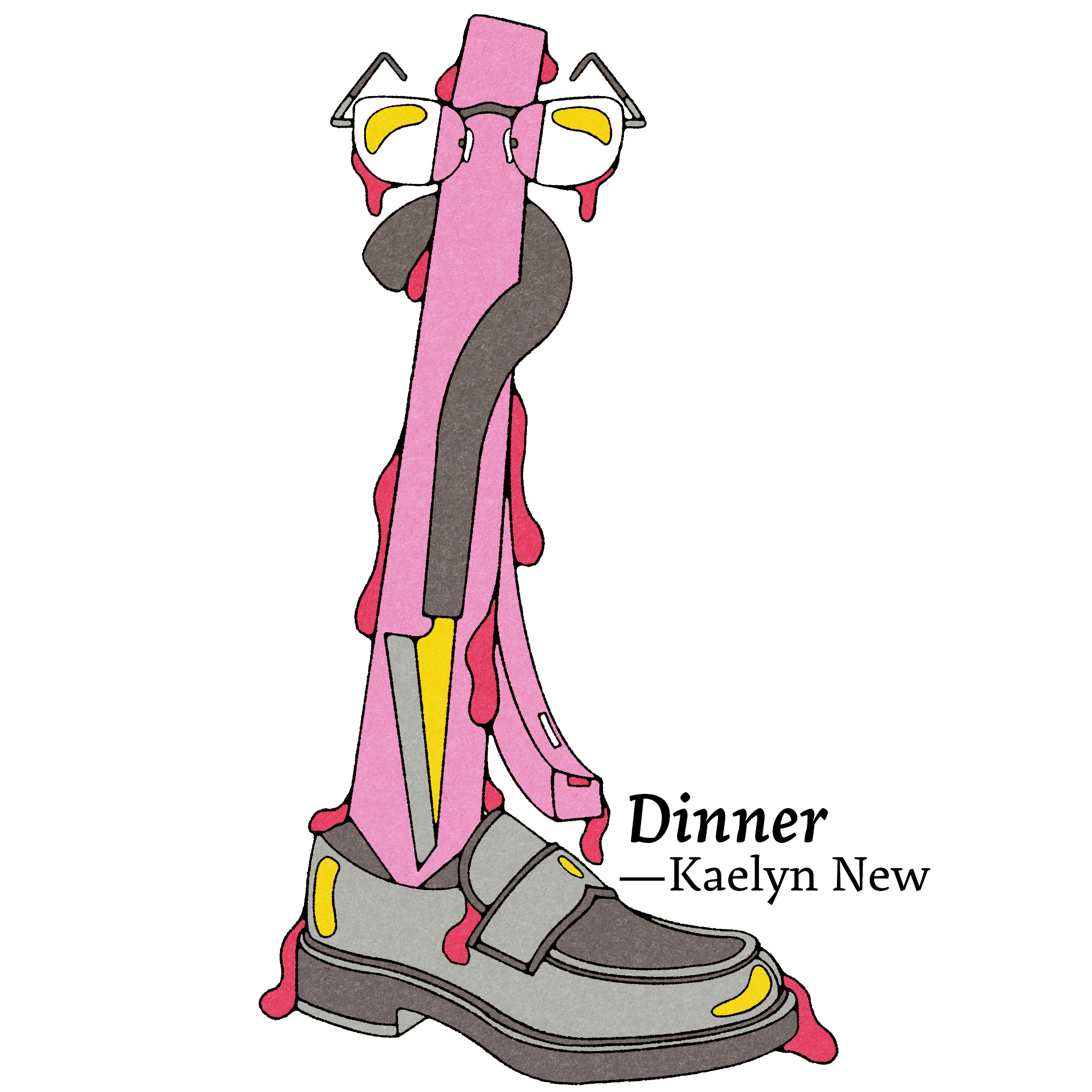

Dinner

Pink juices drip, flowing and oozing—freely, deliciously—down my cheeks, lips, face. And I devour. And it’s delectable. Can you blame me?

It’s almost a date, I think to myself as I take another bite of the meat, an erotic bite—the self-indulgent kind where He writes zeros on the check after you feast, smacking your ass as you step into the valeted BMW to go back to His place. And I really tried, too. With everything. I cleaned the kitchen and placed the slabs, bathing in butter, in the oven. I marinated each piece in a red wine vinaigrette sauce boiled to a perfect syrup. Good cooking requires patience. Lots of it. Each ration is perfectly calculated, adorned with rosemary and thyme.

