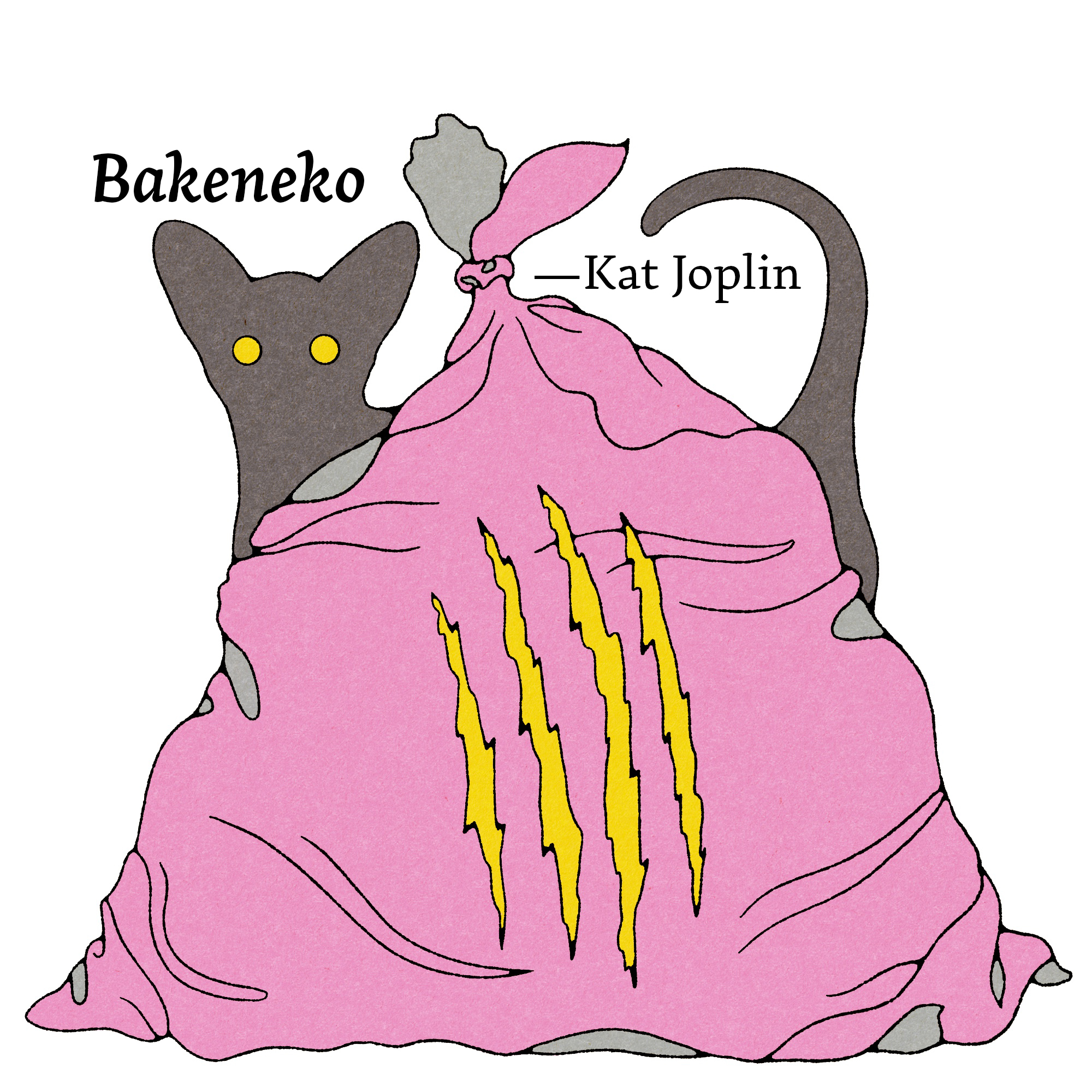

Bakeneko

Have you ever heard an animal talk?

