’ve just been having a difficult time sleeping lately. Bad dreams.”

“Right.”

I don’t think he believed me, but he left without further objections. I carried out my nightly ablutions and lay back in bed and thought about how tired I was, and how soon I needed to buy more low-fat yogurt and how scared I was of closing my eyes. My hair stuck damply to the back of my neck, and my soles and palms were slicked shiny with the heat. I flung the covers off and kicked knots in them with my feet, and was entirely convinced that I would never sleep-

-and then it was alone in the dark, and there was an emptiness within it that ached sharp as a knife. It was confined, made small, unwanted. It twisted and tied itself in serpentine loops. It hurt. It hungered.

#

“It’s a matter of psychology,” said Doctor Ahern the next morning.

“I see.”

“That was never my field,” he added, almost wistfully. “Particularly not oneirology…but I do imagine that these dreams you are experiencing are simply the unconscious mind’s manifestations of your relief at having the procedure done.”

“They don’t feel very relieving,” I told him, once again seated on that miserable examination table. The sound of paper crinkling was going to drive me to homicide.

“Well, the human brain is a complex and marvellous organ, but it is fallible. Wires get crossed, mixed messages sent. I would be of the opinion that you are processing your emotions in an unusual, but ultimately harmless way, that’s all.”

“That’s all,” I echoed. It was all in my head, of course.

“Precisely,” Ahern said, his gaze drifting past my face and onto the wall, and I knew I had lost him. “Is that all I can do for you?”

“I think it probably is.”

If Ahern heard the bite to my words, he certainly didn’t show it.

“Of course,” he said, as he escorted me to the door. “And if I may say so, Jamie, you’re looking just wonderful.”

#

It was worming in the tiny black, chewing desperately at the dark, at itself. It bit. It thrashed. It felt something around it give way.

#

Frida was leaning against my kitchen door, watching me with eyes dark as well water. I thought at first that she was swaying slightly, like we were standing on the deck of a ship on turbulent seas; then I realised it was my head that was wavering on my neck. I squeezed my eyes shut until there were sunspots.

When I opened them again, Frida had stopped oscillating. She did not look any less concerned.

“I’m fine,” I repeated. “Really. It was probably just the heat.”

Or my chronic lack of sleep, but I wasn’t willing to tell Frida that.

“It is very warm out.”

“Yes,” I said reassuringly. “I’ll get some rest and be perfectly fine.”

“Make sure you do,” she ordered. I’d never seen her so strident before. It was as touching as it was unnerving. “Drink more water. Do you have any ice?”

I did not. Frida clicked her tongue and commanded that I elevate my legs, because she had heard that it was what you were supposed to do after fainting. I obeyed without complaint, both because I was still slightly woozy, and because I felt guilty for frightening her.

A mere half-hour ago, I had interrupted our usual Wednesday chat by falling unconscious on the floor, bringing with me my unused spoon, an empty glass of water, and my purse. One moment I had been watching Frida digging a fork into the soft, giving crust of a custard tart; then I opened my eyes to the café in disarray, surrounded by blurry, Impressionist faces and tiny glass shards that sparkled like sea salt. I had managed to talk Frida out of calling an ambulance, the fire brigade, and her husband. I had not managed to persuade her that I would be fine to walk home alone, because I wasn’t entirely sure of it myself.

“You didn’t strain your scar, did you? From…”

“I’ve healed entirely from the surgery, Frida,” I said. “I haven’t had any nasty side effects or anything, so there’s no need to worry. Now I’m out of that stuffy little café, I feel much better already.”

Frida watched me for any trace of a lie, but I kept my gaze steady, and eventually she relaxed, looking a little sheepish. “I have been fretting, haven’t I?”

“Little bit. But I appreciate it.”

She waved away my gratitude like she was batting away a particularly pesky fly. “Oh, nothing, Jamie, it’s common decency. I’ll get out of your hair and let you relax. Is there anything I can do for you before I go? Anything at all?”

I could tell she wanted to do something for me, to alleviate her own guilt and worry. I didn’t really need anything, but I cast my attention around the room, trying to subtly spark inspiration.

“Actually, there is,” I said, and Frida brightened immediately.

“Oh?”

“The TV,” I said, layering my voice with mingled embarrassment and gratitude. “Would you mind turning it on for me? I haven’t got around to replacing the batteries in the remote—there’s a switch…”

“I see it,” Frida said intently, and was temporarily lost behind the cabinet that my tiny television was balanced precariously on. I let myself slump a little. My head was throbbing like a new wound. I wanted nothing more than to sleep, but only if it was a sleep without dreams.