There is bread and there is wine. The finest merlot, one that He had selected from a vineyard in Italy during some work excursion. The meal barks at me, here, take and eat this. This is my body. Drink from it. This is my blood. Blind adoration will only take you so far before dropping you from that treacherous edge. I am greedy, then. So be it. I signed the papers like He asked. They are here right now, a napkin for my gluttony. I lick the empty space around my mouth. It really is delicious.

…

It was a sticky summer day when I first saw my mother hold the honesuki in her grip, instructing me along the way. I sucked salty tears into my mouth—the childish, inconsolable sort of meltdown in which air forgets to seep into the lungs and a throbbing ache infiltrates the brain, the kind of meltdown I would only have once in my adult life. I watched as she grabbed Sunny from the coop in the yard, hoisting her by her long neck, feathers flapping in distress. With two swift movements across the neck, it was over. A thick red trickled down my mother’s hands.

“You can’t name them, sweetpea,” she said, wiping the blood from her arms with a rag. “You get too attached.” And we ate Sunny for dinner. It was never barbaric as much as it was sad, but with repetition, all small tragedies become normal.

My parents were blue-collar, real salt of the earth people—homesteaders—stuck, perhaps, in another century. My father was a carpenter by day and a drinker by night. My mother tended to the saccharine fruits of the season sprouting in the yard, the animals roughing in sheds and pens, and her daughter—myself. She was tender with affection, but entirely raw in disposition, with muscles bulging and permanently stern expression, and my father was nothing if not wholly in love with her in every way that a man could be. He rubbed her thick shoulders the moment he walked in the door each night; he slept with a mere foot of room on the mattress, bottles on the bedside; he left notes with scribbled hearts, sloppy from booze still in his blood, on the kitchen counter for her to find in the morning.

“The happiest accident,” my mother would say, stroking the strawberry strands of my hair, my head resting in her lap. There was no resentment toward me in that small, bustling house—no slammed doors nor clenched fists. There was only love, enough of it to heat the house amid the most biting winters. But before my untimely emergence, I knew my mother dreamt of an undemanding life. One where money wasn’t tight, and bills were paid. One where she could rest in my father’s arms eternally undisturbed. She can now.

I traded burlap dresses and my mother’s hand-me-downs for something faster after their deaths, resolving to be around other people as much as possible, as if to remind myself that I wasn’t just a figment of my own imagination. I forced interactions and submitted job applications. I never applied to college. I never finished my senior year of high school, really. But tragedy doesn’t wait. It doesn’t anticipate a reprieve in a busy schedule, an important life event. It couldn’t have known my plans.

…

He was charismatic. That is as much as I know about our first interaction, His fingers fumbling through His dark hair that was speckled with pepper flakes of gray, His thumb moving to push His wire-frame glasses further on His nose. Large hands. Good with them? Intelligent. I could spot it at first sight. Rich. I could tell because He was buying from me. When I fitted Him for the tuxedo—black with miniscule gray pinstripes to match His mane—He looked down at me, dark eyes gloating, and I felt blood swim in my cheeks. $750 dollars for one tuxedo, and He paid without looking at the price, only sliding His business card over the counter when the transaction was complete. A grand romantic gesture.

And I wasn’t looking for love, to be entirely blunt, but I was hungry for companionship. I awoke restless in the nights in those days with a midnight craving for coyotes howling in the yard, my father stumbling his way to bed. I was greeted by whirring sirens and honking cars, streetlights that never turned off, the beams stretching their fingers through my closed curtains. I didn’t want love as much as I desired stability—savory air wafting into my bedroom, the television buzzing down the hall. But love found me and lured me from my hiding. That was my own fault, I admit.

…

For beginners, the easiest way to kill a chicken is to use a chopping block. It’s not the cleanest method, by far, but young feeble hands are incapable of maneuvering the chicken with one hand and slicing with the other. I was seven when my mother held down the nameless hen, extending her small neck across the wooden block. I closed my eyes and swung, hitting her right above the shoulders. Clean through. I watched her legs perform a twitchy dance as my mother chucked the head in a bucket. “Next time, be sure to watch,” my mother said as she plucked the feathers. “We don’t want no missing fingers, sweetpea.” I nodded. She told me to wash up; dinner would be ready soon.