I’m very uncomfortable around animals. I think maybe it’s because I didn’t grow up around them—my parents were both quite allergic, and my grandparents lived in a high rise. I’ve never had a bad experience with animals, and I’m not super afraid per se. But there’s something that makes me uneasy when I’m around them for too long.

I remember quite some years ago I had the perfect experience to explain my feelings. I was at Umi Tamago, the mid-size aquarium park on the coast. The jellies were pulsing in their dark, suspended globes of water, behind thick panes of glass. Jellyfish were always on the near end of acceptable to me, because they barely seem like animals. Rather, they were like oil pools in water, jumping and stretching the way oil and water do when you shake a pan.

Next, my friends walked me to the mammals section, and that’s where the discomfort began. I saw a massive, magnifying wall of glass stretching down the corridor, and behind it a pale gray tank. As we approached the glass, a dolphin floated down to us and hovered there. It was fascinating—I can’t deny animals fascinate me—but it was the eye that made me shudder. Its eye, flat and dark in the water, stared through the glass at me in a way that was much too intelligent, much too aware. It was an eye that was trying to speak to me.

Other people like that, I think—the alien mind trying to come closer. But for me, it sends shivers down my spine. I don’t like animals that come too close to being humans—dolphins, parrots, apes. Some people like when that line is blurred, and for others like me there’s a natural revulsion.

* * *

The first time I was genuinely scared by an animal, it was not what you’d expect.

I was walking through one of the large parks that dot the city to which I’d moved. It’s not the most beautiful city in the world, with its dull, tile-paneled beige buildings and broad grid-like streets, but there’s a charm to the old folks who populate it and the cab drivers who chat about your day. This park is a big one, with thick undergrowth and towering trees and little wooded slopes. In the summertime, bugs and songbirds make it chatter like a jungle, but in the cool fall it is mostly still.

I wandered alone along the footpath until I was surrounded by foliage, something I might be nervous to do as a woman if I lived in a major city. There were some large crows cackling overhead and springing from tree top to tree top, scolding me with their long hooked beaks.

I entered a clearing and a cluster of crows swept up from the ground on the far side; nothing unusual. But as I was passing, I heard something that made the hair on my neck stand right on end.

A voice said, “Hey, you.”

And the most arresting thing was, the voice sounded just like the crows quietly chattering above: a deep, dry croak.

I froze and my hand went to my cell phone. A part of me wanted to rush on, but I was in the clearing now and the path ahead was much thicker underbrush. Maybe there was some weirdo in the park today. Maybe I shouldn’t have gone walking in the late afternoon.

I’d almost convinced myself I’d just imagined the voice, when it came again:

“Hey, you.”

A crackling, guttural voice. The crows bounced with appreciation.

I truly thought just then that the crows were talking to me, that they’d selected me for some strange purpose, and I suddenly saw that all around me the trees were mottled with them, watching and waiting.

The voice came a third time, “Hey, you.”

No, no, no, there’s no way a crow is talking, I told myself. And no way they’d say the same thing three times. By now I’d calmed myself a bit, and could tell it was a very small voice coming from where the crows had flown away moments before. I shoved my hands in my pockets and crossed the few meters to the clearing’s edge.

In the leaves there lay a dirty, stiff little teddy bear, pieces of stuffing sticking up from its chest. Its scratched brown eyes stared up at me, and a fourth time the robot voice croaked, “Hey, you.”

It was laughable, really, my mistake. I berated myself for being such a coward. But to tell you the truth, finding the toy didn’t shake the creepiness from my shoulders, or make me feel any more at ease rushing through the park and away from the crow flocks, till I was back on the city streets.

Animals do fascinate me, and I know crows are intelligent and curious. They’d been fixated on the talking robotic toy, picking at it, coveting it. It was either the sound of their voices, or perhaps a motion detector in the teddy bear’s eyes that had made it speak. The thought of the crows and the doll talking back and forth unnerved me.

* * *

Maybe a year or two later, I was out on a date with a woman.