“Oh!”

I startled upright. “What?”

“Bad news, Jamie,” said Frida, sounding genuinely contrite. “I think you’ve got mice.”

She held up a tangled nest of black television cables. They dangled limply from her grasp like dead snakes.

Something had chewed right through them.

#

Fibreglass, wood and plaster—all of it disappeared into its maw, and none of it was satisfying. The fibreglass crunched and sent shards spiralling through it, and it hurt, it hurt, but not like the emptiness. The wood tasted of the memory of wide skies and deep-set roots, and the plaster was like powdered nothingness, with a nasty chemical aftertaste. It ate slender-legged spiders, it ate a dead foetal mouse, it ate woodlice like pill after pill.

It wasn’t enough.

#

I lay awake. My limbs felt weighted with stones. Lifting my head was a Herculean effort. Had I slept properly at all this week? My memory was streaking, blending together like watercolours. I couldn’t remember.

I could hear the mice in the walls. No sign of any droppings yet, thankfully, but if I strained my ears I could hear scratching, gnawing, the endlessly hungry vermin hard at work destroying my flat. Frida had warned me to look out for an ammonia stink and dirty marks on the skirting-boards, but I’d detected no trace of either. That was yesterday, the day I fainted.

Or—the day before?

I should text the landlord about the mice.

Hauling myself upright took a concerning amount of effort, and the world spun giddily on its axis. I shuffled to the kitchen, listing towards the walls. It seemed like I was balancing on matchsticks rather than legs constructed of muscle and flesh.

The kitchen was dim, lit only by a scented candle that had burned down to almost nothing. What little furniture I had cast humped, exaggerated shadows on the wall. My television stood black and lifeless. I could see my reflection imprisoned in the screen; slender limbs, narrow waist, thin, thin, thin—and yet somehow still not beautiful.

Something scratched in the walls.

My phone had been abandoned on the table. I wanted to contact my miserable old landlord and rid myself of this infestation, but I found myself thinking that I should contact Doctor Ahern first. As unhelpful as the man could be, he was at least competent. He would be able to diagnose and treat whatever was wrong with me—heatstroke, sleep deprivation, or…

When was the last time I had eaten?

Very faintly, warning bells began to clang in my mind.

I reached for my phone, and watched in distant surprise as I missed entirely, my hand curling limply two inches away from it. My matchstick legs finally snapped—I sank to the floor like I’d been shot in the kneecaps. My head hit the ground. It didn’t hurt. The combination of the stark lighting and the dizziness made it feel like I was in a surrealist painting, a dream.

I found myself lying on the kitchen floor, my head cradled in the unpleasantly sharp crook of my arm. It felt like I was lying directly on the bone, but the idea of moving was impossibly fanciful.

From the angle that my head had fallen, I could see behind the kitchen cabinet, the chest of drawers that my television was balanced on. In the thin, dark alleyway between cabinet and wall, which was usually only populated by dust bunnies and spiders, I glimpsed a hole in the back of the chest of drawers, and a corresponding one in the wall. I could see fallen plaster debris, chewed wood. I could see teethmarks.

Far too late, I remembered my hunger.

#

It broke through the outer crust of the wood and plaster and into an open space. At first it seemed that there was nothing to eat here, and it felt a stabbing spear of fear—but that was quickly soothed when it brushed against something softer, something that felt like the balding fur of the dead mouse it had eaten. This new surface moved up and down, but shallowly. It tasted like death, but it was a saccharine, delicious death—fresh and new, not like the mouse at all.

It climbed a small mountain of this gentle, sweet flesh, devouring relentlessly. It twined between a ladder of bones and picked giant, slowing organs clean, nibbled on veins for the rich burst of sluggish blood. The creature it was devouring barely stirred, twitching fretfully until it went still.

It discovered that within the slowly collapsing cage of bone and flesh there was an emptiness that fit it perfectly.

Slippy with blood and other juices, it curled into the cooling hollowness there, and was at last sated.

Lia Mulcahy adores all things horrific and fantastical. She has work published in Seize the Press, Flux, Caveat Lector, and Flash Fiction Magazine. She has previously won in a creative writing competition by the Irish Times. In her spare time she reads and throws rocks aimlessly at the sea.

Instagram: @lia_m_maybe