Love is awfully peculiar, I have found. It’s sadistic, trusting someone enough to reveal their bare neck, head on a chopping block, praying they won’t swing. If they do, it must be for the better, right? Love requires trust. Love requires sincerity. We move past our own differences; we try again with the little things. And love just happens. I don’t know why. It just does—it just did.

…

Charming persistence. We went on our first date after He visited me at work twice more, and each time, in a grandiose show of Himself, He would buy things in excess that He didn’t need: slacks, ties, shoes, socks. And He would lean His bulking frame over the counter as I tried to help other customers, licking His lips and rolling His eyes playfully. When He asked me what I was up to one Sunday during His third visit, I couldn’t lie. Nothing.

“So, dinner tonight?” Yes. Dinner tonight.

“They don’t have Michelin Star restaurants here in Boston, so you’ll have to pick something else,” He smirked.

Once we arrived, He ordered a steak with wine. “Extra rare,” He cautioned the waitress. “Very pink.” When the waitress brought His meal, he devoured, the juice dribbling out of His mouth and into his lap. I learned that He was a shareholder for Silk & Bowin, one of the “most prominent and upcoming companies on the East Coast.” I joked that He must make so much money and he motioned with His arms, beckoning me to look around. Hours later, sloppy with drink in His apartment, He caressed my face as I stuttered. He could’ve killed me if He only wanted, if He were one of those sick perverts on the news every other night. Instead, his thumb fell and rested on my chin, and He kissed me—just a peck—before carrying me to bed with Him. Lust and hunger are often indistinguishable. He was hungry then, in those dark sheets, but I was too. And can you blame me?

It wasn’t a one-night stand. He wasn’t the boy in high school who enthusiastically ripped the cloth from between my legs in the backseat of His car, kissing my lips in mutual pleasure before refusing to speak to me in the hallway. He was beyond that. Mature with age, I had assumed.

There were gifts, of course, because love is often transactional. He would buy me a date-night dress and I would let Him peel it from my body. Transaction complete. Three weeks after casual Sunday-night dates, He introduced me to His business partner who offered me a job in sales at a sister company. It was a salary-pay position with full benefits. I would’ve been an idiot to refuse, as if sewing stitches and toting tape measures would sustain me forever. The office, located in the heart of downtown Boston, was only a five-minute ride on the Subway from my closet of an apartment. I had to learn PowerPoint, read graphs and excel sheets, and spend most of my time on the phone. This was grown-up. This was beyond me, my twenties, my naïveté. It was so much more.

He picked me up from work in a black BMW with polished leather seats and took me to dinner, sticking His fingers in my mouth on the drive. We talked about things that didn’t matter and laughed at jokes that weren’t funny. He kissed me on the forehead and held me across the chest as I slept. After four months of resting opposite Him, I asked if He was seeing other people and He scoffed before refuting the notion profusely. I told Him that He was allowed to see other people since we weren’t official, and He promptly asked to make it official. After our fifth date, giddy with wine, He joked that he would marry me and asked to speak with my father. I slurred out the story and watched a real sadness fill His eyes.

…

Cancer doesn’t ask permission to kill; it simply does. Most people are undeserving of a sickly demise, and my sweet mother was no exception. But I was too enamored with the buzz of public high school, libido-fueled crushes, and recreational drugs to notice the color vanish from her cheeks. She sat me down outside as Autumn descended, in full view of the ripened peach trees, the fading sunlight caressing each branch. Her cracking words were only silenced by an inordinate ringing in my ears. Lung cancer. Inoperable. Prognosis. Weeks to months.

The fruit fell to the ground that season with no one to pick it up. Each piece rotted in our yard, my mother likewise in her own bed. I watched as her muscle fell clean from the bone and her breath hardened into a rattle. My father put aside the bottle to be fully present, cautiously anticipating her last moments and beckoning God for more time. He slept on the cold, wooden floor as winter approached to give her more space to find comfort in the bed, his hand upright and outstretched, clinging on to hers. He left notes on her bedside table that she would never read and rushed her to doctors’ appointments as if miracles were really possible.

It wasn’t shocking when the coroner had to come wrap her body in a white sheet once the snow started sticking; she had overstayed time’s welcome. She beat the odds by months, but at what cost? I hadn’t heard her sing-song voice in the kitchen nor blade on the chopping block since she was diagnosed. She died long before her pulse stopped, and I was forced to watch it from the doorway etched with various heights and dates. So, no, I wasn’t shocked when she died, nor was I surprised when my father swiped the rifle from the shed one spring night, the same one my mother had held to her bosom to butcher the cow just years prior. He pointed it beneath his chin in the darkness and fired, sending crows lurching from the top of the house and the chickens into an alarmed frenzy in their coop.