Some of our mutual friends had set us up—the ineffable lesbian network of the inaka towns. It’s almost impossible to meet someone any other way. It’s the same people, cycling through like stew stirred in a stewpot. I don’t go to a bar to meet new people; I go there to hang out with someone I’ve already met.

Anyway, I’d met this woman named Tamura who had lived in Kanto for a while before moving back to the slower lifestyle down south, and she worked in the same city as me. I was taken by her poised, worldly ways; I’d visited Tokyo a few times just like anybody else, and I didn’t think there was anything special about it. But maybe you had to live there a while to let the juice percolate, I thought, because Tamura seemed like a quintessential cosmopolitan with her apartment full of art and movie posters and the glass beaded jewelry on her wrists and ankle.

We sat comfortably on the floor by the couch, sipping white wine, discussing our jobs. She was a social worker.

Tamura’s building looked out over a temple where a monk was putting out bowls of kibble and fish scraps for the stray cats, which was how my discomfort around animals came up.

“You don’t like them at all?” she asked. “Just the big ones, or all of them?”

“It’s not the size that makes a difference,” I said. “I went horseback riding as a kid once, and that wasn’t too bad. And zoos and aquariums aren’t terrible—just so long as the animals don’t look at me.”

“I always loved watching nature documentaries as a kid,” she said dreamily.

“Yeah, they are interesting. I like the science of it all… from afar.”

She was silent for a little while, and I worried, ah, I’ve gone and blown it. She’s probably a huge animal lover with five big dogs at her parents’ home and I’ve offended all of them.

But instead she said, “No, I feel a little uneasy around animals too.”

“Really?”

“I meet a lot of unfriendly ones for sure, going out to visit clients. Shiba Inu look cute, but get an unsocialized one and they’re the worst!” She pantomimed a bite with one hand and we chuckled. I’ve heard even the cutest Shiba can be real ankle-biters.

She calmed a little, and looked up at me through the dark fringe of her bangs.

“Do you want to hear a ghost story?”

A weird turn.

“Sure,” I said, raising my eyebrows.

A sip of wine.

“This is what happened to me. This is what I saw, or thought I saw:

“Almost all of my clients are elderly people. Especially since I moved back to Kyushu, so many people out here are old, and their kids have moved away north to the big cities. Like I did. And you get people who are so old and living alone, and sometimes their spouse dies and then they’re really alone. Or always were alone—no family, no kids, not even a niece or a nephew around to take care of them.

“So when I do my rounds, I check how they’re doing, if their houses are clean enough and their food hasn’t gone to roaches. See that their pension checks are arriving okay. Make sure the AC units work before it gets too hot or too cold. If they need something, I can connect them to a meal delivery service, or a ride service, or a good housekeeping company. Find programs for them at the community center, the usual.

“A little over a year ago, when I’d only just moved back, I got a real scare. I had a scheduled visit to this old man who lived in an apartment. An old mansion-building, but in a good part of town. His floor was near the top. I rode up in the elevator, and gave his door a knock.”

With a mischievous glint in her eye, Tamura rapped her knuckles on the floor.

“I went ahead and let myself into the genkan, calling, ‘Sorry to disturb you, sir! I’m the new social worker.’

“The building looked nice from the outside and from the hall, but the old man’s apartment was a disaster. It was dark and run-down and smelled awful. He must have been living there for decades—there were stacks of yellow newspaper on the shoebox, plastic bags of cans and bottles mounded up. He must have said no to a housekeeper, or couldn’t afford one, but I knew I’d have to write up some report about the state of things.”

Her nose wrinkled at the memory of it.

“I called again, ‘Sorry to disturb you!’

“I heard a faint voice from somewhere within. ‘Please, step inside,’ it said.

“I slipped out of my shoes and looked around for slippers. They were waiting on the genkan step, but were so worn out and stained I didn’t put my feet in them. ‘Sorry to disturb you,’ I said again, and I walked into the next room.