…

I didn’t want a wedding; there was no one I could invite. He said he understood what I meant, and we eloped in Europe. The trip spanned seven countries and countless taste buds, none of it on my dime. “You’ll find the wine is best in the valleys of France,” He told me before we departed, and He was right. The dark flavors of Syrah from Rhône, the Loire Valley’s honeyed Chenin blanc—it was ambrosial. In northern Holland, we rented electric bikes and sped across the coast, inhaling breeze saturated with cow shit as the ocean sprinkled our faces. As we perused, I caught glimpses of animals grazing—cows, chickens, goats. I felt a pang of nostalgia, only for a second. A life that I had forgotten, skills I no longer used.

When I returned to work, still in sales, the girls squealed at their desks and asked to see the ring. I gushed, as one does when they are freshly married. They answered me with a choir of ooohs and ahhs. They were not my friends—we guzzled drinks after work without really knowing anything about one another. They were acquaintances that pretended to care, and back then, that was enough.

In high school, after my parents died and I sold the plot of land, I returned to school for two days mid-spring semester. Everyone stared at me, but not a single person knew what to say. Sure, the silence was better than being hounded with questions and embellished condolences, but everywhere was silent—the school, the bitter, small house, the broken coops and pens in the yard where animals used to live and die. Even the wind seemed to stop its ripple through the flowering buds on tree branches, molding fruit still on the mulch below.

I told the girls at the office nearly everything. I told them about the prenup that His mother forced my hand on paper to sign. What a bitch! they had scoffed in near unison. I told them about the new house—a Victorian-style cottage outside of the city. I told them about the sweet romantic getaways. I would tell them when He left flowers on the counter in the morning before work, and I would explain, in detail, the arrangement of the bouquet. I would never tell them later, though, about the week-long business trips, my paranoia that seeped in like a blood stain, the closed fists and slammed doors. No, they had to confront me with hushed whispers. Even then, I lied.

…

He wanted a baby, so I gave Him one after much deliberation, resting assured that my birth never wedged my own parents apart. I labored for twenty hours under hot fluorescent lights while tightly gripping His hand, and His gaze did not waver, His mother’s likewise from the corner of the delivery room. He stroked the beaded sweat on my forehead as I screamed and cried and groaned. And when I was too tired to scream, cry, and groan, He reassured me with soft, pillowy words. We want this. You are doing so good. You are almost there. When I felt my baby come out of me, I was overcome with relief, as he took a breath and wailed, followed by a sudden shaking cold. I watched as He yelled at the doctor and the nurses standing nearby, commanding them to do something. I watched, like a passenger in the back seat, as I was wheeled out of the room, deserting His muffled cries. I saw white lights fly systematically overhead, just for a moment, before I welcomed the darkness.

I couldn’t decipher the words coming from the doctor’s mouth when I came to, garbled as though my head were forced underwater. I had, what I know now, to be a postpartum hemorrhage. When I delivered the placenta, blood gushed out of me, as though my own anatomy was an open wound. I knew that I almost died. I knew that cold feeling to be death. I could see it on my mother’s face when her time came. There is light and then there is nothing, and I was so close, deliciously close, to that little oblivion. Once I was walking, albeit crouched, as I shuffled about the maternity ward, He told me that He had a name idea for my boy. His mother held my shoulders in the bed and braided my strawberry hair, noting that she liked the idea “very much!” The boy would be named after Him, my loving and devoted husband, just as He was named after His father and His father’s father. I laid my father’s name on the table and watched His brows sew together. His mother pursed her lips. “Well, that could be his middle name,” she smiled from the corner of the room, timid, as though I would bite. Exhausted from the effort of pushing life through my legs and pumped to the brim with drugs, I tentatively agreed. I would call my boy Junior, Junie for short.

When Junie cried in the night, He would rush from my side of the bed to console him, rocking Junie methodically back and forth. He would cease his wailing, secure in His arms. In the day, He would leave for work, and I, still on maternity leave, would hold Junie to my breast and rock back and forth, the pain still tearing my body in half, my womb protruding. When he screeched, I would hold him to my chest to no avail. The cries echoed down the empty hallways and out the open windows.