“The kitchen was even worse. All the lights were off, and I couldn’t find a switch that worked, but the sun was setting and the light through the window was more than enough—dirty dishes, trash, old food waste. Baby cockroaches skittering through the sink like it was a beach pier. And the smell! Rot and garbage, and worse—an ammonia smell. Cats. There was so much cat fur in the air, I didn’t even think I had an allergy but my nose started to itch. There must have been unclean litter boxes everywhere from the smell of it.”

“God, it sounds awful,” I interjected, drinking some wine—mindful that it resembled pee.

“It wasn’t the first time,” Tamura said. “I’ve seen clients with huge assortments of animals. A woman who kept her window open so the neighborhood strays had free access… anyway. I kept walking further in. I called, ‘Sir! I’m from the Ministry of Health. Sir, Mr. Yamamoto? I’ve come to see how you were doing, and to offer any assistance to help you get care.

“I heard the voice again: ‘Come in! I’m over here.’ It sounded like a weak old man’s voice.

“I thought, oh no, perhaps he’s bedridden or he’s fallen down. He must be, to let his house get to this state. I was making lists in my mind of all the things I’d have to do, all the calls I’d have to make. It didn’t look like he could live independently.

“I kept moving onward. I peeked into each room—the living room, spare room. Each was shadowy, and packed to the ceiling with junk. He must have been a hoarder, I thought. I’d seen terrible situations before, and this was one of the worst.

“Then I reached the final bedroom, where the door was open ajar.

“ ‘In here!’ called the voice.”

Tamura slowed to a stop, and leaned forward a little, almost imperceptibly. Her eyes locked on mine, and they were wide and dark.

“This is what I saw. I pushed open the door and walked into the room. The smell. It was awful. In here, the light was on. And in the yellow glow, I thought I saw a mound covered in a black blanket.

“Then I looked to the right—and I gasped. Ahh! It was the old man!”

I gasped too.

“He was dead. He had been dead for days, his skin was bloated and putrefying. And there was only half of him left. Below the waist, everything was chewed away.

“I looked to the left—and I saw it wasn’t a big blanket, not at all. I saw the head of an enormous cat, as large as a lion, chewing on some part of the old man. And its body was huge, and stretched round like a snake that had swallowed a pig whole. It looked like a couch covered in a blanket or something, that’s how monstrous this creature was. And it stopped, and rolled its eyes towards me, and I saw they were glittering and black like a shark’s, except for the silver ring of the under-eyelids.

“I screamed. And I ran out of there. My heart wouldn’t stop racing until I’d driven away and stopped on a busy street and leaned down on the steering wheel to catch my breath. I wouldn’t go back, not even when the police and paramedics went.”

“What happened?” I gasped. My hand was at my mouth, though I didn’t remember putting it there. “What did they find?”

“No monster cat,” Tamura said wryly. “They said they found the old man’s remains, and it looked like his pet cat had eaten part of him out of desperation. They thought I’d lost my nerve seeing something so horrible, and had dreamed the rest. It’s not that uncommon, actually. For the elderly to die at home and for us to find them, and sometimes for their pets to snack on them a little. Even something that loves you will turn on you, if it’s desperate enough.”

“That’s horrible. But you’re still sure what you saw?”

“Who knows. I still see it clearly in my mind’s eye, but I doubt it now myself,” Tamura said, finishing her glass. “It didn’t scare me away from social work. But I did take some time off to gather myself.”

She looked up at me again with mischievous eyes, and I wasn’t sure if all she’d told me was sincere or just theater.

“So now, I never look at animals quite the same, and I think I’ll probably never own a cat. I’d rather die alone.”

Kat Joplin (they/them) is a Vietnamese American writer and journalist based in Tokyo, Japan. Their work explores queer sexuality and gender, as well as themes of foreignness and belonging. They have written articles for platforms such as Gay Times and The Japan Times; have published creative pieces with The Wise Owl and The Examined Life Journal; and are contributing author to the upcoming book Planet Drag.

As a drag queen, they can be found performing throughout Japan under the stage name Le Horla.

Instagram: kat_dearu