When I returned to work, He paid for a nanny, a much younger girl, freshly nineteen, to soothe Junie’s cries in the day. I had asked Him after the birth if I could quit my job. Surely, He had enough money to support us both, but He was firm in His disapproval. “The kids will be in college someday,” He had said. “There are so many things in the future that will cost us.” He was right, in more ways than one, and that prenup ensured that I needed money of my own. Just in case. Just in case.

…

When you kill an animal, it is important to be precise in all respects. There is little room for learning when you may cause the proliferation of suffering, I have found. When I tried to kill my first bull at thirteen, I watched as my mother demonstrated with a target placed on a tree. She had haphazardly drawn a bull’s face on a sheet of paper, with uneven horns and blackened eyes. She held the rifle on her breast, her left arm extended to support the forestock and her other arm supporting its base, finger on the trigger. I inspected her form as she fired, and her body received the kick without wavering.

When my turn came, I was close to the bull huffing in front of me. I could see life in its eyes—a life that I had watched grow and change from the day we brought him home to the pasture. I shuffled my footing and aimed, creating an imaginary target at the intersection drawn from the tip of the horns to the opposite eyes. I closed my eyes and pulled the trigger. The rifle’s kick sent me two feet back, and in the aftermath, I plugged my ears. I didn’t drown the noise to prevent hearing the bullet, but instead, the yelps that the bullet left in its wake. I had shot through the poor thing’s muzzle, the bullet gliding straight through its throat. It screamed as it tried to inhale through blasted tubes that could no longer carry oxygen. I covered my eyes, and my mother sprang into action, loading the rifle and firing it directly into its forehead.

“You must always look!”

“I am sorry,” I cried.

“Keep your eyes open.”

We bled the animal over my stifled sobs. I wasn’t distressed that I had disappointed my mother; she knew I was learning and understood. I sobbed because I knew that the poor thing’s cries would haunt my dreams in the weeks that followed. I sobbed because that bull did nothing to warrant a painful death. The animal’s meat, sliced and frozen, lasted us practically a year, and with each bite, I could hear it all over again.

…

Junie was enrolled in daycare once he was old enough to stumble like a fresh-born foal. I would pick him up on my way home from work and cook meals for when He walked in the door. Like clockwork, He would step in, take His coat off and say, “Something smells good.” As I stirred spices and butter on the stovetop, He would wrap His arms around me from behind. I would cradle my head in the nape of His neck and sway. Love was there then. Love was there in the mornings, when I would dress Junie for school, and He would prepare cereal and coffee in the kitchen. It was there when He held me in His sturdy arms each night, a fortress of a life that I had built for myself.

But He wanted another child, and He was insistent. And I was weary, rightly so, but I tried. We tried. Nothing. There weren’t parallel lines on the dollar-store tests, nor plus signs on the more expensive ones. Barren, the doctor had told me after I went for a routine check—in different words, of course. Barren. Nothing. Empty. I couldn’t even do IVF, the doctor explained as I tried to steady my breath, because it would require a functioning womb and mine was nothing but dysfunctional. Broken. The hemorrhage—that gush of bright red on the sterile table, my feet still in stirrups—had ruptured my uterus beyond even surgical repair. When I called Him while he was still at work, He answered with eagerness. “And?” I told Him. Silence. A sigh, perhaps a hand fell over His mouth, or He rubbed his temples with dissatisfaction. More silence—a conversation as vacant as my insides.

“It’s okay,” He said softly. “We will talk about this once I am home.” But we didn’t, really. We never brought it up then. It was only later, and by then He quietly blamed me.

I think, at some point, I became someone He hated, but it is hard to pinpoint the moment with exactness. He, too preoccupied with work to remember the love, and I, too preoccupied with my own obsessions to care for the house, for Junie. He had gotten a promotion right after Junie turned two, right after his fourteenth tooth emerged from the gum. Of course, this meant longer hours, but it also meant business trips and time away to the west coast. There were no more cereal boxes on the counter in the morning nor roasted coffee in the pot. I would put Junie to bed each night and mourn the empty space in the bed. I would turn on the TV to hear conversations as I drifted to sleep, and I would pull His dirty shirts from the hamper to inhale the scent. I would rush to work late in the mornings after dropping off Junie, and I would silently resent myself for not being there enough for him. I knew he was growing and learning; he would come home with me in the evening, breathing new words to life in his vocabulary.

When He would return from week-long excursions, He would swing Junie by his hands in a circle, twirling him to His favorite songs on vinyl. We would drink wine and talk about our weeks. I would tell him new things about Junie; he learned how to say “funny” and had been using it out of place to describe everything. The sky funny. I am funny. He would laugh, a boisterous chuckle straight from the chest, and I would move to tell Him about my life, how Janice from work broke up with her dirtbag boyfriend, how sales were down, how traffic on the interstate has been bad. But it was all so mundane. All of it. He grew eerily quiet on the nights that He was home. I would ask about work, and He would fill the space with one-word responses. I would ask if he was okay, and He would say that He absolutely was. But silence also breeds delusion. At least that is what He told me when He awoke to me snooping through text messages in His sleep. There was nothing, of course.

There is very little in this world that is meant to last, and it is the finiteness that makes it beautiful and frightening. Marriages fall apart every day. People fall out of love and break vows and raise their voice in anger.

…

My father had only raised his voice toward my mother on one occasion that I can recollect. He raised his voice and demanded that she stay, demanded that she not leave him there, explained that he didn’t know what to do. She would not listen, as she lay lifeless in white sheets. My father screamed at the corpse. If rage could have brought her back, she would surely be here now.

But He raised His voice at me after returning from a trip. I was preoccupied with work, sitting on my laptop in the living room, tracking percentages and tally marks. Junie was crawling on the floor in front of me, a twinkle in his eye. Time passed. More spreadsheets. More focus. I heard, through that focus, a breathless cough and turned to see Junie glaucous on the floor. I cried out and picked him up, knocking him hard on the back, and He rushed down the stairs and to my side, grabbing Junie’s body and dislodging the button from his throat. Junie had choked on the button of a teddy bear, one that I had gotten him just weeks ago.

“What the fuck is wrong with you?” He turned to me after Junie began wailing, inhaling, and exhaling. His arms were raised then, and I watched as His left fist clenched toward the sky. Was he about to hit me? Perhaps. But He stepped away, resolving to breathe aggressively, rhythmically.

“What?”

“Are you not watching him?”

“I was,” I huffed. “I just—I had work stuff to do.”

“You have to watch him,” he commanded me, only later admonishing me for being stupid enough to purchase a teddy bear with buttons on it for such a young child. Children love to chew, after all. It was my fault. I agree.

Weeks passed in which He stayed home. I would arrive home from work, pay the nanny, change Junie and feed him before heading to bed. He would lay stiff in the bed that I had made in the morning, turning His back to me in His sleep. He didn’t touch me anymore; His fingers refused to wander up my skirt or into my mouth. It was empty, but He was there. But in the following months, He grew even more distant and hollow. When I would see Him physically, I wanted to reach inside of Him and pull out the love I thought he had hidden. He would play with my boy, taking Junie to sprawling fields and passing a ball, but He would not entertain the idea of me. Naturally, I began reading through emails and text messages, snooping through bank statements. Nothing. When I confronted Him about my suspicions, He laughed in shock. What are you talking about? You sound insane right now. Why would you say that? But the girls at work began to whisper. His secretary. California. Lingerie. The bar. Shared hotel room.

…

I asked Him to have sex with me when He returned home one weekend. I figured if He could feel me, He could remember the love. He refused. “Too tired,” He said, and a resentment grew inside me like a child. I crept out of the bed and into the bathroom and vomited in the toilet. When was the last time He touched me? I couldn’t recall. It was shortly after Junie’s birth, I figured, when the pain still ripped down my abdomen. And He enjoyed it. He must have. We were happy then. A clenched fist again. But it is not His, this time. It is my own.

I stared into the mirror for prolonged periods in the morning and before bed, so long that my face grew lengthy and distorted. I looked at the bulge of my stomach with disgust, the pink stripes around my midsection with contempt. I fed Junie at night and forgot to make dinner for Him when He arrived home. He complained. I set the table for one and began sautéing a pan.

More time passed. We attended formals for His work with Junie, and He would introduce the boy as His, as though he were not straddling my hip, arms around my neck. When I refused to eat, He told me, for the first time in a year, that I looked “really nice.” I starved and hoped He would drunkenly pry my legs apart. There was no love there, not anymore, not from Him.

When I asked Him in bed why He refused to touch me, He said He didn’t know what I was talking about. And when I tried to push further, He told me to go to sleep.

“But are you not attracted to me anymore?” I protested. He rolled his eyes.

“What?”

“Am I still pretty to you?” He sighed and yawned. “Or is it because we can’t have another kid? Is there someone else? What is it?” And I was begging at this point, begging to be touched if I could not beg to be loved.

“We aren’t talking about this right now.” So, we didn’t. And we never did again.

…

When He presented me with divorce papers, I refused. “If not for me, stay for Junie,” I argued. “He needs his father.” But He would not. Instead, He would steal the fruits of my labor every other week. One week away to fuck a secretary half His age, another week to pamper the child that I had forced from my body. This was the decision, and it was final, He had said. I taught Junie to sound each consonant. I was there for each first step, first word. He was not. I refused this proposition. I laid in the bed with Him motionless and felt a chasm of bitterness in those pale sheets.

When you stare at a portrait for too long, you notice small imperfections. When you stare for longer, the imperfections multiply until the entire picture is hellish. While I designed to fix these imperfections, the meat began to fall off the bone. I became frail like my mother in her bed. Even then, even when I looked “really nice,” He did not want me. Perhaps she was younger, this secretary. Perhaps she fucked Him with an absence of love. Perhaps she remembered to cook dinner without the hum of a child in her ear. There is only perhaps.

…

When someone you love dies, you forget a lot of things. I have forgotten the little conversations shared with my mother at the kitchen table, the precise way she used to style her hair with empty soup cans. But I have not forgotten her voice. It wafted, syrupy like silk and intensely deep, through the chilled morning air as I slept. I have not forgotten much of what that voice taught me as a child.

Meat must immediately be placed on ice if not consumed. When frozen, thaw under cool water to prevent the flourishing of bacteria. To ensure the finest quality of filet, the animal must starve for twenty-four hours prior to its execution. I did not set the table last night. When He arrived home, I told Him to microwave some meals from the fridge. He protested. “There’s nothing in here.”

“I must’ve forgotten to go shopping.”

“Jesus fucking Christ.”

“What?”

“Are you doing this to me because of the papers?”

“No,” I replied. “Just forgot.” And in all truth, I had.

When slaughtering, it is important not to startle or excite the animal as this can cause excess bleeding. When He arrived home from work today, He took Junie to play in the park, returning before dinner. I fed my boy.

“Your mother called,” I told him. “She was just checking in. Said she misses Junie-bug.”

“Oh.”

“I was thinking he could stay at hers tonight,” I told him. “We should discuss this.” The papers were clamped in my closed hand—a fist. He agreed and I dropped Junie off, bags packed, at his grandmother’s house.

Of course, a rifle is the most humane way to kill a large animal, as to prevent any excessive human suffering. But I was not humane. I do not feel humane still. No, I am an animal, and I am wholly famished. I pulled the honesuki out from its drawer and set it on the counter.

“What are you making tonight?” He asked me. I did not answer.

It is important that the animal is slaughtered in a sterile environment to prevent contamination. I wiped cereal flakes from the counter and mopped the floors. We sat at the countertop. I brought the papers with me, a glimmering white marked with legal jargon. I tucked the knife in my sleeve without him noticing. When slaughtering an animal with a knife, make two parallel cuts along the jugular. He began to speak of some lawyer, and I pushed the papers aside.

“I miss everything,” I told Him. A silence so succinct and familiar. “Can I hold you one last time?” His eyes shifted as He hesitated.

“Sure.”

And we touched. Just once. I walked behind Him and cradled Him, just as He did to me in years prior as I would prepare dinner. I pulled the knife from my sleeve inadvertently, and just like my mother instructed me, made two vertical slits on that bare, exposed neck. I kept my eyes open and watched as He bled on the floor. After slaughter, it is necessary to bleed the animal by cutting from the breastbone to the rear on the anterior side. I slid the knife down vertically, cutting His pressed white button-up in the process, before sectioning the meat and removing bones.

Now I bathe in His infidelity, licking my chops like a starving cat. I suckle on the juices of the sweet little things, the innocent lies told here and there. I will be gone for two weeks. The company needs me. I love you so much. I would do anything for you, you know that. I scarf down promises broken and pieces of me stolen. I indulge in delectable paranoia. I devour responsibilities I was punished for forgetting. What the fuck is wrong with you? Are you insane?

And it really is delicious.

Kaelyn New is a writer and editor from Denver, Colorado. She recently graduated from Gonzaga University with a dual major in English Writing and Political Science as well as a minor in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. When she isn’t working, she is likely spending time with her adopted black cat, Salem, that crossed her path over two years ago.